Abstract

Stoichiometry is one of the foundational concepts in general chemistry, yet many students struggle to fully understand its underlying principles. In spite of repeated exposure in instructional settings, alternative conceptions about stoichiometric relationships, limiting reagents, and chemical equations persist, which often hinder student success and their progress in chemistry education. The aim of this study is to investigate some of conceptual difficulties and challenges students encounter in learning about stoichiometry and examine how these alternative conceptions affect students’ problem-solving abilities and confidence levels. Drawing upon data collected through Likert-type surveys and multiple-choice diagnostic questions administered to General Chemistry I students, the paper identifies specific areas of difficulties and confusion, interpreting coefficients versus subscripts and applying the mole concept in multi-step calculations. Data was collected through a questionnaire distributed to 193 science majors at The City College of New York. The findings show that while students demonstrate procedural fluency in tasks like balancing equations, their conceptual understanding remains superficial, especially when addressing limiting reagents or combustion analysis. The authors recommend that educators promote a conceptual rather than just procedural approach which can enhance student success and performance.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2604

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

Publication date: 01 Jan 2026

Article Views: 1964

Article Downloads: 413

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

The process of learning and understanding, especially in a course like chemistry, is a difficult process. Past studies have shown a great number of difficulties and have begun to identify causes that can explain why such conditions occur. Of these studies, many have been carried out in scientific topics such as physics and biology at roughly 70 and 20 percent. Chemistry is lagging and accounting for only 10 percent of studies in difficulties of scientific learning (Treagust et al., 2000). Of the studies done in chemistry education, researchers are largely focused on determining how students learn concepts, practices, and their thought processes (Tümay, 2016).

Perspectives like behaviorists and constructivists have influenced chemistry education and its research. Behaviorist ideas stem from the belief that there is no way to view the mind clearly, but it’s best to look at learning in terms of stimuli that impose on one’s senses and to over serve the response to such stimuli (Vygotsky, 2020). Behaviorist theories create the idea that knowledge has its own existence. It’s the job of the teacher to assist the student in finding knowledge and doing so by putting themselves in the students’ heads. This occurs by instructors providing stimuli and conditioning them for an appropriate response. Students, in essence, are just entities that are manipulated by teachers who receive information and respond with answers that are deemed acceptable (Herron & Nurrenbern, 1999).

Of the multiple constructivist models that have been developed (Lawson et al., 1989; Osborne & Freyberg, 1985), cooperative learning has been the most widely used (Sharan, 1985; Slavin, 2000; Slavin et al., 2003). Cooperative learning suggests learning activities to be centered around students in small groups working with one another to achieve a collective learning objective. Research on the efficacy of cooperative learning typically compares the results of student achievements of those who work in small groups with those who work individually (Herron & Nurrenbern, 1999). Cooperative learning and its effectiveness are linked to learning theories. Cooperative groups rely on working together to make progress in learning material (Johnson & Johnson, 1990).

Researchers credit several factors that are advantageous in the learning progress. The level and nature of cognitive processing arises when students try to describe a thought or comprehend the explanations of someone else assists them in creating and using elaborative metacognitive strategies and higher-level reasoning methods more often than they would do so learning independently of others. Another aspect is teachers making students become more responsible for learning and collectively adjusting their attention when in the role of a mentor, facilitator, or helper, rather than being a collector of information (Sharan & Hertz-Lazarowitz, 1980). Some additional factors that have been discussed but not investigated thoroughly that could possibly contribute to increased learning in a cooperative manner are rewards structures that have students and peers recognizing one another, academia task structures and the time consumed on sharing ideas to the learning objective (Herron & Nurrenbern, 1999).

Whilst a large component of chemistry education research has been focused on how students learn and the thought processes behind it, the learning difficulties that they face has been a major concern in the community (Teo et al., 2014). While the ideas and learning methods that branch from ideas like constructivism provide a hypothetical structure as to how students can learn and what methods are useful, productive idea-specific frameworks are needed to understand why learning difficulties still occur. The focus of chemistry education and how students learn should shift its focus on identifying its difficulties and addressing them in a manner that is unique and significant that allows us to understand the reasons behind the problems students face (Erduran, 2007; Erduran & Scerri, 2002; Scerri, 2001; Shulman, 1987; Tümay, 2016).

Chemistry as a class contains ideas that are deep and abstract in content, making it difficult to understand. How a student learns material can affect their class performance and the methods they use to try to process that information (Montenegro & Cascolan, 2020). Students have their own stated learning styles and preferences that they identify as from the following list: Avoidant, Collaborative, Competitive, Dependent, Independent, and Participant. Avoidant learners find themselves too overwhelmed by learning situations and become less interested in the class because of it. Collaborative learners prefer to work with their peers, including teachers as well, to learn by means of sharing ideas with one another. Competitive learners find themselves competing with their peers in their class scores and prefer to have recognition of their own achievements, no one else. Dependent learners show enough interest to learn what is required, putting in a bare minimum attempt at learning. Independent learners prefer to work and think on their own, with the utmost confidence in their abilities. Lastly, participant learners find themselves willing to help and do whatever necessary to learn (Elban, 2018). Although factors as such can affect a student’s learning ability and their conceptualizations, they don’t single handedly give us a clear and concise understanding as to why misconceptions develop (Tümay, 2016).

