Abstract

This literature review explores the role of intergenerational learning as a pedagogical strategy within Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development. A systematic analysis of 34 empirical studies published between 2016 and 2025 examines the interactions between children and parents regarding the transmission of environmental knowledge and the development of attitudes and behaviours. Findings indicate that intergenerational learning is not a unidirectional flow of knowledge from adults to children but a reciprocal process, where children can significantly influence their parents (reverse socialization), especially when emotionally engaged or actively involved in educational initiatives. Key moderating factors identified include the quality of the parent-child relationship, intra-family communication, the structure of interventions, and the broader sociocultural context. The review enhances understanding of intergenerational learning as a mechanism for strengthening family bonds and promoting sustainable values. It also highlights challenges related to reverse socialization, as children’s influence on adults does not always lead to long-term behavioral change. These findings underscore the need for multi-level, participatory interventions that engage both children and parents within and beyond the school environment to foster sustainable transformation.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Review Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2602

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

Publication date: 01 Jan 2026

Online publication date: 03 Dec 2025

Article Views: 1926

Article Downloads: 910

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

Given the increasingly severe environmental challenges facing the planet — such as rapid environmental degradation and the escalating threats of the climate crisis — a holistic, cross-sectoral, and long-term approach is now deemed essential (Brown, 2018). Within these efforts, children and young people are recognized as key stakeholders (Liu & Kaida, 2024), as they are the ones who will face the consequences of emerging environmental problems in the future. In order to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations, global participatory action, policy development, and the implementation of targeted measures are recommended to protect the environment and ensure the well-being of all people by 2030 (Fang et al., 2023). Despite ongoing criticism regarding the feasibility of these goals and whether they truly meet the criteria of environmental sustainability (Eisenmenger et al., 2020; Gupta & Vegelin, 2016; Luetz & Walid, 2019), renewed emphasis is placed on the role of Environmental Education (EE) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Educational interventions can lead to transformative changes toward sustainability, aiming to ensure a balance between economic growth and sustainable development, to enhance participation in sustainability-oriented actions, and to utilize technology, where appropriate, to address environmental challenges (UNESCO, 2020).

Education is considered an effective means of promoting changes in children’s attitudes and behaviours. Through the implementation of innovative EE/ESD programmes, students who actively participate acquire new knowledge, develop an experiential understanding of the impact of human activities on the natural environment, and cultivate environmental literacy skills. Moreover, through communication and interaction with their parents, they may contribute to fostering pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) within their family context as well (Ardoin & Bowers, 2020; Hartley et al., 2021; Lawson et al., 2018; Saltan & Divarci, 2017; Sihvonen et al., 2024; Vassiloudis, 2024).

Environmental literacy constitutes a critical domain, through which the development of global active citizenship can be gradually fostered (Granados-Sánchez, 2023; Hill, 2012). The concept of environmental literacy encompasses an individual’s ability to interact with the natural environment, to perceive, understand, and interpret environmental issues, and to take action to protect or restore the natural environment (Hungerford & Peyton, 1977; Roth, 1992). It is regarded as a dynamic and continuously evolving process (Roth, 1992), as personal beliefs, experiences, skills, social influences, and environmental challenges are constantly developing and changing. Family, school and peers as agents of socialization are the significant others who are major predictors of the development of personal attitudes and the occurrence of PEBs in children and adolescents (Abeliotis et al., 2010; Denault et al., 2024; Woelfel, 1972). At this point, it should be noted that although the school plays a significant role in the development and cultivation of environmental literacy, the family environment also holds a decisive role: parental support and the undertaking of initiatives complement educational efforts (Abeliotis et al., 2010; Amin et al., 2019; Jia & Yu, 2021; Suryatna, 2023). Despite the different learning theories that have been pro-posed — such as behaviorist, cognitive, and sociocognitive approaches — there is broad consensus on the decisive influence of a child’s immediate environment on the learning process (Firmansyah & Saepuloh, 2022; Zhou & Brown, 2017).

Within the framework of environmental literacy, particular emphasis is placed on intergenerational learning (IGL). It is a process through which knowledge is not the exclusive privilege of a specific age group, but is dynamically constructed through intergenerational interaction, where knowledge, attitudes, values, and behaviours are transferred not only from adults to children, but also vice versa—from children and adolescents to adults—a process known as environmental reverse socialization (Gentina & Singh, 2015; Trujillo-Torres et al., 2023). Within the family context, IGL, as an informal form of education, emerges effortlessly and unsystematically through daily experience, communication, and interaction (Zimmerman & McClain, 2015). Among the many potential benefits of IGL are not only the enhancement of knowledge transfer but also the construction of new ways of learning between generations, the strengthening of family relationships, and the promotion of social cohesion (Istead & Shapiro, 2014). Through daily interactions, and the example they set, parents contribute significantly to the cognitive, social, and emotional development of the child, as well as to the shaping of pro-environmental attitudes (PEAs), pro-environmental values (PEVs) and PEBs, transforming the environmental knowledge (EK) children acquire at school into action (Abeliotis et al., 2010; Jia & Yu, 2021). Whether as behavioral role models in everyday practice or through intentional and systematic pedagogical interventions driven by pro-environmental concern (PEC) and awareness, parents can either encourage the development of their children’s pro-environmental attitudes or, conversely, undermine the educational role of the school in fostering aspects of environmental literacy (Abeliotis et al., 2010; Eberbach & Crowley, 2017). Moreover, children and adolescents who participate in EE/ESD programmes at school can transfer the knowledge, values, and concern they have developed to their family environment, becoming agents of change within the household and motivating their parents to-ward environmentally responsible behaviours (Fitzpatrick & Halpenny, 2023; Flurry & Burns, 2005; Istead & Shapiro, 2014; Lawson et al., 2018; Spiteri, 2023).

