Abstract

Scientific argumentation has been a much-studied topic in the research literature; however, the evidence predominantly focuses on the assimilation of scientific concepts through textual analysis. This study seeks to extend the discourse by examining how learners generate scientific evidence after working with a web-based global climate change simulation. Seventy undergraduate participants completed measures of pre-existing knowledge, then engaged in the simulation, and answered open-ended outcome questions where they substantiated their answers with evidence. Results supported the contention that evidence generated explicitly from the simulation was of a higher caliber in both its clarity and relevance. Moreover, the findings suggest that the influence of prior knowledge offered minimal effect on the quality of the evidence provided, irrespective of whether the evidence was informed by the simulation or not. This suggests that the immersive and interactive nature of the simulation supported the development of nuanced understanding and scientific evidence among learners.

Keywords

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2601

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

Publication date: 01 Jan 2026

Online publication date: 03 Dec 2025

Article Views: 654

Article Downloads: 370

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

A long-standing goal of the modern science education reform movement has been increasing the use of evidence in making arguments about scientific issues (National Research Council, 1996; NGSS Lead States, 2013; Rutherford & Ahlgren, 1991). There have been an increasing number of studies of late examining public understanding of contested and often misunderstood scientific issues where researchers have focused on individuals’ views on topics ranging from genetically modified organisms, vaccines, to modern industrial farming (e.g., Bromme & Goldman, 2014; Feinstein, 2015; Nisbet, 2009; Sinatra et al., 2014; Streefland, 2001). Much of this work has focused on how the public understands and interprets science as mediated through existing background knowledge and epistemic belief systems. Such questions were mostly investigated through empirical studies that used text to examine participants’ conceptual change on the contested scientific issues. However, there is scarce evidence of how the public interprets science or how prior knowledge and epistemic beliefs may influence conceptual understanding while interacting with scientific evidence in simulated, web-based activities, which provide different learning experiences from receiving information textually, as a reader. Therefore, we aim supplement this research by examining how students use prior understanding and/or new evidence generated using simulated empirical activities. This study will examine/investigate how undergraduate students used evidence to support their views on the contested issue of global climate change after being immersed in a dynamic web-based simulation experience.

This study centers on participants’ views on the causes of climate change (i.e., strictly naturally caused, strictly human-caused, or a combination of both) and the evidence used to support their arguments. We were interested in whether the source of this evidence (i.e., from the simulation or from their prior knowledge) changed the nature of their arguments and evidence, as opposed to interventions that used text to affect knowledge or beliefs about climate change. In our mixed-methods analysis, we examined how (or whether) participants used evidence to support a scientific claim after working with a climate change simulator and the substance of this evidence.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