A misconception or alternative conception is often referred to as an idea, sense, or thought that it is not built on a scientific understanding. Incorrect lack of understanding leads to alternative conceptions becoming indifferent to change (Nicoll, 2001; Nicoll & Francisco, 2001; Nicoll et al., 2001). When a student is presented with new information, the process of learning is directed by its preconceptions, that selectively directs it to parts of information they have prior knowledge in. The brain then acts on the selected information and creates its own interpretations based on this previous knowledge. Before any new information is retained, it must undergo comparisons to prior knowledge (Nakhleh, 1992). Research has shown that students who carry alternative conceptions of scientific concepts to their class hinder their ability to learn concepts accurately (Taber, 2000). Researchers have highlighted the importance of instructors to help mitigate the possibility of student alternative conceptions when preparing material to present in teaching (Smith III et al., 2009; Taber, 2008). To assist instructors in being aware of the misconceptions in a chemistry course, misconception teaching strategies specific to the chemistry course should be specially created for instructors before they teach (Naah, 2015).

Research investigating student alternative conceptions in recent years has discovered acid-based concepts as one that students tend to struggle with greatly, leading to the identification of fifteen known alternative conceptions. Concepts such as acid- base equilibria, have five discovered alternative conceptions alone: more of hydrogen gas is moved from a strong acid because strong acids contain more hydrogen bonds than a weak acid; all acids are strong acids; neutralizations result in entire solutions becoming neutralized; the pH of stronger acid are greater than that of weak acids; salts cannot have hydronium or hydroxide ions because salts lack hydrogen or hydrogen groups such as hydroxyls (Griffiths, 1994).

Looking at neutralization alone, the term is used as an inducer in a reaction, acting upon a component of a reaction. Students apply the term to the entirety of a reaction, assuming that when something undergoes neutralization, the entire product is then neutralized (Schmidt, 1991). Some concepts have one idea that tends to be the misconception that most students are making and struggling to understand while others have multiple misconceptions of one main idea that branches into incorrect concepts that are different from each other. For instance, another study into acid base concepts found the misconception of hydrogen gas and its bonds to be greater in a strong acid versus a weak one to be prevalent in their design. However, ideas such as pH and weak acids had different misconceptions from the previous stated research. Students in this group believed pH is a measure of acidity alone, and not basicity. They also believed weak acids cannot accomplish as well as strong acids (Garnett et al., 1995). The different avenues that students can go on when attempting to understand a concept result in different ideas that are still incorrect. A potential cause for this lack of understanding and multiple misunderstandings, stems from textbook models that leaves readers regularly confused (Carr, 1984).

Modeling of chemical concepts and its importance has long drawn the attention of chemists (Alcock, 1979; Tomasi, 1988). Models are structures and schemes that relate to real objects, events or periods of events that can be explained (National Research Council, 1996, p. 117). How students interpret models will ultimately be their understanding of what concept/concepts the model is trying to visualize and display for the student. How they obtain knowledge and understand conceptual information is only one component of the learning process of correctly conceptualizing ideas. Students need to learn the how’s and why’s behind the construction of the model. They also need to understand how these models have been used in chemistry class. Chemical models have been represented to students usually as final versions of representation of a concept when it should be a tentative structure (Grosslight et al., 1991; Weck, 1995). In traditional teaching and learning strategies that explore the development and modification of certain ideas, chemical models are not focused enough on. Chemists and textbooks do not clearly differentiate between chemical models and what they are but choose to represent them as hybrid models. Those hybrid models are displayed in a way that one can make sense of its physical and chemical components why something is the way it is (Kousathana et al., 2005).

Alternative conceptions occur in all levels of undergraduate chemistry. Research has found that misconceptions can develop in future courses on concepts previously mastered. Acid and base chemistry in relation to Bronsted and Lowry theory doesn’t cause problems. But acid and base chemistry under the Lewis generalization which integrates concepts such as electrophilicity, nucleophilicity and acid-base chemistry, triggers a plethora of struggles and alternative conceptions (Zoller, 1990). Alternative conceptions are not only limited to challenging concepts. Research has also found that when students learn about total ionic equations, they are accustomed to “removing” spectator ions when deriving the net ionic equation. However, the concept of “removing” is incorrect, as matter is not being removed or replaced. It is simply being disregarded in terms of a net ionic equation, a notion that not all students are aware of (Kelly et al., 2009).