It should be noted that the majority of research on IGL has traditionally focused on how older generations influence the EK, PEAs, PEVs, and PEBs of younger ones (Istead & Shapiro, 2014; Lawson et al., 2018), while giving limited attention to how children can, in turn, influence their parents (Spiteri, 2020). In recent years, research has increasingly highlighted these reverse influences, showing that younger generations can indeed shape the attitudes and behaviours of their parents in various areas related to sustainability and environmental protection (Brakovska & Blumberga, 2024; Lawson et al., 2018; Spiteri, 2020). It is within this framework that the present literature review is situated. It aims to systematically pre-sent the most recent empirical findings on the topic and explore the role and significance of environmental IGL within the family context, both through formal (school-based) and non-formal (non-school-based or home-based) education. Drawing on empirical data from 2016 to 2025, the review investigates how interactions between children, adolescents, and their families can foster EK, PEAs, PEVs, and PEBs, ultimately shaping sustainable practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In order to investigate the most recent developments regarding IGL in the field of EE/ESD, a systematic literature review was conducted following the principles of the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2015). Systematic reviews are commonly used across various scientific disciplines and are becoming increasingly widespread in the field of education (Alexander, 2020), as the clear and rigorous approach they provide is considered a robust method for identifying research gaps and informing future research directions (Moher et al., 2015; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). Articles were retrieved from the scientific databases ScienceDirect, Scopus, and ERIC during the first quarter of 2025 (January–April). In the identification of the sample of articles, the following keywords were used: Intergenerational learning, intergenerational transmission, parents OR family, school OR education, environment OR sustainability OR sustainable. Table 1 outlines the full criteria used in the study.

Table 1. Documents selection criteria

|

The inclusion criteria for the studies comprised peer-reviewed scientific articles written in English, published between 2016 and 2025. Empirical studies, either qualitative or quantitative, employing cross-sectional or longitudinal approaches and focusing specifically on the topic under investigation were included. Studies of educational interventions within the context of formal or non-formal education were also included, with clearly de-fined learning objectives and procedures that enabled the study, documentation, and comparative evaluation of the interventions (Ríos-Ramírez, 2023). Moreover, eligible studies were required to include children and adolescents of school age as the research sample. The methodological approaches of the selected studies had to be designed to explore the intergenerational transfer of environmental knowledge, values, and behaviours within the family context (children and parents). Specifically, the review included studies examining:

-

Reverse environmental socialization, the influence of children on their parents’ acquisition of EK or adoption of PEBs,

-

The pedagogical role of parents in the development of EK, the formation of PEAs, PEBs, PEVs, and PEC among younger family members, and

-

The interaction between children and parents in the context of IGL.

Excluded from the review were studies in which IGL was merely mentioned as a potential finding or interpretive conclusion rather than a central research focus, studies that did not explicitly address IGL within the fields of EE/ ESD, and studies that explored IGL in a broader family or social context (e.g., involving teachers, peers, community members, or grandparents).

In this literature review, the methodological strategy of Trujillo-Torres et al. (2023) was generally used. The identification and selection of studies in this systematic review adhered to the PRISMA framework (Figure 1). An initial pool of 555 records was retrieved, and duplicate entries were removed, as well as entries marked as ineligible by automation tools. Automation tools were used to exclude documents that were not related to relevant scientific domains. Using these tools, documents were selected from the subject areas of Social Sciences, Environmental Science, Education and Psychology. The remaining 258 studies underwent preliminary screening based on abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 140 publications. Of the 118 studies sought for full-text retrieval, five could not be accessed. In the next phase, each document was analyzed in detail based on the remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, from the references to the selected articles, it was found that five additional studies met the criteria that had been set and were therefore included in the final number of studies. A total of 34 published studies were included in the review.

In the Results and Discussion sections, representative in-text citations were intentionally used, where appropriate, instead of listing all relevant references at each point. In cases where the findings are supported by numerous primary studies, unless a full list of references is required, one to three illustrative references are provided as examples introduced with the abbreviation ‘e.g.’, to indicate the existence of broader supporting evidence. This approach was adopted, based on comparable examples from published literature reviews (Bevan et al., 2023; MacGregor et al., 2021) to preserve the narrative flow and overall readability, while ensuring transparent documentation of the evidence base. Excessive in-text citation density can interrupt the argumentation and reduce clarity. In this way, both the accuracy of documentation and the clarity of the presentation of findings are maintained. The complete set of included studies and study-level details is presented in the summary table of the reviewed literature (Table 2).

Table 2. Description of included studies

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RESULTS

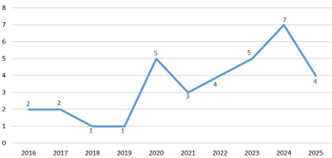

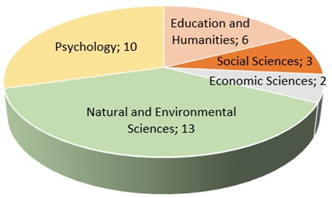

Quantitative Data

The relevant data and the main findings from each article included in the review are summarized in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the surveys have been carried out in different countries, covering a wide geographical range. The majority of studies (n = 11) have been conducted solely in China (Chen et al., 2025; Deng et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024; Jia & Yu 2021; Kong & Jia, 2023; Tian et al., 2023; Wang & Li, 2024; Wang et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025; Zhong et al., 2021), followed by United States (n = 5) (Boudet et al., 2016; Delmas et al., 2024; Gill & Lang, 2018; Lawson et al., 2019; Straub & Leahy, 2017). Two studies were conducted simultaneously in two countries (Liu et al., 2022; Liu & Kaida, 2024), while two cross-cultural studies, based on data from the PISA assessment, and included a broader range of countries (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Xia & Li, 2022). The remaining studies were carried out in a single country. Figure 2 presents the number of articles published per year. The majority of articles (n = 23) were published within the last five years (2021–2025). The articles were published in journals covering the fields of Education and Humanities, Social Sciences, Economic Sciences, Natural and Environmental Sciences and Psychology (Figure 3).

The age range of student participants in the reviewed studies spans the entire spectrum of compulsory education, from the first grade of primary school to the final year of upper secondary school (ages 6–18). Specifically, 14 studies focus exclusively on primary school students (ages 6–12) (Boudet et al., 2016; Casaló & Escario, 2016; Deng et al., 2022; Giancola et al., 2024; Gill & Lang, 2018; Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023; Harada et al., 2023; Jaime et al., 2023; Kong & Jia, 2023; Pearce et al., 2020; Pekez et al., 2025; Salazar et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2025; Zhong et al., 2021), while 11 studies pertain solely to secondary school students (ages 12–18) (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020; Delmas et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022; Parth et al., 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2023; Wang & Li, 2024; Xia & Li, 2022; Žukauskienė et al., 2021). In addition, 9 studies involve mixed-age samples of children and adolescents (Chen et al., 2025; Ding et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024; Jia & Yu, 2021; Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Lawson et al., 2019; Liu & Kaida, 2024; Straub & Leahy, 2017; Wang et al., 2025).

