Abstract

Currently, the demand for STEM workers has encouraged education to focus on the orientation of STEM careers for students, especially raising the STEM career interest of students in the learning process. To this purpose, the evaluation activities in high schools not only provide information about the level of student capacity development but also need to provide information to help students orient their careers in the future. Based on this, a sample survey of 597 high school students was used to conduct the study. It used the Social Occupational Cognitive Theory (SCCT) to examine the influence of students’ STEM learning outcomes as evaluated by instructors and their assessments of their STEM abilities. To evaluate the effectiveness of the suggested theoretical model, this study uses the partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM). The research results show that STEM self-efficacy significantly impacts STEM career interests. Meanwhile, the results of the student’s assessment through the score of STEM subjects do not directly affect the student’s interest in a STEM career but are only indirectly affected via the mediating role of STEM self-efficacy, albeit with weak effect strength. The results are not much influenced by the gender and the type of school students study.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2605

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

Publication date: 20 Jan 2026

Article Views: 511

Article Downloads: 611

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

Assessment in Education

Assessment is a fundamental aspect of educational models (Elmore, 2019; Looney, 2009; Lucas, 2021). The organization of assessment activities depends on the perspective adopted, either focusing on knowledge and skills or capacity development. When assessment is geared towards memorization and reproduction of knowledge, it is often conducted by teachers solely to determine achievement levels and rankings (Elmore, 2019). However, if the approach is towards developing learner capacity, assessment takes on three characteristics: assessment for learning, assessment as learning, and assessment of learning results. This approach allows students to self-reflect and adjust their understanding, beliefs, and actions to align with their interests and societal requirements (Elmore, 2019). High school assessment should comprise both teacher-led and self-assessment activities, enabling students to monitor their capacity development process. Self-assessment fosters self-awareness, helping students understand the impact of their behavior on others and adjust accordingly (McMillan & Hearn, 2008; Spiller, 2012; Zulkosky, 2009). This empowers students to actively control their growth and align it with their future development orientation.

STEM Education

STEM education has become increasingly popular in Vietnam as it prepares students for a rapidly changing job market (MOET, 2018). By integrating science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, students are taught to think critically, collaborate, and problem-solve in real-world contexts. This approach to education also helps students develop a passion for these subjects and a desire to pursue careers in STEM fields. Through STEM education, students can gain a better understanding of the practical applications of these subjects and how they can be used to address societal issues. It is hoped that this will ultimately lead to a more skilled workforce and a stronger economy (Hoang, 2022; Tiep, 2017).

Vietnam is undergoing a period of educational innovation, strongly shifting the educational process, mainly from equipping knowledge to comprehensively developing students’ competencies and qualities (Tri, 2021). Initially, educators deploy STEM education to support the implementation of new educational programs. STEM education gives students in diverse situations and circumstances that require critical thinking the opportunity to develop and apply various knowledge, skills, and creative thinking and problem-solving skills to come up with solutions in various ways to achieve better results and promote self-confidence and creativity (Chen et al., 2021). However, Vietnam lacks a formal STEM curriculum. STEM education currently encourages the integration of STEM elements into lessons to develop competency. Each assessment type necessitates specific tools. The rubric will support students in monitoring and self-assessing their abilities. To gauge the effectiveness of STEM learning, teachers primarily use traditional paper-based tests from subjects like science, technology, and mathematics (Chen et al., 2021; Le et al., 2021).

STEM Career Interest

Interest is a cognitive state that motivates individuals to pay attention to a particular issue or activity (Cheng et al., 2021; Silvia, 2006). In education, students’ interests are divided into two types:

-

Personal interest and

-

Situational interest.

Personal interest, which reflects the individual’s inclination and intrinsic motivation towards certain activities, topics, or fields, is considered a sustainable emotion (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Besides, situational interest refers to the impact of contextual factors that arouse curiosity and emotions in individuals within a particular situation (Krapp & Prenzel, 2011). Although situational interest is considered a temporary emotion, the association of the specific content or field situation makes the emotion last longer to form and reinforce personal interest in that topic or field (Oh et al., 2013). According to Luo and colleagues (2021), STEM career interest (CI) is the personal interest in choosing a career related to the STEM field. Therefore, within the scope of research, students’ STEM career interest is a cognitive state that motivates them to pay attention to careers related to the specific STEM field.

Self-efficacy and outcome expectations are the motivational factors that most influence the development of students’ interest in STEM careers (Jiang et al., 2024; Sahin & Waxman, 2021). In the STEM field, self-efficacy is a psychological attribute that represents one’s belief in their ability to perform specific behaviors or actions. Outcome expectations refer to students’ anticipation of the results of performing a behavior. When students choose STEM careers, they are concerned with the pathways that will lead them to success. Students with higher outcome expectations and self-efficacy are more likely to major in STEM disciplines and succeed in STEM fields (Luo et al., 2021). Through STEM career interest, expectations about outcomes and self-efficacy influence the goal of choosing a STEM career, thereby motivating students to take specific actions to pursue their career goals (Blotnicky et al., 2018).

For example, students considering a career in engineering may participate in a robotics competition. However, if they find it difficult to complete the required tasks, they may reconsider their initial career choice. Based on their perceived abilities and expectations of outcomes, their interests and career goals may shift, leading them to choose an alternative career path (Roller et al., 2020).

The expectations of others (e.g., parents, teachers, and peers) play an important role in shaping students’ interest in STEM careers (Sahin & Waxman, 2021). Depending on the situation, these expectations can serve as either motivators or barriers for high school students when making STEM career decisions. Students’ academic success and career choices are strongly influenced by the expectations of their parents and teachers. Parents who aspire for their children to work in scientific fields play a significant role by encouraging their participation in scientific activities. This hypothesis suggests that parental expectations can foster an interest in science. In particular, parental expectations have a greater influence on students choosing to study STEM majors at the university level (Hui & Lent, 2018).