Within the fields of undergraduate chemistry, students have found chemical equilibrium and stoichiometry to be some of the most difficult concepts to grasp due to its abstractness (Ben-Zvi et al., 1986; Hackling & Garnett, 1985). Even students who can successfully solve stoichiometric problems demonstrate a weak understanding of submicroscopic reactions and the polyatomic ions that are involved (Hinton & Nakhleh, 1999). Previous studies have shown that students struggle to accurately conceptualize stoichiometry because of overstressing the importance of the final answer. Rather than learning and understanding the reasons as to why you solve a stoichiometric problem the way you do, an emphasis is placed on how to get to the result (Nurrenbern & Pickering, 1987).

However, all students are not hindered by solving for a final answer. A plethora of stoichiometric misconceptions stem from issues of other chemical sub concepts that are necessary skills to solve stoichiometric problems. Researchers have found that students who have limited skill in mathematics contribute towards their difficulties when faced with the challenge of stoichiometric problems (Dahsah & Coll, 2008). Other studies have shown that students tend to prioritize and use formulas exclusively when solving stoichiometric problems, without being able to conceptually explain the methods they are using (Fach et al., 2007). Even more so, multiple studies have found that misconceptions of the mole concept led to difficulties in approaching and correctly solving problems (Chandrasegaran et al., 2009; Dahsah & Coll, 2007; Gauchon & Meheut, 2007).

Mole concept is one of the most important aspects of stoichiometry that students must have a thorough understanding of (Kolb, 1978). It’s needed to understand the relationships between compounds and their mass or atoms. Research finds, however, that students are all over the place with their understanding of the concepts. Some students believe the ratio of moles to atomic mass units of a compound is always a one-to-one ratio. They’re unable to differentiate moles of a compound with the mass of a compound and the atomic mass of a compound. Furthermore, they believe the number of moles of a given compound in a problem is the same in any reaction that can take place (Cervellati et al., 1982; Staver & Lumpe, 1993). Other students fail to understand balanced equations and how to identify them. Because of that deficiency, they assume that the ratio of reactants and products are again, always one-to-one (Huddle & Pillay, 1996). Even more so, students believe the limiting reagent is whatever aspect of the reaction that has the lowest coefficient (BouJaoude & Barakat, 2000; Krishnan & Howe, 1994).

An unsound foundation in stoichiometric concepts can lead to difficulties throughout chemistry courses during undergraduate studies. The overall understanding of the strategies required to solve stoichiometric problems are rooted into the entirety of general chemistry. For instance, gas laws act upon the conceptual knowledge of the relationships between pressure and volume, pressure, and temperature, etc. Furthermore, it requires a deep understanding of moles, molecules, and the manner in which they are calculated. (Atkins, 1999; Cooper et al., 2017; Holme & Murphy, 2012).

METHODS

To develop effective approaches to overcome alternative conceptions, a well-prepared analysis of the subproblems is necessary to gain comprehension in the successes and mistakes students encounter when solving stoichiometric problems (Gulacar et al., 2020). A two-tier concept inventory exploring stoichiometric questions can measure the knowledge through reasoning. While a one-tier question measures content knowledge directly by an answer to a question, two-tier questions require an answer and a specification as to how that answer was determined (Adams & Wieman, 2010; Treagust, 1988).

The sample equations provided to the students in the survey are as follows:

A student was asked to balance the following equation:

| \[{Ca}_{3}\left( PO_{4} \right)_{2} + SiO_{2} \rightarrow {CaSiO}_{3} + P_{4}O_{10}\] | (1) |

|---|

The student’s answer was as follows:

| \[{Ca}_{3}\left( PO_{4} \right)_{4} + 3\ SiO_{2} \rightarrow {3\ CaSiO}_{3} + P_{4}O_{13}\] | (2) |

|---|

The study took place at the City College of New York, a commuter, public, and minority serving institute. The participants’ population is as diverse as the institution and are students who are enrolled in General Chemistry I courses. The data was collected from 193 participants with a survey that was approved by the Internal Review Board (IRB) and in accordance to the college protocols.

To explore student comprehension and difficulties of stoichiometry, a study was designed to answer three research questions:

RQ1 What are some of the alternative conceptions and challenges students face with learning about stoichiometry?

RQ2 How well do students retain a conceptual understanding of stoichiometry throughout the course of a semester?

RQ3 Can students explain their reasoning as to how and why they use the methods that they use for problem-solving?

According to two experts who examined the survey, the questions appropriately capture the investigation into learning difficulties and challenges students face in learning about stoichiometry and how it impacts performance. Using the test-retest method, the reliability coefficient was determined to be 0.87. A single factor ANOVA was performed on the Likert-type questions, and the results showed a substantial correlation between the variables and strong evidence against the null hypothesis (p<.001 and p-value <0.05).