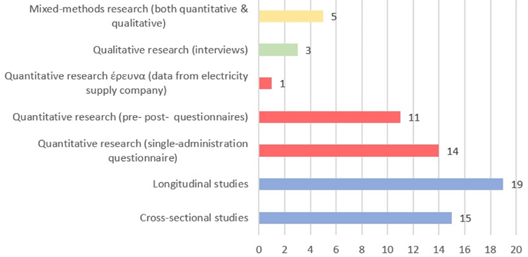

With regard to the type of research and the data collection methodology, the following information is reported and also presented in Figure 4. In terms of research design, 15 studies employed cross-sectional design, while 19 followed a longitudinal approach. Among all studies, 24 adopted a quantitative methodology. Data collection tools included both single-administration self-reported survey questionnaires (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Ding et al., 2024; Giancola et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024; Jia & Yu, 2021; Kong & Jia, 2023; Lawson et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022; Liu & Kaida, 2024; Queiroz et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020; Xia & Li, 2022; Žukauskienė et al., 2021) and pre- and post-intervention self-reported questionnaires (Boudet et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2025; Delmas et al., 2024; Harada et al., 2023; Jaime et al., 2023; Pekez et al., 2025; Straub & Leahy, 2017; Wang et al., 2025; Wang & Li, 2024; Zhang et al., 2025; Zhong et al., 2021). One additional quantitative study utilized data provided by an electricity supplier (Gill & Lang, 2018). Furthermore, three studies followed a qualitative methodology using either semi-structured (Pearce et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017) or open-ended interviews (Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020). Finally, five studies employed a mixed-methods approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative elements. In these studies, data were collected through self-reported survey questionnaires along with follow-up semi-structured interviews (Deng et al., 2022; Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023; Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Tian et al., 2023), or through an alternative qualitative approach (Delmas et al., 2024).

Cross-Sectional Studies

The vast majority of cross-sectional studies are quantitative investigations conducted with random samples of students (n = 13), except for two cases in which the sample consisted of students who had participated in school-based environmental education pro-grams (Salazar et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020). The primary data collection tool used in these studies was the single-administration survey questionnaire. In 12 studies, the questionnaire was administered to both children/adolescents and their parents (e.g., Kong & Jia, 2023; Xia & Li, 2022); in one study, it was administered to children as well as to both fathers and mothers (Giancola et al., 2024); while in another, it was administered exclusively to children (Queiroz et al., 2020). One qualitative study is also included, which employed interviews and content analysis for data collection (Pearce et al., 2020).

Among the quantitative studies, except for those relying on secondary data sources (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Liu et al., 2022; Xia & Li, 2022), all others collected primary data either through standardized questionnaires (e.g., Guan & Geng, 2024; Kong & Jia, 2023), adapted versions of standardized instruments (e.g., Jia & Yu, 2021; Lawson et al., 2019), questionnaires specifically developed for the purposes of the study (e.g., Deng et al., 2022), or through a combination of these methods (e.g., Liu & Kaida, 2024).

Most studies (n = 12) examine intergenerational effects in the formation or reinforcement of PEBs within families, as well as the mediating factors that support these behaviours (e.g., Liu et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020). Additionally, some studies focus on intergenerational influences on environmental literacy, values, or concern (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Pearce et al., 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020).

Based on the findings related to IGL, as presented in Table 2, three studies highlight IGL from children to parents (Kong & Jia, 2023; Liu et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020); five studies emphasize bidirectional intergenerational influence (Ding et al., 2024; Lawson et al., 2019; Liu & Kaida, 2024; Xia & Li, 2022; Žukauskienė et al., 2021); and seven studies identify parental influence on children (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Giancola et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024; Jia & Yu, 2021; Pearce et al., 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2022;).

Longitudinal Studies

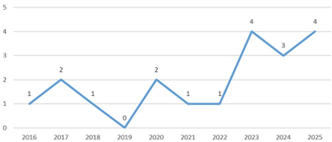

The longitudinal studies included in this review, although predominantly quantitative in nature (n = 12), exhibit considerable diversity in terms of thematic focus, intervention duration, sample characteristics, applied methodology, and data collection instruments. Specifically, the majority of these longitudinal investigations (n = 17) pertain to intervention programs conducted within both formal and non-formal educational settings (Figure 5), aiming to examine environmental reverse socialization and IGL from children to parents. Among these, 15 studies implemented school-based programmes (e.g., Jaime et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2017) combined with home-based interventions (e.g., Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023); one study employed a home-based programme (Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024), and another utilized a non-school-based programme (Boudet et al., 2016). It should also be noted that in the remaining two longitudinal studies, although no formal school-based ESD/EE programme was designed or implemented, the participating students had prior experience with similar educational initiatives (Tian et al., 2023; Wang & Li, 2024).

The primary data collection instrument employed in the quantitative studies was researcher-designed questionnaires, developed in alignment with the specific content and objectives of each study. In some cases, these instruments were adapted from or based on pre-existing questionnaires (e.g., Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2023). The topics addressed by the interventions in longitudinal studies, along with the number of studies are presented in Figure 6.

The duration of the interventions ranges from short-term activities (e.g., Chen et al., 2025) to extended implementations (e.g., Deng et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2021) that allow for the long-term observation of changes in participants’ attitudes and behaviours. The study designs primarily incorporate quantitative data collection instruments, such as pre- and post-survey questionnaires administered to both parents and children (e.g., Boudet et al., 2016; Straub & Leahy, 2017) as well as objective measurements (Deng et al., 2022; Gill & Lang, 2018). Additionally, two qualitative studies are included, both based on single-session interviews with parents and children, employing content analysis techniques (Williams et al., 2017) and qualitative ethnographic analysis (Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020), respectively. Mixed-method studies involved content analysis of follow-up interviews conducted with both children and parents (Deng et al., 2022; Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Tian et al., 2023), or solely with parents (Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023), as well as weekly check-in meetings between students and either classroom teachers or researchers (Delmas et al., 2024).