STEM experiences are contextual factors that promote STEM career interest. These experiences include in-school and out-of-school STEM programs, STEM clubs, STEM summer camps, and STEM courses. Students who participate in formal STEM courses are more likely to develop an interest in STEM careers. A study by Rozek et al. (2017) revealed that students who engage in numerous STEM courses and score higher on the ACT (American College Testing) are more likely to pursue a STEM major.

Interest in STEM careers also exhibits gender disparities (Turner et al., 2019). Males tend to be more interested in analytical STEM careers such as engineering, physics, chemistry, mathematics, economics, and computer science. Meanwhile, females, despite having strong computational aptitude and good academic performance, show less interest in these STEM fields (Roller et al., 2020).

Measuring STEM career interest requires relying on the subject’s visual attention to an object manifested through behaviors. The behavioral expression of students’ STEM career interest is demonstrated through their interest in STEM professions characterized by activities such as conducting research in laboratories or factories; studying scholarly resources to explore new knowledge in various fields; using computers for programming, software design, data analysis, and information processing; creating new products or improvements to enhance life; and managing and coordinating teamwork and activities in solving scientific and technical problems.

STEM education plays a crucial role in addressing the shortage of high-quality human resources in STEM occupations. This scarcity is evident not only in the United States (Varas, 2016) and Germany (Schönfeld et al., 2020) but also in countries like Vietnam (Hung, 2016, 2017). To bridge this gap, educational experts emphasize the need for innovative educational approaches that focus on students’ abilities and future career choices (Lucas, 2021). However, students often face challenges when deciding on a career path, leading to negative emotions. Career interest is a significant factor influencing students’ career choices and subsequently impacting their goals and commitment to future career activities (Blotnicky et al., 2018). Therefore, researchers and educators are increasingly exploring the importance of generating interest in STEM careers to meet the demands of the evolving job market.

In the context of Vietnam’s reform of the general education program, the STEM education model is considered an important solution to achieve career-oriented goals for students (Prime Minister, 2017; MOET, 2018). However, currently, there are no specific instructions on organizing and evaluating teaching activities according to career-oriented STEM education by focusing on arousing students’ interest in STEM careers. Meanwhile, the percentage of high school students choosing to study subjects in the fields of science, technology, and engineering (STEM subjects) tends to decrease, partly reflecting their interest in science, technology, and engineering (STEM subjects). STEM careers among students are on the decline (Tiep, 2017).

For that reason, this study was conducted with the following main purpose: to explore the impact of teacher assessment results through scores of related subjects and self-assessment results on learning ability. STEM education-oriented training for STEM career interests of high school students.

Because of how important self-evaluation is in shaping students’ interests in STEM careers and the fact that there isn’t a strong link between how well students do in STEM classes and how well they think they do in STEM subjects, this study aims to find out what really makes students interested in STEM careers. Specifically, this research aims to address the following key questions:

RQ1 How does self-assessment of STEM competencies influence students’ interest in STEM careers?

RQ2 To what extent do test scores in STEM subjects impact students’ STEM career interests?

RQ3 What role does the integration of STEM experiential activities and subject content play in shaping students’ perceptions of STEM careers?

RQ4 How does academic performance in STEM subjects correlate with students’ self-perception of their STEM abilities?

By addressing these research questions, the study provides insights into the relationship between students’ self-assessment, academic achievement, and career aspirations in STEM fields. The findings contribute to the ongoing discourse on improving STEM education by highlighting the importance of fostering self-awareness and aligning educational practices with career development strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Theoretical Model of the Impact of STEM Achievement and STEM Self-Efficacy on Students’ STEM Career Interest

In general, making a decision about a particular occupational pathway is a behavior influenced by both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. According to Eccles et al.’s (1983) Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation, one of its key assumptions highlights how interest value affects children’s and teenagers’ career decisions, along with other factors. Within the scope of occupational choices, it is understandable that interest in a specific career field reflects a willingness to engage persistently in deeper levels of academic cognition to succeed in that occupation, thereby promoting decision-making (Wang & Degol, 2013). This suggests that the pivotal determinant in students’ career orientation is the enhancement of their career interest.

The Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) was developed based on Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1977), which examines individuals’ confidence in their abilities and their perceived suitability for a particular profession (Kier et al., 2014). SCCT posits that career interest is primarily influenced by self-efficacy and outcome expectations (Kier et al., 2014; Lent et al., 1994, 2018). In the context of STEM education, students’ scores in STEM subjects reflect their outcome expectations, as these scores measure their knowledge relative to career requirements. This implies that students tend to pursue careers that align with the knowledge they possess (Blotnicky et al., 2018). In the Vietnamese context, teachers rather than students themselves assess this knowledge, and such assessments are considered an indicator of STEM achievement (AC). Therefore, this study adopts the SCCT framework to analyze how STEM self-efficacy (SE) and STEM achievement influence STEM career interest, thereby shaping students’ career choices.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to achieve job-related outcomes (“I know I can do it”) (Bandura, 1977; In’am & Sutrisno, 2021), while outcome expectations refer to one’s belief in the benefits that a given behavior will bring (“What will this behavior do for me?”). In STEM education, students’ STEM self-efficacy is demonstrated through their confidence in applying integrated knowledge and skills from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to solve real-world problems and create value for themselves and their communities (Nga et al., 2022). It also encompasses their self-belief in their ability to perform STEM-related learning tasks (Luo et al., 2021). However, individuals’ self-beliefs are shaped by psychological factors and are nurtured through social relationships and collaborative activities rather than in isolation (Flanagan & Gallay, 2014). Thus, it is crucial to provide students with STEM experiences during their learning process.