For Likert-type questions, answers were converted to numerical values depending on the category of the response: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neutral, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly agree. Averages were calculated based on student response for these types of questions. These types of questions included those addressing topics such as students’ strategies to approaching stoichiometry related problems difficulties and challenges they face in solving these problems. Responses to open-ended questions were compiled, coded and converted to graphs on bar graphs using the percent of students responses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the answers collected from the Likert-type questions shown in Table 1, most students felt confident in their ability to assign coefficients when solving balancing equation problems, and they felt that they have a good understanding of what coefficients represent in a chemical equation. Students felt less confident in their understanding of the effect of limiting and/or excess reagents, as well as of their ability to determine the limiting reagent in a reaction. They also indicated that they had difficulty determining what the limiting reagent was on the problem they were asked to solve. Furthermore, students didn’t feel confident that they had retained their knowledge from their General Chemistry I course, but many indicated little to no difficulty applying their knowledge of balancing equations to the reaction they were given, and they were very confident about their ability of converting between units of mass and moles. Lastly, very few students felt confident solving a combustion analysis problem.

Table 1. Likert-type questions and average answers from respondents

|

These results are supported by research showing students often know definitions of concepts while being unable to see how these concepts connect (Koponen & Nousiainen, 2018). It is no wonder that students struggle with conceptualizing and applying the principles of limiting reagents and stoichiometry in practical contexts, a phenomenon that may be exacerbated by the lack of empirical evidence supporting effective teaching methods of stoichiometry, making it difficult to teach properly (Abban-Acquah & Ackah, 2025).

Additionally, while students may grasp the mechanical process of balancing equations, they frequently encounter difficulties when tasked with understanding the quantitative relationships in chemical reactions, such as the concept of the limiting reagent. Students usually know chemical equations had to be applied but have difficulty properly doing so when ratios of substances had to be considered (Papaphotis & Tsaparlis, 2008).

Retention of knowledge from earlier chemistry courses can also be inconsistent, particularly in areas that require a deep understanding of abstract concepts. This may be because many students are often taught a skill without being taught the reasons for learning it, which has been shown to hinder the learning process (Cooper et al., 2010; Owens & Tanner, 2017).

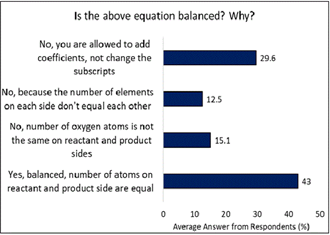

While students felt confident in their ability to assign coefficients in balancing equation problems, only 29.6% of students were able to correctly identify whether the equation provided was balanced and explain why or why not as shown in Table 2, showing that many students possess confidence that was not backed by their actual ability to solve a problem. This indicates a deficiency in their metacognitive abilities, lacking the knowledge necessary to self-assess their own learning. This bias about their own abilities is likely due to misconceptions in the topics they needed to solve the problem they were assigned. By having misconceptions about topics that are of importance for the problem-solving process, students are likely to believe they are properly applying their skills and do not realize where they may be making mistakes.

Table 2. Likert-type questions and average answers from respondents

|

This cognitive bias is known as the Dunning–Kruger effect, a phenomenon where people often overestimate their understanding and performance, and where the less a person knows about a concept, the more likely they are to overestimate their ability due to their incapacity to see the gaps in their knowledge (Dunning et al., 2003). Alternative conceptions in foundational concepts, such as stoichiometry and chemical equations, further exacerbate this issue, as students may apply incorrect principles without recognizing their errors (Mulford & Robinson, 2002). The lack of metacognitive skills, including the ability to accurately self-assess and adjust learning strategies, contributes to persistent misconceptions and overconfidence (Tanner, 2017).

As shown in Figure 1, the correct answer to the question asking if the equation was balanced, was that it was not, and the reason is that while one is allowed to add coefficients, changing subscripts is not permitted. However, only 29.6% of students were able to correctly identify this. The most common mistake when answering this question, made by 43% of students, was that the equation was indeed balanced because the number of atoms on the reactant side and product side were equal. On the other hand, 27.6% of students correctly responded that the equation was not balanced but failed to correctly identify why. Of these students, 15.1% explained that the reason it was not balanced was due to the number of oxygen atoms not being the same on the reactant and product sides, while 12.5% said that the number of elements on each side was different. The results from Figure 1 show a trend of more than 70% of students provided an incorrect answer to the questions asked with varying incorrect reasoning.

These results highlight common misconceptions in chemical education, particularly regarding the distinction between coefficients and subscripts in balancing equations (Hamerská et al., 2024). Research indicates that students often struggle with the procedural and conceptual understanding required for balancing chemical equations, frequently confusing the roles of coefficients and subscripts (Martin, 2025). Relying on memorization of algorithms over conceptual understanding and scientific reasoning, leading to confusion and incorrect application (Cracolice et al., 2008; Nyachwaya et al., 2014). These misconceptions can lead to errors in determining whether an equation is balanced and why, as evidenced by the incorrect explanations provided by many students. Effective instruction needs to address these specific areas of misunderstanding to improve student comprehension and problem-solving skills such as active and engaged learning, making connections between the different levels of representations, scaffolding, and development of problem-solving skills (Cracolice et al., 2008; Nyachwaya et al., 2014; Taber et al., 2002).