The focus on intergenerational interaction as a key variable served as a common denominator across the study designs, enabling the evaluation of the influence exerted by children on their parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and vice versa. According to the findings related to IGL, as presented in Table 2, 13 studies identified reverse socialization, from children to parents, (e.g., Pekez et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025), while 2 studies reported evidence of bidirectional intergenerational influence (Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Zhong et al., 2021). In contrast, 4 studies found no evidence that parents received IGL or were influenced by their children in ways that contributed to the development or promotion of PEAs or PEBs (Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020; Gill & Lang, 2018; Jaime et al., 2023; Straub & Leahy, 2017).

Statistical Methods in Studies and Research Limitations

The qualitative characteristics of the studies were primarily examined through in-depth content analysis (e.g., Williams et al., 2017) and analysis of pre/post differences in the variables under investigation (e.g., Delmas et al., 2024). For the analysis of quantitative data—across both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs—a wide range of statistical techniques, both parametric and non-parametric, were employed depending on the nature and availability of data. The main methods are outlined below.

To initially explore relationships among variables, descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and t-tests were applied (e.g., Giancola et al., 2024; Liu & Kaida, 2024). To estimate associations between variables and test research hypotheses, regression analyses were conducted (e.g., Ding et al., 2024; Lawson et al., 2019), along with more complex multivariate techniques such as Multivariate Facto-rial Analysis of Variance (Queiroz et al., 2020) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (Jia & Yu, 2021). Structural Equation Modeling was widely used to examine complex inter-variable relationships (Guan & Geng, 2024; Liu et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020; Žukauskienė et al., 2021). The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model was employed to explore dyadic influences between parents and children (Kong & Jia, 2023; Xia & Li, 2022), while the PROCESS macro procedure was utilized to test mediation and moderation effects among the studied variables (Giancola et al., 2024). Additionally, to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions and potential “spillover” effects on parents, the econometric Difference-in-Differences (DiD) model was applied (Jaime et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025).

While cross-sectional studies contribute to capturing trends and associations among the variables under investigation, the typical limitations of survey-based research are evident. These primarily concern the use of self-reported questionnaires (e.g., Lawson et al., 2019; Queiroz et al., 2020), which may introduce response bias. In particular, participants may provide answers that do not accurately reflect their true beliefs or behaviours but rather conform to socially desirable responses. This limitation is equally relevant in longitudinal quantitative studies that rely on similar instruments (e.g., Singh et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2021). Moreover, cross-sectional designs do not allow for the establishment of causal relationships. In studies addressing psychosocial variables without the support of qualitative inquiry (Ding et al., 2024; Giancola et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024), the subjective dimension in the assessment of constructs becomes a methodological concern. The use of secondary data derived from international datasets further limits the validity of findings. Even when country-specific analyses are conducted, the comparative presentation of results may overlook important socio-cultural contexts (Casaló & Escario, 2016; Liu et al., 2022; Xia & Li, 2022).

Longitudinal studies also exhibit methodological limitations, particularly related to sample characteristics and the statistical techniques employed. In several cases, small sample sizes were used (e.g., Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020; Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023), and analyses often relied primarily on descriptive rather than inferential statistics (Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024), thus reducing statistical power and the generalizability of results. Furthermore, many interventions were short-term (e.g., Gill & Lang, 2018; Williams et al., 2017), which negatively affects the potential for documenting sustainable changes and long-term impact on attitudes and behaviours.

DISCUSSION

Despite the aforementioned limitations, it is important to note that the diversity of statistical techniques employed in the studies included in this review, the systematic re-search design, and the variety of implemented interventions enhance the overall statistical validity of the findings and allow for meaningful estimations of relationships among study variables. Moreover, the geographical distribution of the studies indicates that, in light of increasing environmental pressures and global ecological challenges, the topic has emerged as a field of growing research interest at international level. The studies have been conducted across a range of countries, ensuring both geographical and cultural diversity and thereby strengthening the interpretive power of the findings.

An analysis of publication years and study types (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), reveals a notable in-crease in scientific interest in this area in recent years, alongside a rise in the number of articles investigating the influence of EE/ESD programmes—implemented through formal and non-formal education (non-school-based programmes, school-based programmes, or home-based activities)—on reverse socialization processes (Figure 5, Figure 6).

This literature review confirms that environmental IGL is a bidirectional process. Children and adolescents (hereinafter referred to as “children” for brevity) are not merely passive recipients of PEAs that may shape their future behaviours. Rather, they act as active transmitters of EK and as agents capable of fostering the development of PEBs within the family context. The findings highlight a range of intergenerational influence mechanisms grounded in cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal variables.

The family environment constitutes a fundamental mechanism of social learning. It is widely recognized as a critical factor in the processes of socialization and education, with intra-family relationships and interactions functioning as key channels for the transmission of EK, PEVs, PEAs, the development of PEC, and the shaping of PEBs (Denault et al., 2024; Liu & Green, 2024). Recent research included in the present scientific corpus reinforces the well-established notion that parents play a central role in shaping children’s behaviour toward the environment and sustainability. Although parents with higher levels of EK are more likely to demonstrate PEBs, knowledge alone is not a sufficient condition for fostering such behaviours in children (Kong & Jia, 2023). Rather, it is the children’s observation of their parents’ consistent PEBs, the shared participation in environmentally oriented family activities, and the quality of communication within the family that emerge as the key predictive factors for IGL from parents to children (Jia & Yu, 2021; Salazar et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2017). The importance of parental modeling and family communication — although not explicitly referenced in the theoretical frameworks commonly employed in Environmental Psychology to understand and predict PEB—can be considered fundamental. Such frameworks include the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), the Value–Belief–Norm Theory (Stern et al., 1999), the Responsible Environmental Behaviour Model (Hines et al., 1987), and the Structural Attitude–Behaviour Model (Grob, 1995). All four theories incorporate psychosocial variables such as attitudes, values, personal norms, and both cognitive and emotional factors — variables that are significantly shaped during early socialization processes and have a lasting influence on individuals’ future PEBs.