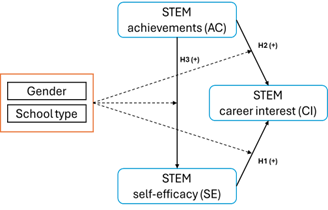

This study’s theoretical model considers three key factors: STEM career interest, STEM self-efficacy, and STEM achievement in STEM subjects. Specifically, this article focuses on the direct impact of STEM achievement on STEM career interest and the indirect impact of STEM achievement on STEM career interest through STEM self-efficacy. Based on the relationships among these three factors, this study proposes three hypotheses, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Furthermore, according to expectancy-value theory, gender influences students’ interests due to biological and psychological factors, including behavioral tendencies and hormonal effects on competence development. Meanwhile, school type serves as a contextual factor that shapes students’ interests (Wang & Degol, 2013). To explore whether gender and school type contribute to differences in students’ career interests, this study will incorporate multi-group analyses during the research process.

Hypothesis H1: Students’ Self-Efficacy of STEM Competency Positively Affects Their STEM Career Interest

Higher self-efficacy leads to students’ greater interest, which gives information about their likelihood of positive actions in the future (Schunk & Pajares, 2002; Turner et al., 2019). Based on STEM competence framework of Nga et al. (2022) and Trung et al. (2022), students can assess their competencies based on aspects of information collecting and processing (SE-IN), solution implementation and community sharing (SE-PS) and using technical equipment and tools to solve problems in STEM fields (SE-TE). Through that, students determine suitability with STEM careers and activate students’ interests in STEM careers (Jiang et al., 2024; Maiorca et al., 2021; Mau et al., 2020).

Hypothesis H2: Students’ STEM Achievement Positively Affects Their STEM Career Interests

In Vietnam’s educational context, students’ achievements are still used mainly in schools to assess learning effectiveness. Within the scope of research on STEM education, the academic achievement scale (STEM achievement - AC) is built by students’ grades in STEM-related subjects such as mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, technology, and informatics. Some preliminary research depicts a connection between students’ grades and career interests. For example, junior high school students with high math grades are more likely to show interest in STEM careers than high school students (Blotnicky et al., 2018; Sadler et al., 2012) grades in STEM subjects also have an impact on students’ interests in science careers (Šimunović & Babarović, 2021). Thus, grades of STEM subjects are used to reflect teachers’ assessment of students’ suitability for STEM careers.

Hypothesis H3: Students’ STEM Achievement Positively Affects Their STEM Self-Efficacy

Grades in STEM subjects are related to students’ STEM self-efficacy. Grades in STEM subjects serve as a basis for students to assess their STEM competency. STEM grades reflect information about the level of knowledge related to STEM subjects and students’ competency to apply that knowledge to solve problems. Based on the reflection of STEM grades, students compare and self-assess their own STEM competency, forming accurate perceptions of their STEM competency (Blotnicky et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2021). Therefore, a theoretical model explains the indirect impact of achievements on STEM career interest through STEM self-efficacy.

To guarantee reliability, the study examined the internal consistency of the results across different gender groups and school types. Combining the hypotheses above, Figure 1 describes the research model on the impact of assessment activities on students’ interests in STEM careers.

Methodology

Guided by the principles of mixed-method research design, as outlined in previous studies (Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Johnson & Christensen, 2019), the study was structured into two distinct phases.

Phase 1

Phase 1 commenced with an extensive review of international literature to identify factors influencing students’ interest in STEM careers. This process enabled us to adapt and select preliminary scales and constructs relevant to the Vietnamese educational context. Following this, a structured interview questionnaire was administered to a voluntary sample of 10 students and 5 teachers, all of whom have substantial experience with STEM education in various high schools across Vietnam. The data obtained from these interviews are considered reliable due to the consistency in curriculum and adherence to educational policies set forth by the Vietnamese Ministry of Education and Training, despite regional differences. The insights gained were crucial in refining the questionnaire and in identifying factors that influence the evaluation and self-assessment of students’ competencies in STEM education within Vietnamese schools.

Phase 2

Phase 2 involved conducting a quantitative survey with a sufficiently large sample to evaluate the reliability and validity of the scales. The results of this survey, detailed in the subsequent section, confirm the suitability of these scales for the formal survey. The official survey was then conducted using the snowball sampling technique (Chiriacescu et al., 2023), resulting in the collection of 597 student responses from Ho Chi Minh City, where the authors are based. This technique was selected due to specific contextual and logistical considerations in the Vietnamese educational system. Firstly, access to student populations in public high schools requires formal administrative approval at multiple levels, making random sampling difficult to implement practically. Snowball sampling allowed the researchers to reach target respondents—students who had direct exposure to STEM activities—through initial contacts with cooperating teachers and educational partners. Secondly, this method enabled us to identify and recruit participants from diverse types of schools and districts, which contributed to the heterogeneity of the dataset. While this approach does not allow for full statistical generalizability, it was appropriate for the exploratory objectives of this study and the need to reach a specialized student population with relevant STEM experience. These responses provided a robust dataset for statistical analysis. The data were analysed using SmartPLS version 4.0.9.2, in accordance with the established hypotheses. Several steps were taken in the analysis to make sure the results were accurate and reliable. Multivariate statistical analysis using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was used (Table 1). PLS-SEM is particularly useful in exploratory research for theory building, as it estimates path coefficients to maximise the R² coefficient of determination of latent variables. This study used the strategy of repeated observed variables to look at the variable STEM self-efficacy, which is a quadratic variable in the form of a result-outcome figure.