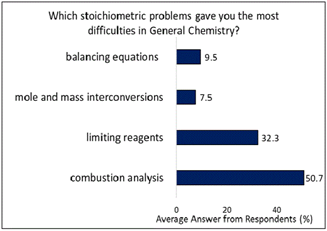

Consistent with the answers from Table 1, Figure 2 shows students expressed that of the stoichiometric problems from General Chemistry, the problems they had most difficulty with were combustion analysis problems, followed by limiting reagents, and to a much lesser extent balancing equations followed by converting between units of mass and moles.

Confidence in performing unit conversions between mass and moles likely stems from the repetitive practice of these calculations in coursework, which tends to be more straightforward compared to solving more complex problems like combustion analysis, which involves multiple steps and a robust understanding of chemical principles. One of the reasons why students have been found to struggle with combustion analysis is that they were performing based on memorization rather than deep understanding of the material, leading to struggles applying rules to a variety of scenarios (Holme et al., 2015; Robertson & Shaffer, 2014).

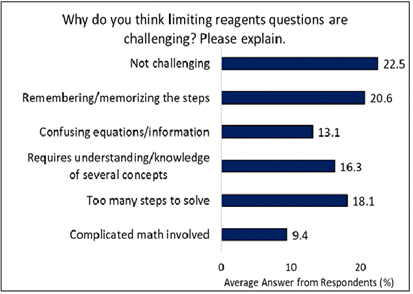

As shown in Figure 3, when asked why they thought that limiting reagent questions were challenging, the most common answer was that they were not challenging (22.5%). Of the students that did find these questions challenging, 20.6% attributed this to having difficulty memorizing/ remembering the steps required to solve the problem. 18.1% of the students attributed the difficulty to the number of steps involved in solving the problems. 16.3% indicated that their difficulty was due to such problems requiring knowledge and understanding of several concepts. 13.1% said that the problems were difficult because the equations and/or information given was confusing which could be related to lack of well-developed understanding of chemical equations, stoichiometry, and calculations related to these problems. Lastly, 9.4% said that they were difficult because they involved complicated math. The data in the figure shows that majority of students (77.5%) find limiting reagents problems to be challenging and they attribute that to the difficulties that were just discussed.

Research supports these findings, showing that students often struggle with limiting reagent problems due to the complexity and multi-step nature of the problems, which demand a solid understanding of stoichiometry and the ability to integrate various concepts, rather than relying on memorization of procedures and steps (Cracolice et al., 2008; Holme et al., 2015).

It seems that the reasons for why students found the problems difficult are related to each other, with the underlying cause often relating to student’s use of memorization over conceptual understanding (Heber et al., 2023). Students who felt it was difficult because it was a lot to memorize failed to realize that if they understood why each step of the process happens, they would be able to apply this knowledge to any new problem without requiring memorization of the steps, as there would be a logical step by step process that would follow. Likewise, the students who found the difficulty to be related to the number of steps involved were likely operating under the misconception that they had to memorize steps, as understanding how the different parts of the problem come together would likely make it easier to move from one step to the next (Roselizawati et al., 2014).

Students who felt their difficulty solving problems was due to the problem-solving process requiring knowledge of several concepts were likely correctly identifying that solving these problems required the understanding of why each step is taken rather than memorizing the steps, but we’re having difficulty putting the concepts together, which could be due to gaps in knowledge and/or unidentified misconceptions in one or more of the concepts involved. Misconceptions in any of these concepts would make it difficult to properly solve the problem, as it is not just many steps to keep track of but multiple concepts and intricacies. The difficulty due to memorization is a misconception about what the best way to solve a problem is, placing importance on memorization instead of understanding the process can lead to many mistakes that could easily be avoided if concepts were understood. Furthermore, applying the knowledge to new problems would be easier in new situations if the steps involved and why they are done are understood rather than memorized (Roselizawati et al., 2014).

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the complexity of stoichiometry as a fundamental and yet challenging concept in general chemistry education. The research study shows that students face many challenges when learning about stoichiometry related problems which include complicated mathematics, lack of conceptual understanding, balancing equation, mole and mass interconversions, confusion about equations, the number of steps involved, and reliance on memorization. Aside from demonstrating procedural skills, students often show gaps in conceptual understanding, particularly in cases when distinguishing between coefficients and subscripts, applying the mole concept, and identifying limiting reagents. The data shows that misconceptions persist across various learning stages and are influenced by cognitive biases such as the Dunning–Kruger effect and a reliance on memorization over comprehension and conceptual understanding.

A key finding of the experiment is that while students feel confident in performing routine calculations, their struggles with abstract concepts, like combustion analysis and limiting reagents, show the need for more effective instructional approaches. Cooperative learning, conceptual modeling, and metacognitive strategies emerged as essential methods to connect the gap between procedural knowledge and deeper conceptual understanding. Combining these strategies into chemistry curricula can help students develop a more comprehensive understanding of stoichiometry which would enable them to better navigate complex problem-solving scenarios. Future research should focus on designing educational interventions that clearly address common misconceptions, making sure to encourage both critical thinking and metacognitive awareness. Addressing gaps students have in learning about chemistry concepts requires targeted educational interventions that promote metacognitive awareness and correction of misunderstandings (Schraw et al., 2006; Tanner, 2017). By promoting a conceptual rather than just procedural approach, educators can improve student success in chemistry and other related fields.