One of the most compelling findings of the present literature review is the systematic documentation of the phenomenon of reverse socialization. According to this theoretical framework, children can act as agents of environmental knowledge transfer within the family and measurably influence their parents’ PEAs and PEBs. This phenomenon is highlighted in studies that document unidirectional influence from children to parents (e.g., Casaló & Escario, 2016; Parth et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020), as well as in those identifying a bidirectional pattern of influence (e.g., Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Xia & Li, 2022; Zhong et al., 2021).

The pro-environmental knowledge conveyed by children to their parents — knowledge considered essential for transformative behavioral change (Kong & Jia, 2023) — facilitates IGL at the cognitive level (e.g., Deng et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2017). However, such knowledge is not always sufficient to induce substantive behavioral changes in parents (e.g., Parth et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). Reverse socialization in the context of IGL appears to be a multifaceted and complex phenomenon, shaped by both intra-psychological and familial or cultural factors. A critical factor is the emotional engagement and motivation of the children.

Variables such as environmental passion (Wang & Li, 2024), intrinsic motivation to act, which translates into psychological commitment on the part of the parents, and PEC (Singh et al., 2020), which often triggers emotional responses perceived by parents as signs of maturity, play a key role. Similarly, children’s moral conviction—the belief in what is “right”—when embedded in their communication of PEVs (Zhang et al., 2025), can serve as a powerful catalyst for behavioral transformation within the family. A significant moderating factor is the quality and frequency of intra-family communication (e.g., Lawson et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2023). Conscious discussions about environmental issues within the family context are strongly associated with PEBs in both parents and children (Žukauskienė et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2025). Communication, in this regard, is not merely the transmission of information; it acts as a pedagogical mechanism that fosters attitude formation and strengthens intentions through emotional involvement (Liu et al., 2022). Whether initiated by parents (e.g., Jia & Yu, 2021; Lawson et al., 2019; Straub & Leahy, 2017) or by children (e.g., Kalyanasundaram et al., 2024; Parth et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2021), intrafamilial communication functions as a critical mechanism of intergenerational transmission, serving both as a channel for knowledge dissemination and a context for mutual influence. Notably, the active role of children and their initiatives in environmental communication within the household (Tian et al., 2023) appear to significantly affect family behaviours. Children’s PEC can act as a stimulus for dialogue, heighten parental awareness, and even result in changes in pa-rental behaviours. When parents perceive that their children possess valid knowledge, express sincere environmental interest and concern, and actively attempt to communicate these values, the conditions for IGL are considerably enhanced (e.g., Singh et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2025; Žukauskienė et al., 2021).

However, for intrafamilial communication to be effective within the framework of IGL, it must be mediated by a range of family-related characteristics. Parental profiles, value systems related to the environment, the quality of the parent–child relationship (e.g., Giancola et al., 2024; Guan & Geng, 2024; Queiroz et al., 2020), parenting styles, and the nature of family communication (e.g., Guan & Geng, 2024; Wang & Li, 2024; Zhang et al., 2025) emerge as key characteristics identified in the present literature review. Children raised in family environments characterized by warm and engaged parenting styles—where parents demonstrate affection, responsiveness, and involvement—tend to develop higher levels of self-esteem, attribute greater importance to environmental protection, and are more likely to act as agents of behavioral change within the family. In contrast, authoritarian or emotionally disengaged parenting styles tend to reinforce psycho-logical barriers to change and hinder such outcomes (Queiroz et al., 2020; Xia & Li, 2022). In addition, parents’ psychological well-being, characterized by openness, rich life experiences, and emotional resilience, as well as a mindful parenting attitude (Guan & Geng, 2024), are associated with children’s ability to express themselves meaningfully and develop their own environmental discourse. Intrafamilial dialogue supports the enhancement of communication and emotional bonding and contributes to the internalization of parents’ PAVs by younger family members. Such characteristics are associated with families that follow a conversation-oriented communication style, characterized by open dialogue and frequent discussion (Wang & Li, 2024), in which parents are more receptive to information and knowledge provided by their children. Such families encourage open and free exchange of ideas, support the expression of thoughts and emotions, and allow children to participate actively in decision-making processes.

Beyond the micro-social level, which focuses on the transmission of knowledge, values, and practices within the family and immediate intergenerational interactions, this literature review highlights significant findings also at the macro-social level. The analysis is thus extended to a collective-social dimension, exploring the role of cultural differences between societies in shaping IGL. Societies characterized by high educational attainment and environmental awareness, as well as low societal power distance and high individualism — societies that reject inequalities in power and social relationships, pro-mote equality and individual autonomy — are more likely to encourage authoritative parenting strategies (Liu et al., 2022; Xia & Li, 2022). Within this context, the family views the child as an autonomous and capable individual with the right to express opinions and emotions, and encourages them to take initiative. As a result, IGL occurs from children to parents or bidirectionally, indicating a dynamic exchange of knowledge and values across generations. However, even in societies with extensive experience in environmental management and a collectively shaped pro-environmental culture — such as Japan — IGL tends to be unidirectional, with parents acting as the primary agents of guidance, due to more traditional and hierarchical family structures (Liu & Kaida, 2024). An ethnographic study conducted in Zimbabwe provides further insights (Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020): Barriers to reverse IGL include parents’ low educational attainment, which often prevents them from understanding or accepting the scientific basis of environmental issues — particularly when such concepts do not align with their lived experience. Additionally, perceptions that children lack valid or mature knowledge, economic and subsistence priorities that outweigh long-term behavioral adaptation, and the perceived threat of change as a risk to cultural continuity, all act as limiting factors to effective reverse IGL.