Table 1. Criteria for evaluating measurement models and structural models when using the PLS-SEM method

|

The analysis was conducted in three key stages:

Stage 1: Evaluation of measurement models

Measurement models were examined for convergent validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency reliability. These models show how observed indicators relate to latent variables.

Stage 2: Evaluation of structural models

Structural models, representing relationships between latent variables, were assessed through a series of steps, including checks for multicollinearity, model fit, path coefficient analysis, determination of the R² coefficient, evaluation of f² effect size, and assessment of Q² predictive relevance.

Stage 3: Multi-group analysis

After testing the hypotheses, the study looked at the path coefficients for different groups of students based on their gender and school type using multi-group analysis. Partial Least Squares multi-group analysis (PLS-MGA), as recommended by Sarstedt et al. (2011), was employed to examine potential differences in group-specific parameter estimates (e.g., path coefficients). Differences were considered statistically significant at the 5% level when the p-value for a path coefficient difference was less than 0.05.

These findings, alongside previous research on factors affecting STEM career interest through assessment activities, provide a solid foundation for further discussions within this study.

In light of the aforementioned considerations, it is clear that the mixed-method research design, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative approaches as advocated by Creswell and Creswell (2017), is well-suited to achieving our research objectives.

Participants

According to Official Dispatch No. 3089, which outlines national objectives for STEM education in high schools, 50% of schools are expected to implement STEM activities by 2025 and 80% by 2030. Most participating schools had initiated STEM education at varying levels, including integrated lessons within the formal curriculum, extracurricular clubs, and student participation in STEM-related competitions. However, the implementation remains inconsistent, primarily due to disparities in teachers’ capacity to design and deliver STEM lessons. Additional barriers to integrated instruction include limited classroom time, subject specialization, and students’ elective subject choices.

To ensure meaningful participation, only students with at least one verifiable STEM learning experience were retained in the final dataset. Moreover, researchers collected detailed information about each participating school—such as the types of STEM programs offered, the professional qualifications of STEM instructors, and the availability of educational infrastructure—to support the selection of survey sites.

This research employs the cumulative random sampling method to collect data from students in nine high schools in Ho Chi Minh city. A total of 885 responses were initially collected. After removing cases with no prior exposure to STEM-related education, 597 valid responses remained (mean age = 16.4 ± 0.3 years): 402 from public schools, 118 from specialized schools, and 77 from private schools. This sample size meets the minimum recommended threshold for linear modeling techniques, as suggested by Hair et al. (2019), who advocate a minimum of 300 participants for structural equation modeling. The data collection process adhered to established ethical standards, including informed consent and strict confidentiality protocols. Additional participant characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Statistical characteristics of the participants

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RESULT

Details of the survey instruments, including students’ self-reported grades and the STEM competency questionnaire, are provided in Appendix Table 1A and Table 2A.

Measurement Model Evaluation Results

As shown in Table 3, all constructs demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and indicator reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values exceeding recommended thresholds. The composite reliability coefficient (CR: 0.898 - 0.938) is also greater than 0.7, indicating high reliability. Furthermore, the concepts in the model achieve convergent validity with an average extracted variance (AVE) greater than 0.5. The measurement model is described by the external loading factor, with concepts having external loading coefficients ranging from 0.757 to 0.904. These coefficients are greater than 0.708, indicating that the quality of the observed variables in the model is guaranteed.

Table 3. Results of the reliability and validity of the scale

|

In addition, to evaluate the discrimination of the concepts in the model, it is necessary to consider evaluating the uniqueness-difference ratio coefficient. The results extracted from the model show that the distinction between concepts is guaranteed because the HTMT coefficients are all lower than the accepted value of 0.85 (See Table 4).

Table 4. Results of evaluating discrimination using Heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio

|

Results of Structural Model Evaluation

The structural model was evaluated based on multicollinearity diagnostics, path coefficients, effect sizes, and the model’s explanatory and predictive power. As shown in Table 5, all predictor constructs exhibit Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values below the threshold of 5 (range: 1.000 to 1.082), indicating no multicollinearity concerns and ensuring the reliability of the estimated path coefficients.

Table 5. Multicollinearity assessment via VIF

|

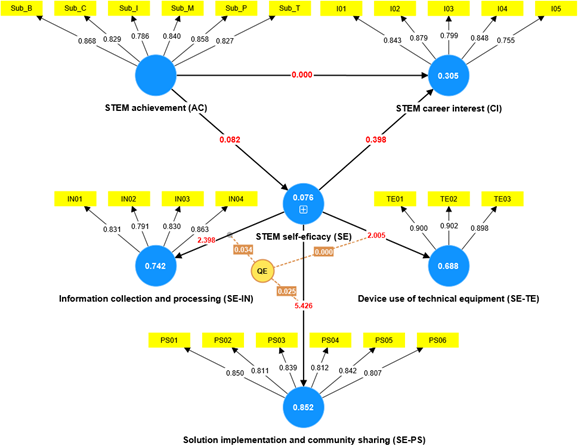

Figure 2 presents the PLS-SEM path model, including the outer loadings (black), effect sizes (f²; red), and explained variance (R²; white), processed using SmartPLS software. The R² values indicate that academic achievement (AC) accounts for 7.6% of the variance in self-efficacy (SE), while SE explains 30.5% of the variance in career interest (CI). These results support the model’s explanatory power and address Research Question 3, which explores the role of STEM-related self-efficacy in shaping career interest.