Author contributions: IIS: conceptualization, supervision; HK: investigation, writing - original draft; AI: writing - review and editing. All authors have agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: No funding source is reported for this study.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that the study was approved by the Human Research Protection Program of The City College of the City University of New York (Approval Code: 2023-0111-CCNY; Approval Date: February 27, 2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

AI statement: The authors stated that AI was not used for this research study.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Abban-Acquah, F., & Ackah, J. E. (2025). First principle approach and students’ determination of limiting reagents in chemical stoichiometry. Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 2(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.12973/jmste.2.1.1

- Adams, W. K., & Wieman, C. E. (2010). Development and validation of instruments to measure learning of expert‐like thinking. International Journal of Science Education, 33(9), 1289-1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.512369

- Alcock, J. W. (1979). Chemistry through models (Suckling, Colin J.; Suckling, Keith E.; Suckling, Charles W.). Journal of Chemical Education, 56(8), Article A259. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed056pa259.2

- Atkins, P. (1999). Chemistry: The great ideas. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 71(6), 927-929. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199971060927

- Ben-Zvi, R., Eylon, B.-S., & Silberstein, J. (1986). Theories, principles and laws. Education in Chemistry, 25, 89-92.

- BouJaoude, S., & Barakat, H. (2000). Secondary school students’ difficulties with stoichiometry. The School Science Review, 81, 91-98.

- Carr, M. (1984). Model confusion in chemistry. Research in Science Education, 14(1), 97-103. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02356795

- Cervellati, R., Montuschi, A., Perugini, D., Grimellini-Tomasini, N., & Balandi, B. P. (1982). Investigation of secondary school students’ understanding of the mole concept in Italy. Journal of Chemical Education, 59(10), Article 852. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed059p852

- Chandrasegaran, A. L., Treagust, D. F., Waldrip, B. G., & Chandrasegaran, A. (2009). Students’ dilemmas in reaction stoichiometry problem solving: Deducing the limiting reagent in chemical reactions. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 10(1), 14-23. https://doi.org/10.1039/b901456j

- Cooper, M. M., Grove, N., Underwood, S. M., & Klymkowsky, M. W. (2010). Lost in Lewis structures: An investigation of student difficulties in developing representational competence. Journal of Chemical Education, 87(8), 869-874. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed900004y

- Cooper, M. M., Posey, L. A., & Underwood, S. M. (2017). Core ideas and topics: Building up or drilling down? Journal of Chemical Education, 94(5), 541-548. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00900

- Cracolice, M. S., Deming, J. C., & Ehlert, B. (2008). Concept learning versus problem solving: A cognitive difference. Journal of Chemical Education, 85(6), Article 873. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed085p873

- Dahsah, C., & Coll, R. K. (2007). Thai grade 10 and 11 students’ conceptual understanding and ability to solve stoichiometry problems. Research in Science & Technological Education, 25(2), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635140701250808

- Dahsah, C., & Coll, R. K. (2008). Thai grade 10 and 11 students’ understanding of stoichiometry and related concepts. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 6(3), 573-600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-007-9072-0

- Dunning, D., Johnson, K., Ehrlinger, J., & Kruger, J. (2003). Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 83-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01235

- Elban, M. (2018). Learning styles as the predictor of academic success of the pre-service history teachers. European Journal of Educational Research, 7(3), 659-665. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.7.3.659

- Erduran, S. (2007). Breaking the law: Promoting domain-specificity in chemical education in the context of arguing about the Periodic Law. Foundations of Chemistry, 9(3), 247-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10698-007-9036-z

- Erduran, S., & Scerri, E. (2002). The nature of chemical knowledge and chemical education. Chemical Education: Towards Research-Based Practice (pp. 7-27). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47977-x_1

- Fach, M., de Boer, T., & Parchmann, I. (2007). Results of an interview study as basis for the development of stepped supporting tools for stoichiometric problems. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 8(1), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.1039/b6rp90017h

- Garnett, P. J., Garnett, P. J., & Hackling, M. W. (1995). Students’ alternative conceptions in chemistry: A review of research and implications for teaching and learning. Studies in Science Education, 25(1), 69-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057269508560050

- Gauchon, L., & Méheut, M. (2007). Learning about stoichiometry: From students’ preconceptions to the concept of limiting reactant. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 8(4), 362-375. https://doi.org/10.1039/b7rp90012k

- Griffiths, A. K. (1994). A critical analysis and synthesis of research on students’ chemistry misconceptions. In H. J. Schmidt (Ed.), Problem solving and misconceptions in chemistry and physics (pp.70-79). ICASE

- Grosslight, L., Unger, C., Jay, E., & Smith, C. L. (1991). Understanding models and their use in science: Conceptions of middle and high school students and experts. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 28(9), 799-822. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660280907