At this point, it is essential to highlight the significant role of EE/ESD programmes in which students participate. Both formal (e.g., Deng et al., 2022; Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023) and non-formal education initiatives (Boudet et al., 2016) play a crucial role in raising students’ environmental awareness, laying the foundation for the transmission of knowledge and the cultivation of environmental literacy skills. Particularly through school-based projects involving experiential activities, interdisciplinary approaches, and active engagement, students not only comprehend environmental challenges but are also empowered to take action and potentially become meaningful agents of change within their families via mechanisms of reverse socialization (e.g., Harada et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2023). According to Self-Determination Theory, students’ engagement in educational activities activates intrinsic motivation, encouraging them to initiate environmental discussions with their parents (Tian et al., 2023). Thus, EE/ESD programmes affect not only the students directly but also exert a less visible, yet critically important, intergenerational influence (spillover effect) by strengthening adults’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding the environment (e.g., Harada et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2023). However, participation in such programmes does not automatically lead to reverse IGL, as previously noted (Chineka & Yasukawa, 2020; Liu & Kaida, 2024), since it is also mediated by parental characteristics. The duration of school programmes, the extent of students’ active involvement, and the level of parental engagement in program-related activities are all important mediating factors in the process of IGL (Jaime et al., 2023; Straub & Leahy, 2017). The outcomes are more measurable in terms of knowledge transfer (e.g., Deng et al., 2022; Parth et al., 2020) and short-term behavioral changes within the family than in terms of long-term behaviour modification (e.g., Gill & Lang, 2018). Similarly, it is easier for families to adopt PEBs that are visible and low in functional or financial cost—such as recycling or reducing water waste — than those requiring deeper transformations in established family practices, like consumer habits or energy use (e.g., Boudet et al., 2016; Gilleran Stephens et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025).

In such cases, while students engaged in EE/ESD programmes may still act as knowledge transmitters and behavior change agents, reverse socialization alone does not lead to lasting changes in parental practices. This suggests that for meaningful and enduring IGL to occur, parallel interventions targeting adults are also necessary. Programmes that explicitly seek and facilitate parental involvement appear to yield amplified outcomes for both children and parents (e.g., Delmas et al., 2024; Harada et al., 2023). In this way, the school can emerge as a nucleus of social transition toward sustainability, empowering students to become active societal influencers and mediators of environmental education (trans-education) through reverse socialization (Zhang et al., 2025), thereby enhancing intergenerational cooperation and fostering collective environmental responsibility.

CONCLUSIONS

The present review offers a structured body of published data regarding IGL in the fields of environment and EE/ESD. However, several methodological limitations of the present review should be acknowledged. First, the inclusion criteria were restricted to English-language, peer-reviewed published articles, which led to the exclusion of studies published in other languages or included in the grey literature. Such sources may have enriched the scientific framework with alternative or culturally differentiated perspectives. Secondly, due to the large number of records initially retrieved, the early stages of the screening process relied on automation tools and on the titles and abstracts of articles, rather than full-text screening. Consequently, relevant studies may have been excluded — particularly those from less directly related scientific domains or whose relevance was not evident from their titles and abstracts. In addition, it is possible that certain keywords which could have retrieved relevant articles were omitted during the search strategy, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of the review. Finally, only a small number of comparative studies offering evidence on sociocultural differences were included. While the use of large-scale international datasets (e.g., PISA) enhances breadth, it may underestimate deeper cultural specificities that shape family perceptions, communication dynamics, and attitudes toward environmental learning. As a result, there is a risk of over-simplification in the sections of the review that attempt intercultural analysis.

In conclusion fostering environmental literacy among younger generations is a critical factor in promoting sustainable development and ensuring effective environmental protection. The development of skills, knowledge, and attitudes that enhance environmental awareness is essential for shaping citizens capable of addressing contemporary ecological challenges. This systematic literature review highlights IGL as a mutual and dynamic informal pedagogical process that takes place within the family context, playing a significant role in the transmission of EK and the cultivation of PEAs and PEBs. Re-search findings indicate that, beyond the traditional parent-to-child direction of socialization, children can also act as agents of EK, significantly influencing their parents’ perspectives and practices—a process referred to as reverse socialization. Successful environmental IGL requires the convergence of cognitive, emotional, and communicative components, and is influenced by sociocultural factors as well as specific family characteristics, including family type, culture, and the frequency and quality of intrafamilial communication. The review demonstrates that both formal and non-formal education programmes can cognitively and emotionally empower students, enabling them to become potential agents of change and reinforcing the spillover effect within the family. Especially when parents are systematically involved in such programs, the benefits of IGL are maximized for all participants. It can be argued that IGL is reinforced when three key conditions are met:

-

The presence of explicit environmental education that enhances the child’s knowledge and self-efficacy,

-

Emotional connectedness and an open, dialogic family communication style, and

-

The design of participatory interventions that actively engage both generations.

The review substantiates that future research in this area should include larger and more culturally diverse samples, adopt longitudinal designs, and utilize mixed-method approaches. Importantly, the design of educational interventions should move beyond short-term or fragmented initiatives and aim for longer-duration programs. These should combine experiential involvement of both students and parents with consistent follow-up, in order to better understand the underlying mechanisms of IGL and to capture its long-term impacts.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to express his thankfulness to the reviewers, for their comments and suggestions that improved the presentation of this study.

Funding: No funding source is reported for this study.

Ethical statement: The author stated that ethical approval is not required. The study does not involve the collection of primary data and relies solely on already published material.

AI statement: The authors stated that no generative AI or AI based tools were used in this literature review.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the author.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the author.

References

- Abeliotis, K., Goussia-Rizou, M., Sdrali, D., & Vassiloudis, I. (2010). How parents report their environmental attitudes: A case study from Greece. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12, 329-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9197-0

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alexander, P. A. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: The art and science of quality systematic reviews. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 6-23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319854352

- Amin, M. S., Permanasari, A., & Setiabudi, A. (2019). The pattern of environmental education practice at schools and its impact to the level of environmental literacy of school-age student. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 245(1), Article 012029. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/245/1/012029

- Ardoin, N. M., & Bowers, A. W. (2020). Early childhood environmental education: A systematic review of the research literature. Educational Research Review, 31, Article 100353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353

- Bevan, J. L., Murphy, M. K., Lannutti, P. J., Slatcher, R. B., & Balzarini, R. N. (2023). A descriptive literature review of early research on COVID-19 and close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(1), 201-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221115387

- Boudet, H., Ardoin, N. M., Flora, J., Armel, K. C., Desai, M., & Robinson, T. N. (2016). Effects of a behaviour change intervention for Girl Scouts on child and parent energy-saving behaviours. Nature Energy, 1, Article 16091. https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.91

- Brakovska, V., & Blumberga, A. (2024). The influence of young people on household decisions on energy efficiency in Latvia. Environmental and Climate Technologies, 28(1), 45-57. https://doi.org/10.2478/rtuect-2024-0005