The model’s predictive relevance was further evaluated through Q² values, confirming acceptable predictive accuracy for both endogenous variables (Q²SE = 0.041; Q²CI = 0.201).

The results reveal that self-efficacy exerts a significant and strong direct effect on career interest (β = 0.547, p < 0.001,

f²= 0.398), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. A summary of the direct, indirect, and total effects among the constructs is presented in Table 6, highlighting the mediating role of STEM self-efficacy. This finding aligns with previous research (e.g., Turner et al., 2019; Mau et al., 2020), which has also emphasized the positive influence of STEM-related self-efficacy on students’ interest in STEM careers.

Table 6. Summary of results of direct and indirect impacts on the model

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In contrast, STEM achievement (AC) did not demonstrate a significant direct effect on career interest (CI) (β = 0.018, p = 0.591, f² = 0.000), offering no support for Hypothesis 2. This result diverges from prior studies (e.g., Jiang et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2021) that reported positive associations between academic performance and STEM career interest. The finding suggests that academic test scores alone may be insufficient predictors of students’ career orientations, highlighting a potential disconnect between traditional assessment practices and students’ intrinsic career motivations.

Nevertheless, AC exhibited a moderate direct effect on self-efficacy (β = 0.275, p < 0.001, f² = 0.082), confirming Hypothesis 3. This indicates that while academic success contributes to students’ confidence in their STEM abilities, it does not wholly determine their self-efficacy.

Importantly, the study identified a significant indirect effect of academic achievement on career interest through self-efficacy (β = 0.150, p < 0.001), underscoring the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between academic performance and career intentions. This finding directly addresses Research Questions 1 and 4, emphasizing the critical role of students’ self-perceived competencies in shaping their STEM career pathways.

Additionally, the absence of a direct relationship between academic achievement and career interest (AC → CI) offers insights into Research Question 2. It suggests that test-based academic outcomes may not exert a strong influence on students’ career choices. Instead, self-efficacy emerges as the more salient predictor, reinforcing calls for educational reform efforts that embed self-assessment, reflective learning, and authentic performance tasks into STEM curricula and career guidance practices.

Taken together, these findings highlight the central role of self-efficacy in students’ STEM career development. While academic performance remains relevant, it is students’ belief in their own capabilities that more directly drives their interest in pursuing STEM-related futures.

Multidimensional Structural Analysis

Table 7 shows the impact of gender factors on the research model under consideration. The results showed no difference in the path coefficients of all relationships in the model for these two groups (p: 0.500 - 0 .714).

Table 7. Results of bootstrapping the structural model with the effects of gender

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to Table 8, the impact of SE on CI in two groups of students in school type Public and Non-public are different (p = 0.036) and is stronger in the group of students studying in non-public schools than in students studying in public schools (β = 0.145 > 0). Meanwhile, the impact of the scores AC on other factors is not affected by the type of school the student is studying in (p: 0,142-0.387).

Table 8. Results bootstrapping the structural model with the effects of school type

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study highlight the critical role of students’ self-assessment of their STEM competencies in shaping their interest in STEM careers. This fits with previous studies (Kier et al., 2014; Lent et al., 1994; Luo et al., 2021; Maiorca et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2019). These studies have shown that self-perception and career interest are always linked in a good way. To support students in accurately evaluating their STEM-related abilities, educators must implement structured self-assessment practices that foster skill development and self-discipline. Effective STEM education should include specific strategies like:

-

Helping students make organised career plans that match their skills and interests with possible STEM careers,

-

Providing individualised support to improve students’ STEM-related skills, knowledge, and hands-on experience, and

-

Encouraging self-regulation so that students stay interested in self-evaluation throughout their academic journey.

These measures improve self-awareness and empower students to make informed decisions about their suitability for STEM careers, particularly when integrated with engaging, hands-on STEM learning experiences.

The powerful direct effect of STEM self-efficacy (SE) on career interest and its role as a full mediator underscores a critical leverage point for educational reform not only in Vietnam but across Southeast Asia. This finding aligns with research from Malaysia, where a study by Sagala et al. (2019) on secondary school students demonstrated that science self-efficacy was a more significant predictor of STEM career interest than even achievement in science subjects. Further strengthening this regional perspective, a comprehensive study in the Philippines by Punzalan (2022) identified self-efficacy, alongside outcome expectations and parental support, as a primary driver of career aspirations in STEM fields. The convergence of our results with these studies from key ASEAN members highlights a shared understanding emerging across the region: cultivating students’ belief in their capabilities is fundamental to reversing the decline in STEM career uptake. This research, employing a rigorous PLS-SEM methodology in the Vietnamese context, provides robust empirical validation for this shared priority. It suggests that regional collaborations focused on developing and sharing pedagogical strategies—such as project-based learning, inquiry-based science education, and authentic research experiences—that are specifically designed to boost self-efficacy could yield significant benefits for the entire ASEAN community.

A significant challenge identified in this study is the limited influence of academic test scores in STEM subjects on students’ career aspirations in STEM fields. The results indicate that test scores alone are inadequate predictors of students’ interest in pursuing STEM careers. This finding is consistent with Šimunović and Babarović’s (2021) research in Croatia, which revealed that academic achievement in STEM subjects had minimal impact on students’ interest in engineering and technology careers. One potential explanation for this disparity is the lack of a coherent connection between experiential STEM activities and formal STEM curricula. Although Vietnam’s 2018 General Education Program has attempted to integrate career orientation into STEM education, the absence of a well-structured curriculum that effectively bridges vocational education with STEM subjects remains a barrier. Without a clear integration of theoretical knowledge and practical application, students may fail to develop a comprehensive understanding of STEM fields, thereby hindering their ability to make informed career decisions.