- Gulacar, O., Cox, C., Tribble, E., Rothbart, N., & Cohen-Sandler, R. (2020). Investigation of the correlation between college students’ success with stoichiometry subproblems and metacognitive awareness. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 98(11), 676-682. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjc-2019-0384

- Hackling, M. W., & Garnett, P. J. (1985). Misconceptions of chemical equilibrium. European Journal of Science Education, 7(2), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140528850070211

- Hamerská, L., Matěcha, T., Tóthová, M., & Rusek, M. (2024). Between symbols and particles: Investigating the complexity of learning chemical equations. Education Sciences, 14(6), Article 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060570

- Heber, S., Grasl, M. C., & Volf, I. (2023), A successful intervention to improve conceptual knowledge of medical students who rely on memorization of disclosed items. Frontiers in Physiology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1258149

- Herron, J. D., & Nurrenbern, S. C. (1999). Chemical education research: Improving chemistry learning. Journal of Chemical Education, 76(10), Article 1353. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed076p1353

- Hinton, M. E., & Nakhleh, M. B. (1999). Students’ microscopic, macroscopic, and symbolic representations of chemical reactions. The Chemical Educator, 4(5), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00897990325a

- Holme, T. A., Luxford, C. J., & Brandriet, A. (2015). Defining conceptual understanding in general chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(9), 1477-1483. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00218

- Holme, T., & Murphy, K. (2012). The ACS exams institute undergraduate chemistry anchoring concepts content map I: General chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 89(6), 721-723. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed300050q

- Huddle, P. A., & Pillay, A. E. (1996). An in-depth study of misconceptions in stoichiometry and chemical equilibrium at a South African university. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33(1), 65-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-2736(199601)33:1<65::aid-tea4>3.0.co;2-n

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1990). Cooperative learning and achievement. In S. Sharan (Ed.), Cooperative learning: Theory and research (pp. 23-27). New York: Praeger.

- Kelly, R. M., Barrera, J. H., & Mohamed, S. C. (2009). An analysis of undergraduate general chemistry students’ misconceptions of the submicroscopic level of precipitation reactions. Journal of Chemical Education, 87(1), 113-118. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed800011a

- Kolb, D. (1978). The mole. Journal of Chemical Education, 55(11), Article 728. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed055p728

- Koponen, I. T., & Nousiainen, M. (2018). Concept networks of students’ knowledge of relationships between physics concepts: Finding key concepts and their epistemic support. Applied Network Science 3, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-018-0072-5

- Kousathana, M., Demerouti, M., & Tsaparlis, G. (2005). Instructional misconceptions in acid-base equilibria: An analysis from a history and philosophy of Science Perspective. Science & Education, 14(2), 173-193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-005-5719-9

- Krishnan, S. R., & Howe, A. C. (1994). The mole concept: Developing an instrument to assess conceptual understanding. Journal of Chemical Education, 71(8), Article 653. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed071p653

- Lawson, A. E., Abraham, M. R., & Renner, J. W. (1989). A theory of instruction: Using the learning cycle to teach science concepts and thinking skills. Kansas State University. National Association for Research and Science Teaching.

- Martin, R. (2025). Unlocking chemistry calculation proficiency: Uncovering student struggles and flipped classroom benefits. Chemistry Teacher International, 7(1), 121-140. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2024-0054

- Montenegro, M. B., & Cascolan, D. H. M. S. (2020). Learning styles and difficulties of college students in chemistry. ASEAN Journal of Basic and Higher Education, 1(1). https://paressu.org/online/index.php/aseanjbh/article/view/177

- Mulford, D. R., & Robinson, W. R. (2002). An inventory for alternate conceptions among first-semester general chemistry students. Journal of Chemical Education, 79(6), Article 739. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed079p739

- Naah, B. (2015). Enhancing preservice teachers’ understanding of students’ misconceptions in learning chemistry. Journal of College Science Teaching, 45(2), 41-47. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/jcst15_045_02_41

- Nakhleh, M. B. (1992). Why some students don’t learn chemistry: Chemical misconceptions. Journal of Chemical Education, 69(3), Article 191. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed069p191

- National Research Council. (1996). National science educational standards. National Academy Press.

- Nicoll, G. (2001). A report of undergraduates’ bonding misconceptions. International Journal of Science Education, 23(7), 707-730. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690010025012

- Nicoll, G., & Francisco, J. S. (2001). An investigation of the factors influencing student performance in physical chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 78(1), Article 99. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed078p99

- Nicoll, G., Francisco, J. S., & Nakhleh, M. (2001). An investigation of the value of using concept maps in general chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 78(8), Article 1111. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed078p1111

- Nurrenbern, S. C., & Pickering, M. (1987). Concept learning versus problem solving: Is there a difference? Journal of Chemical Education, 64(6), Article 508. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed064p508

- Nyachwaya, J. M., Warfa, A.-R. M., Roehrig, G. H., & Schneider, J. L. (2014). College chemistry students’ use of memorized algorithms in chemical reactions. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(1), 81-93. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3rp00114h

- Osborne, R., & Freyberg, P. (1985). Learning in science: The implications of children’s science. Heinemann.