- Brown, I. (2018). Assessing climate change risks to the natural environment to facilitate cross-sectoral adaptation policy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2125), Article 20170297. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0297

- Casaló, L. V., & Escario, J.-J. (2016). Intergenerational association of environmental concern: Evidence of parents’ and children’s concern. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.09.001

- Chen, F., Zhang, T., Hou, J., Chen, H., Long, R., & Zhang, T. (2025). How do children encourage their parents to adopt green consumption behaviour? - An analysis of the perspective of moral elevation. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 55, 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2025.02.024

- Chineka, R., & Yasukawa, K. (2020). Intergenerational learning in climate change adaptations; limitations and affordances. Environmental Education Research, 26(4), 577-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1733494

- Delmas, M. A., Giottonini, P., & Teng, G. (2024). Adolescents as energy conservation stewards. Sustainable Environment, 10(1), Article 2408926. https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2024.2408926

- Denault, A.-S., Bouchard, M., Proulx, J., Poulin, F., Dupéré, V., Archambault, I., & Lavoie, M. D. (2024). Predictors of pro-environmental behaviors in adolescence: A scoping review. Sustainability, 16(13), Article 5383. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135383

- Deng, J., Tang, J., Lu, C., Han, B., & Liu, P. (2022). Commitment and intergenerational influence: A field study on the role of children in promoting recycling in the family. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 185, Article 106403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106403

- Ding, M., Liu, X., & Liu, P. (2024). Parent-child environmental interaction promotes pro-environmental behaviors through family well-being: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Current Psychology, 43, 16476-16488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05495-z

- Eberbach, C., & Crowley, K. (2017). From seeing to observing: How parents and children learn to see science in a botanical garden. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(4), 608-642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1308867

- Eisenmenger, N., Pichler, D. M., Krenmayr, N., Noll, D., Plank, B., Schalmann, E., Wandl, M.-T., & Gingrich, S. (2020). The sustainable development goals prioritize economic growth over sustainable resource use: A critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective. Sustainability Science, 15, 1101-1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00813-x

- Fang, W.-T., Hassan, A., & LePage, B. A. (2023). Environmental literacy. In The living environmental education. Sustainable development goal series. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4234-1_4

- Firmansyah, D., & Saepuloh, D. (2022). Social learning theory: Cognitive and behavioral approaches. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Holistik, 1(3), 297-324.

- Fitzpatrick, A., & Halpenny, A. M. (2023). Intergenerational learning as a pedagogical strategy in early childhood education services: Perspectives from an Irish study. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 31(4), 512-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2022.2153259

- Flurry, L. A., & Burns, A. C. (2005). Children’s influence in purchase decisions: A social power theory approach. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.08.007

- Gentina, E., & Singh, P. (2015). How national culture and parental style affect the process of adolescents’ ecological resocialization. Sustainability, 7(6), 7581-7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7067581

- Giancola, M., Pino, M. C., Zacheo, C., Sannino, M., & D’Amico, S. (2024). The intergenerational transmission of pro-environmental behaviours: The role of moral judgment in primary school-age children. Social Sciences, 13(6), Article 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13060318

- Gill, C., & Lang, C. (2018). Learn to conserve: The effects of in-school energy education on at-home electricity consumption. Energy Policy, 118, 88-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.03.058

- Gilleran Stephens, C., Short, A., & Linnane, S. (2023). H2O heroes: Adding value to an environmental education outreach programme through intergenerational learning. Irish Educational Studies, 42(2), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1932549

- Granados-Sánchez, J. (2023). Sustainable global citizenship: A critical realist approach. Social Sciences, 12(3), Article 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030171

- Grob, A. (1995). A structural model of environmental attitudes and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90004-7

- Guan, W., & Geng, L. (2024). Intergenerational influence on children’s pro-environmental behaviors: Exploring the roles of psychological richness and mindful parenting. Personality and Individual Differences, 229, Article 112778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112778

- Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 433-448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9323-z

- Harada, T., Shoji, M., & Takafuji, Y. (2023). Intergenerational spillover effects of school-based disaster education: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 85, Article 103505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103505

- Hartley, J. M., Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Busch, K. C., Carrier, S. J., DeMattia, E. A., Jambeck, J. R., Lawson, D. F., & Strnad, R. L. (2021). Intergenerational learning: A recommendation for engaging youth to address marine debris challenges. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 170, Article 112648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112648

- Hill, R. J. (2012). Civic engagement and environmental literacy. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2012(135), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20025

- Hines, J. M., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1987). Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Education, 18(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1987.9943482

- Hungerford, H. R., & Peyton, R. B. (1977). A paradigm of environmental action (ERIC Document ED137116). ERIC Document Services.

- Istead, L., & Shapiro, B. (2014). Recognizing the child as knowledgeable other: Intergenerational learning research to consider child-to-adult influence on parent and family eco-knowledge. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28(1), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2013.851751

- Jaime, M., Salazar, C., Alpizar, F., & Carlsson, F. (2023). Can school environmental education programs make children and parents more pro-environmental? Journal of Development Economics, 161, Article 103032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.103032

- Jia, F., & Yu, H. (2021). Action, communication, and engagement: How parents “ACE” children’s pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, Article 101575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101575

- Kalyanasundaram, M., Ando, Y., & Asari, M. (2024). The intergenerational learning effects of a home study program for elementary and junior high school children on knowledge and awareness of plastic consumption. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 26, 2242-2253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-024-01962-2

- Kong, X., & Jia, F. (2023). Intergenerational transmission of environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior: A dyadic relationship. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 89, Article 102058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102058

- Lawson, D. F., Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Carrier, S. J., Strnad, R., & Seekamp, E. (2018). Intergenerational learning: Are children key in spurring climate action? Global Environmental Change, 53, 204-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.002

- Lawson, D. F., Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Carrier, S. J., Seekamp, E., & Strnad, R. (2019). Evaluating climate change behaviors and concern in the family context. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 678-690. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1564248

- Liu, J., & Green, R. J. (2024). Children’s pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic review of the literature. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 205, Article 107524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107524

- Liu, J., Chen, Q., & Dang, J. (2022). New intergenerational evidence on reverse socialization of environmental literacy. Sustainability Science, 17, 2543-2555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01194-z