The finding that academic test scores exert no significant direct effect on STEM career interest finds resonance in studies across diverse Asian educational contexts, suggesting a broader pattern beyond Vietnam. In Indonesia, a study by Widjaja et al. (2021) that developed a test to measure scientific reasoning skills found that while such cognitive abilities were crucial, they did not directly translate into career intentions without the mediation of affective factors like motivation. Similarly, research from Thailand by Apaivatin et al. (2021) on the “STEM Education Model” specifically noted that traditional assessment often fails to capture the creativity and problem-solving aptitudes essential for STEM careers, calling for more holistic evaluation methods. This regional consensus challenges the over-reliance on standardized test scores as a proxy for career readiness. This study from Vietnam provides robust quantitative evidence for this argument, demonstrating through a well-fitting structural model that the pathway from achievement to career interest is fully mediated by self-efficacy. This offers a clear mechanistic explanation for a phenomenon observed in neighboring countries, strengthening the case for regional policy shifts towards assessment reform that values and measures competencies beyond academic grades.

Also, this study backs up earlier research (Pratiwi et al., 2021; Soland, 2019) that found a weak link between how well students did in STEM classes and how well they thought they were doing in STEM. High test scores do not necessarily equate to greater confidence in pursuing STEM careers. In Vietnam, where academic performance heavily influences students’ self-concept in STEM, it is imperative for educators to evaluate students’ competencies beyond traditional test scores. By adopting a more holistic approach to assessment, teachers can help students gain a clearer understanding of their strengths and capabilities. This approach enhances students’ self-awareness and encourages a more informed and proactive approach to STEM career planning. Ultimately, such measures ensure that students are better prepared to make meaningful educational and professional choices in STEM fields, fostering a more robust pipeline of future STEM professionals.

This study offers valuable insights into the current state of assessment practices in STEM education for Vietnamese secondary school students. However, we should acknowledge several limitations. First, focussing only on English and Vietnamese literature might have left out important studies written in other languages, limiting the cultural and contextual scope of the analysis (British Educational Research Association, 2018). Secondly, the dataset’s limited scope within a single educational and cultural setting limits the generalisability of the findings. This highlights the necessity for future comparative studies that examine assessment practices across diverse educational systems and regional contexts. Also, because Vietnam is still in the early stages of reforming its general education program, there is still some variation between schools in how STEM-focused lessons are taught and how they are graded (Duong et al., 2024; Trung et al., 2024). This lack of synchronisation presents challenges in obtaining a representative sample, thereby limiting the robustness of the study’s findings. Furthermore, the study’s reliance on self-reported data raises the possibility of response bias, which may affect the accuracy of the results. To get around this problem, researchers in the future could use mixed-methods designs or longitudinal studies with bigger and more varied samples (Andrade, 2020). Taking these limitations into account would make the results more reliable and useful in a wider range of educational settings, giving us a better picture of how assessments are used in STEM subjects. This study aims to explore two moderating variables, consisting of gender and type of schools. Other moderating variables that have not been considered which is the limitation in this study. It is an opportunity to conduct the next study.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the article presents the findings of a survey conducted to examine the impact of assessment activities on the STEM career interest of high school students in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The quantitative analysis revealed that two out of three hypotheses put forth by the authors were supported. These findings shed light on the current state of assessment activities in schools in Ho Chi Minh City and Vietnam as a whole. To enhance students’ interest in STEM careers and improve the quality of assessment activities, the authors recommend improving the assessment tools in STEM education and employing diverse methods of testing and evaluation. Additionally, they suggest guiding students in developing monitoring plans and fostering self-discipline in their STEM education. The study also indicates that assessment activities account for only 30.5% of the variation in students’ STEM career interests, leaving 69.5% unexplained. Thus, future research should expand the structural model by including factors that influence students’ STEM career interests and explore the effects of STEM career interests on students’ career choices and behaviors.

On the other hand, according to current data, the number of students who choose to pursue STEM occupations decreases, showing the decline of STEM career interest of Vietnamese students. Based on these findings, educators can adjust the teaching activities on their lesson plans to concentrate on the enhancement of student’s STEM career interest. Simultaneously, teachers can consider self-assessment a way of reflecting a student’s STEM competency, besides traditional assessment methods, such as score-based evaluation from teachers. As a result, students’ cognition and belief of their own STEM competency meet the requirements of the labor market, which motivate them to pursue STEM occupations in the future.

Based on these findings, educators can adjust the teaching activities to their lesson plans to concentrate on the enhancement of students’ STEM career interest. Simultaneously, teachers can consider self-assessment a way of reflecting a student’s STEM competency, besides traditional assessment methods, such as score-based evaluation from teachers. At the same time, by a thorough understanding about STEM career interest, teachers can evaluate whether the assessment results and developing suggestions are meaningful and appropriate. Simultaneously, while Vietnam education curriculum has been improving through changing educational goals which focus on the development of students’ interest, these findings reflect effectively the efficiency of these changes. Not only to be a compass of students’ development, but this research also proves that the updated educational policies have successfully targeted the development of students’ interest, through periodically organizing STEM lessons or STEM experience activities at most education institutions. As a result, students’ cognition and belief of their own STEM competency meet the requirements of the labor market, which motivates them to pursue STEM occupations in the future.

Author contributions: TTT: Research idea provided, data collection, paper writing; XQTT: Provide new ideas in paper review, results and discussion, paper writing; PUN: Provide new ideas in paper review, provide new ideas in results and discussion; NHT: Research idea provided, paper organization, paper review. All authors agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Ho Chi Minh City University of Education for institutional support and facilitation throughout the research process.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that ethical principles for educational research were strictly observed. At the time of data collection, formal institutional ethical approval was not required according to the policies of the authors’ institution. Participation was voluntary, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and anonymity and confidentiality were ensured.