- Owens, M. T., & Tanner, K. D. (2017). Teaching as brain changing: Exploring connections between neuroscience and innovative teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-01-0005

- Papaphotis, G., & Tsaparlis, G. (2008). Conceptual versus algorithmic learning in high school chemistry: The case of basic quantum chemical concepts. Part 1. Statistical analysis of a quantitative study. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 9(4), 323-331. https://doi.org/10.1039/b818468m

- Robertson, A. D., & Shaffer, P. S. (2014). “Combustion always produces carbon dioxide and water”: A discussion of university chemistry students’ use of rules in place of principles. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(4), 763-776. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00089g

- Roselizawati, H. J. H., Sarwadi, H., & Shahrill, M. (2014). Understanding students' mathematical errors and misconceptions: The case of year 11 repeating students. Mathematics Education Trends and Research, 1-10.

- Scerri, E. R. (2001). The new philosophy of chemistry and its relevance to chemical education. Chemistry Education Research Practice, 2(2), 165-170. https://doi.org/10.1039/b1rp90016a

- Schmidt, H.-J. (1991). A label as a hidden persuader: Chemists’ neutralization concept. International Journal of Science Education, 13(4), 459-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069910130409

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education, 36(1-2), 111-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

- Sharan, S. (1985). Learning to cooperate: Cooperating to learn. Plenum.

- Sharan, S., & Hertz-Lazarowitz, R. (1980). A group-investigation method of cooperative learning in the classroom. In S. Sharan, P. Hare, C. Webb, & R. Hertz-Lazarowitz (Eds.), Cooperation in education. Brigham Young Univ. Press.

- Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Slavin, R. E. (2000). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice. Allyn and Bacon.

- Slavin, R. E., Hurley, E. A., & Chamberlain, A. (2003). Cooperative learning and achievement: Theory and research. Handbook of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0709

- Smith III, J. P., diSessa, A. A., & Roschelle, J. (2009). Misconceptions reconceived: A constructivist analysis of knowledge in transition. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3(2), 115-163. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0302_1

- Staver, J. R., & Lumpe, A. T. (1993). A content analysis of the presentation of the mole concept in chemistry textbooks. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 30(4), 321-337. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660300402

- Taber, K. S. (2000). Multiple frameworks? Evidence of manifold conceptions in individual cognitive structure. International Journal of Science Education, 22(4), 399-417. https://doi.org/10.1080/095006900289813

- Taber, K. S. (2008). Exploring conceptual integration in student thinking: Evidence from a case study. International Journal of Science Education, 30(14), 1915-1943. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701589404

- Taber, K., Osborne, C., & Pack, M. (2002). Chemical misconceptions: Prevention, diagnosis and cure (Volume 1): Theoretical background. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Tanner, K. D. (2017). Promoting student metacognition. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(2), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033

- Teo, T. W., Goh, M. T., & Yeo, L. W. (2014). Chemistry education research trends: 2004-2013. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 15(4), 470-487. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00104d

- Tomasi, J. (1988). Models and modeling in theoretical chemistry. Journal of Molecular Structure-Theochem, 179, 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-1280(88)80128-3

- Treagust, D. F. (1988). Development and use of diagnostic tests to evaluate students’ misconceptions in science. International Journal of Science Education, 10(2), 159-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069880100204

- Treagust, D. F., Nieswandt, M., & Duit, R. (2000). Sources of students’ difficulties in learning Chemistry. Educación Química, 11(2), 228-235. https://doi.org/10.22201/fq.18708404e.2000.2.66458

- Tümay, H. (2016). Reconsidering learning difficulties and misconceptions in chemistry: Emergence in chemistry and its implications for chemical education. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 17(2), 229-245. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6rp00008h

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2020). Educational psychology. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273070

- Weck, M. A. (1995). Are today’s models tomorrow’s misconceptions? In Proceedings of the Third International History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (Vol. 2, pp. 1286-1294). University of Minnesota.

- Zoller, U. (1990). Students’ misunderstandings and misconceptions in college freshman chemistry (general and organic). Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27(10), 1053-1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660271011

How to cite this article

APA

Salame, I. I., Kanishka, H., & Ishak, A. (2026). Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

Vancouver

Salame II, Kanishka H, Ishak A. Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1):e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

AMA

Salame II, Kanishka H, Ishak A. Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1), e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

Chicago

Salame, Issa I., Haroon Kanishka, and Antonuos Ishak. "Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 1 (2026): e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

Harvard

Salame, I. I., Kanishka, H., and Ishak, A. (2026). Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

MLA

Salame, Issa I. et al. "Examining challenges and difficulties students face in learning about stoichiometry in general chemistry courses". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2026, e2604. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17701

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)