- Liu, X., & Kaida, N. (2024). Parent-child intergenerational associations of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and pro-environmental behaviors in Japan and China. Sustainability, 16(23), Article 10445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310445

- Luetz, J. M., & Walid, M. (2019). Social responsibility versus sustainable development in United Nations policy documents: A meta-analytical review of key terms in Human Development Reports. In W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Social responsibility and sustainability (World Sustainability Series, pp. 301-334). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03562-4_16

- MacGregor, J. C., Oliver, C. L., MacQuarrie, B. J., & Wathen, C. N. (2021). Intimate partner violence and work: A scoping review of published research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 717-727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019881746

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, Article n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Parth, S., Schickl, M., Keller, L., & Stoetter, J. (2020). Quality child–parent relationships and their impact on intergenerational learning and multiplier effects in climate change education: Are we bridging the knowledge–action gap? Sustainability, 12(17), Article 7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177030

- Pearce, H., Hudders, L., & Van de Sompel, D. (2020). Young energy savers: Exploring the role of parents, peers, media and schools in saving energy among children in Belgium. Energy Research & Social Science, 63, Article 101392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101392

- Pekez, J., Stojanov, J., Mihajlovic, V., Marceta, U., Radovanovic, L., Palinkas, I., & Vujic, B. (2025). The impact analysis of education on raising awareness towards climate change and energy efficiency. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 35, 41-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-024-09904-7

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887.fmatter

- Queiroz, P., Garcia, O. F., Garcia, F., Zacares, J. J., & Camino, C. (2020). Self and nature: Parental socialization, self-esteem, and environmental values in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), Article 3732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103732

- Ríos-Ramírez, P. (2023). Formal and non-formal education in the teaching-learning process. Revista Transdisciplinaria de Estudios Sociales y Tecnológicos, 3(3), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.58594/rtest.v3i3.90

- Roth, C. E. (1992). Environmental literacy: Its roots, evolution and directions in the 1990s. ERIC.

- Salazar, C., Jaime, M., Leiva, M., & González, N. (2022). From theory to action: Explaining the process of knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the use and disposal of plastic among school children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 80, Article 101777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101777

- Saltan, F., & Divarci, O. F. (2017). Using blogs to improve elementary school students’ environmental literacy in science class. European Journal of Educational Research, 6(3), 347-355. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.6.3.347

- Sihvonen, P., Lappalainen, R., Herranen, J., & Aksela, M. (2024). Promoting sustainability together with parents in early childhood education. Education Sciences, 14(5), Article 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050541

- Singh, P., Sahadev, S., Oates, C. J., & Alevizou, P. (2020). Pro-environmental behavior in families: A reverse socialization perspective. Journal of Business Research, 115, 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.047

- Spiteri, J. (2020). Too young to know? A multiple case study of child-to-parent intergenerational learning in relation to environmental sustainability. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 14(1), 61-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408220934649

- Spiteri, J. (2023). Approaches to foster young children’s engagement with climate action: A scoping review. Sustainability, 15(19), Article 14604. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914604

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 81-97.

- Straub, C. L., & Leahy, J. E. (2017). Intergenerational environmental communication: Child influence on parent environmental knowledge and behavior. Natural Sciences Education, 46(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2016.06.0018

- Suryatna, Y. (2023). Education sustainability development in the effectiveness of parents’ role to build students’ competence. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 14(2), 118-141.

- Tian, J., Gong, Y., Li, Y., Sun, Y., & Chen, X. (2023). Children-led environmental communication fosters their own and parents’ conservation behavior. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 42, 322-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.10.006

- Trujillo-Torres, J. M., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., Mentado-Labao, T., & Barrera-Corominas, A. (2023). Intergenerational learning and its impact on the improvement of educational processes: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 13(10), Article 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13101019

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802

- Vassiloudis, I. (2024). Can primary school pupils become researchers? A research project on the accessibility of public spaces. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 20(3), Article e2414. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/14693

- Wang, Y., Xu, H., Xu, X., & Zhou, Y. (2025). The power of children in energy conservation: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Development Economics, 174, Article 103439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2024.103439

- Wang, Z., & Li, W. (2024). The mechanism of adolescent environmental passion influencing parent pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 96, Article 102342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102342

- Williams, S., McEwen, L. J., & Quinn, N. (2017). As the climate changes: Intergenerational action-based learning in relation to flood education. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(3), 154-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2016.1256261

- Woelfel, J. (1972). Significant others and their role relationships to students in a high school population. Rural Sociology, 37(1), 86-97.

- Xia, W., & Li, L. M. W. (2022). Multilevel evidence for the parent-adolescent dyadic effect of familiarity with climate change on pro-environmental behaviors in 14 societies: Moderating effects of societal power distance and individualism. Environment and Behavior, 54(7-8), 1097-1132. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139165221129550

- Zhang, T., Chen, F., Gu, X., Li, Z., & Zhu, Z. (2025). How education from children influences parents’ green travel behavior? The mediating role of environmental protection commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, Article 1532152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1532152

- Zhong, S., Cheng, Q., Zhang, S., Huang, C., & Wang, Z. (2021). An impact assessment of disaster education on children’s flood risk perceptions in China: Policy implications for adaptation to climate extremes. Science of the Total Environment, 757, Article 143761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143761

- Zhou, M. Y., & Brown, D. (2017). Educational learning theories (2nd ed.). GALILEO Open Learning Materials, Dalton State College. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=education-textbooks

- Zimmerman, H. T., & McClain, L. R. (2015). Family learning outdoors: Guided participation on a nature walk. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53(6), 919-942. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21254

- Žukauskienė, R., Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I., Gabė, V., & Kaniušonytė, G. (2021). “My words matter”: The role of adolescents in changing pro-environmental habits in the family. Environment and Behavior, 53(10), 1140-1162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916520953150

How to cite this article

APA

Vassiloudis, I. (2026). Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

Vancouver

Vassiloudis I. Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1):e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

AMA

Vassiloudis I. Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1), e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

Chicago

Vassiloudis, Ioannis. "Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 1 (2026): e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

Harvard

Vassiloudis, I. (2026). Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

MLA

Vassiloudis, Ioannis "Intergenerational learning for the environment and the sustainability: A systematic literature review". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2026, e2602. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17500

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)