AI statement: The authors stated that QuillBot was used only for spelling and grammar checking. The authors are fully responsible for all aspects of the research and manuscript content.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

APPENDIX

The Survey Supplementary

Table 1A

Table 1A. Average score of some subjects in the most recent semester (rounded to an integer)

|

Table 2A

Table 2A. Survey on STEM competency of high school students

|

References

- Andrade, C. (2020). The limitations of online surveys. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(6), 575-576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620957496

- Apaivatin, R., Srikoon, S., & Mungngam, P. (2021). Research synthesis of STEM Education effected on science process skills in Thailand. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 1835(1), Article 012087. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1835/1/012087

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Blotnicky, K. A., Franz-Odendaal, T., French, F., & Joy, P. (2018). A study of the correlation between STEM career knowledge, mathematics self-efficacy, career interests, and career activities on the likelihood of pursuing a STEM career among middle school students. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), Article 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0118-3

- British Educational Research Association. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th edition). https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethicalguidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Chen, D. J., Lutomia, A. N., & Pham, V. T. (2021). STEM education and STEM-focused career development in Vietnam. Human resource development in Vietnam (pp. 173-198). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51533-1_7

- Cheng, L., Antonenko, P. P., Ritzhaupt, A. D., & MacFadden, B. (2021). Exploring the role of 3D printing and STEM integration levels in students’ STEM caree interest. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(3), 1262-1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13077

- Chiriacescu, F. S., Chiriacescu, B., Grecu, A. E., Miron, C., Panisoara, I. O., & Lazar, I. M. (2023). Secondary teachers’ competencies and attitude: A mediated multigroup model based on usefulness and enjoyment to examine the differences between key dimensions of STEM teaching practice. PLoS ONE, 18(1), Article e0279986. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279986

- Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publisher.

- Duong, N. H., Nam, N. H., & Trung, T. T. (2024). Factors affecting the implementation of STEAM education among primary school teachers in various countries and Vietnamese educators: Comparative analysis. Education 3-13, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2024.2318239

- Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives (pp. 75-146). W. H. Freeman.

- Elmore, R. F. (2019). The future of learning and the future of assessment. ECNU Review of Education, 2(3), 328-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531119878962

- Flanagan, C., & Gallay, E. (2014). Adolescents’ theories of the commons. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 46, 33-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800285-8.00002-9

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage.

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

- Hoang, L. H. (2022). STEM education in the 2018 general education program: Orientation and implementation organization. Vietnam Journal of Education, 2(516), 1-6.

- Hui, K. L., & Lent, R. W. (2018). The roles of family, culture, and social cognitive variables in the career interests and goals of Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(1), 98-109. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000235

- Hung, V. X. (2016). Theoretical and practical basis for developing professional skills contributing to improving national competitiveness in the context of integration. Institute of Vocational Education Studies, Hanoi. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13791.56482

- Hung, V. X. (2017). Vietnam vocational education report 2015. Hanoi: National Institute for Vocational Education and Training.

- In’am, A., & Sutrisno, E. S. (2021). Strengthening students’ self-efficacy and motivation in learning mathematics through the cooperative learning model. International Journal of Instruction, 14(1), 395-410. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14123a

- Jiang, H., Zhang, L., & Zhang, W. (2024). Influence of career awareness on STEM career interests: Examining the roles of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and gender. International Journal of STEM Education, 11, Article 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-024-00482-7

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. B. (2019). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (7th edition). SAGE Publications.

- Kier, M. W., Blanchard, M. R., Osborne, J. W., & Albert, J. L. (2014). The development of the STEM career interest survey (STEM-CIS). Research in Science Education, 44, 461-481. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-024-00482-7

- Krapp, A., & Prenzel, M. (2011). Research on interest in science: Theories, methods, and findings. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 27-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.518645

- Le, L. T. B., Tran, T. T., & Tran, N. H. (2021). Challenges to STEM education in Vietnamese high school contexts. Heliyon, 7(12), Article e08649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08649

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79-122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

- Lent, R. W., Sheu, H.-B., Miller, M. J., Cusick, M. E., Penn, L. T., & Truong, N. N. (2018). Predictors of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics choice options: A meta-analytic path analysis of the social-cognitive choice model by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(1), 17-35. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000243

- Looney, J. (2009). Assessment and innovation in education. OECD Education Working Papers, Article 24. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/222814543073

- Lucas, B. (2021). Rethinking assessment in education: The case for change. Victoria: Book publishing and rights Co. LLC.

- Luo, T., So, W. W. M., Wan, Z. H., & Li, W. C. (2021). STEM stereotypes predict students’ STEM career interest via self-efficacy and outcome expectations. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), Article 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-021-00295-y

- Maiorca, C., Roberts, T., Jackson, C., Bush, S., Delaney, A., Mohr-Schroeder, M. J., & Soledad, &. S. (2021). Informal learning environments and impact on interest in STEM careers. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 19, 45-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-019-10038-9

- Mau, W.-C. J., Chen, S.-J., & Lin, C.-C. (2020). Social cognitive factors of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics career interests. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 21(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-020-09427-2

- McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger student motivation and higher achievement. Educational Horizons, 87(1), 40-49.

- MOET. (2018). General education program. Hanoi.

- Nga, N. T., Quynh, T. T., Uyen, N. P., & Trung, T. T. (2022). An overview study on STEM competencies in the world and propose a STEM competency framework for high school students in Vietnam. Vietnam Journal of Education, 22(10), 48-53. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34725.99043

- Oh, Y. J., Jia, Y., Lorentson, M., & LaBanca, F. (2013). Development of the educational and career interest scale in science, technology, and mathematics for high school students. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 22, 780-790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-012-9430-8

- Pratiwi, L. E., Laily, N., & Sholichah, I. F. (2021). The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement. Journal Universitas Muhammadiyah Gresik Engineering, Social Science, and Health International Conference, 1(2), 851-855. https://doi.org/10.30587/umgeshic.v1i2.3462

- Prime Minister. (2017). Directive on strengthening access to industrial revolution 4.0 (Vols. 16/CT-TTg). Hanoi.

- Punzalan, C. H. (2022). STEM interests and future career perspectives of junior high school students: A gender study. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 8(1), 93-102. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijres.2537

- Roller, S. A., Lampley, S. A., Dillihunt, M. L., Benfield, M. P., Gholston, D. E., Turner, M. W., & Davis, A. M. (2020). Development and initial validation of the student interest and choice in STEM (SIC-STEM) survey 2.0 instrument for assessment of the social cognitive career theory constructs. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 29(5), 646-657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-020-09843-7

- Rozek, C. S., Svoboda, R. C., Harackiewicz, J. M., Hulleman, C. S., & Hyde, J. S. (2017). Utility-value intervention with parents increases students’ STEM preparation and career pursuit. PNAS, 114(5), 909-914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607386114

- Sadler, P., Sonnert, G., Hazari, Z., & Tai, R. (2012). Stability and volatility of STEM career interest in high school: A gender study. Science Education, 96(3), 411-427. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21007

- Sagala, R., Umam, R., Thahir, A., Saregar, A., & Wardani, I. (2019). The effectiveness of STEM-based on gender differences: The impact of physics concept understanding. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 753-761. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.8.3.753

- Sahin, A., & Waxman, H. C. (2021). Factors affecting high school students’ STEM career interest: Findings from a 4-year study. Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, 22(3), 279-304. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1342524

- Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J., & Ringle, C. M. (2011). Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. In M. Sarstedt, M. Schwaiger, & C. R. Taylor (Eds.), Measurement and Research Methods in International Marketing (pp. 195-218). https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2011)0000022012

- Schönfeld, G., Wenzelmann, F., Pfeifer, H., Risius, P., & Wehner, C. (2020). Training in Germany – an investment to counter the skilled worker shortage. Results of the 2017/18 BIBB Cost-Benefit Survey. BIBB-Report, 3, 2020.

- Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. W. Eccles (Ed.), Development of achievement motivation: A volume in the educational psychology series (pp. 15-31). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012750053-9/50003-6

- Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. Oxford university. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195158557.001.0001

- Šimunović, T., & Babarović, M. (2021). The role of parental socializing behaviors in two domains of student STEM career interest. Research in Science Education, 51, 1055-1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-020-09938-6

- Soland, J. (2019). Modeling academic achievement and self-efficacy as joint developmental processes: Evidence for education, counseling, and policy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 65, Article 101076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101076

- Spiller, D. (2012). Assessment matters: Self-assessment and peer assessment. The University of Waikato.

- Tiep, P. Q. (2017). Nature and characteristics STEM education model. Vietnam Journal of Educational Sciences, 61-64. http://vjes.vnies.edu.vn/en/nature-and-characteristics-stem-education-model

- Tri, N. M. (2021). Developing education in Vietnam in the context of international integration. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the Asia Association of Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 234-240. Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210226.029

- Trung, T. T., Ngan, D. H., Nam, N. H., & Thuy, l. T. (2024). Framework for measuring high school students’ design thinking competency in STE(A)M education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 35, 557-583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-024-09922-5

- Trung, T. T., Quynh, T. X., Uyen, N. P., & Nga, N. T. (2022). Developing and standardizing a STEM competency assessment tool for high school students in Ho Chi Minh City. Ho Chi Minh City University of Education Journal of Science, 19(8), 1255-1270. https://doi.org/10.54607/hcmue.js.19.8.3408(2022)

- Turner, S. L., Joeng, J. R., Sims, M. D., Dade, S. N., & Reid, &. M. (2019). SES, gender, and STEM career interests, goals, and actions: A test of SCCT. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(1), 134-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717748665

- Varas, J. (2016, April). The native-born STEM shortage. American Action Forum. https://www.americanactionforum.org/

- Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. (2013). Motivational pathways to STEM career choices: Using expectancy–value perspective to understand individual and gender differences in STEM fields. Developmental Review, 33(4), 304-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.001

- Widjaja, W., Astra, I. M., & Wibowo, F. C. (2021). Flipped learning models and students’ scientific literacy on physics achievement test. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 2019(1), Article 012033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2019/1/012033

- Zulkosky, K. (2009). Self-efficacy: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 44(2), 93-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00132.x

How to cite this article

APA

Ta, T.-T., Tran-Thi, X.-Q., Nguyen, P.-U., & Tran, N.-H. (2026). Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

Vancouver

Ta TT, Tran-Thi XQ, Nguyen PU, Tran NH. Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1):e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

AMA

Ta TT, Tran-Thi XQ, Nguyen PU, Tran NH. Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1), e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

Chicago

Ta, Thanh-Trung, Xuan-Quynh Tran-Thi, Phuong-Uyen Nguyen, and Ngoc-Huy Tran. "Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 1 (2026): e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

Harvard

Ta, T.-T., Tran-Thi, X.-Q., Nguyen, P.-U., and Tran, N.-H. (2026). Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

MLA

Ta, Thanh-Trung et al. "Impacts of assessments on students’ STEM career interest: A Vietnam quantitative study". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2026, e2605. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17762

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)