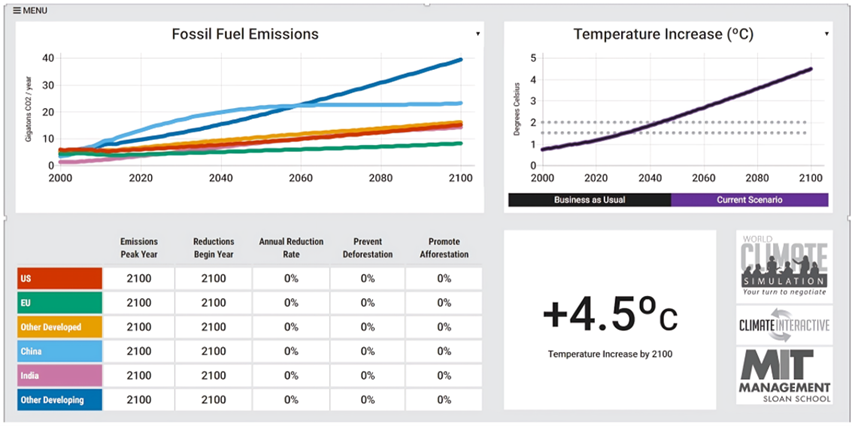

A central focus of this study is on changes to learners’ conceptual understanding of science and the use of evidence during this change. This framework required an explicit examination of student ideas about scientific concepts and the rationale or justification for these ideas to have a better grasp of their learning (Hewson et al., 1998). Much of what we know about students’ understanding of controversial science topics has been through the lenses of models of conceptual change, such as the cognitive reconstruction of knowledge model (Dole & Sinatra, 1998). However, much of the focus on research using these models has been on the use of text in facilitating students’ understanding of science (e.g., Sinatra & Broughton, 2011), rather than activities that require students to engage in more scientific processes (e.g., generating and interpreting data, generating research questions) as they would in a dynamic and immersive simulated experience. While there have been studies about climate change in secondary and post-secondary science classrooms (e.g., Lombardi & Sinatra, 2012; Lombardi et al., 2012); there have been few studies in the area of open-ended, dynamic web-based simulation experiences among students with varying degrees of background knowledge and interest in science. The interactive simulation activities provide different learning experiences from traditional ways of learning, such as reading and lectures. By contrast, students have the opportunity to directly interact with scientific evidence, rather than being passive receivers of information. For example, by adjusting the level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while controlling other contributing factors in the web-based simulator, students can view, both numerically and graphically, the resulting changes to temperature and sea level. The data output based on these adjustments can be seen in the Figure 1. By engaging in these interactive experiences, students can test the conclusions or descriptions from textbooks or lectures on their own, as well as gaining a fine-grained understanding of the topic, such as the unique effect of each contributing factor on the whole system. It is likely that such interactive experiences would impact students’ interpretation of the scientific evidence in aspects that are critical to conceptual change, including coherency, plausibility, credibility, and comprehensibility while improving their ability to draw on evidence in their arugmentation (Dole & Sinatra, 1998).

Further, studies reporting the benefits of using simulations tend to report positive findings regarding student learning (e.g., Chao et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2014) but are limited in how they examine argumentation with controversial topics. McElhaney and Linn (2011) reported positive connections between effective student experimental strategy use within simulations and learning outcomes regarding kinematics. However, the learning outcome assessment/tasks in this study focused on participants’ interpretations of static, researcher-created data and problem sets, as opposed to unique, participant induced evidence they generated through iterative and dynamic exploration of complex systems in a simulated environment.

To expand this area of research, we drew upon Sinatra et al.’s (2014) notion of the dimensions of epistemic cognition. Our focus in this study was the justification (i.e., how relevant and clear the claims were) and source (i.e., where the evidence came from, which might include data generated from the news or a college course) dimensions of this framework. Within this framework, justification is critical for students’ understanding of these topics because this provides the evidence for why they hold their scientific beliefs. Two important aspects of justification are the relevance of that justification and the clarity of that justification. Relevance refers to how closely aligned the cited evidence was for a claim related to climate change. For example, a relevant piece of evidence related to climate change might include data on increasing fossil fuel use over the past century, while an irrelevant piece of evidence might include a discussion of the ozone layer, or seasons. Clarity refers to evidence that was supported by the scientific consensus and claims that are logical and accurate. For example, a clear piece of evidence related to climate may include discussion of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels as it correlates with an increasing mean global air temperature, while an unclear piece of evidence related to climate change might be related to increasing human consumption of resources, without making the connection to the consumption with fossil fuels and resulting climate consequences.

The other focus on students’ use of evidence highlights the sources of the evidence presented. When reading a text and being asked to provide scientific evidence, a logical source of evidence would come directly from the given text (Bråten et al., 2014). There is evidence to suggest that the types of texts (e.g., informational and persuasive) change how students process the text (e.g., Dinsmore et al., 2015) and how the quality of the assessed learning outcomes differ (Eason et al., 2012). However, there is a dearth of evidence related to how an interactive, web-based simulation might influence which evidence, whether from the simulation or their prior knowledge is relied on more.

Third, questions remain as to how the source of evidence relates to the resulting clarity and relevance of said evidence. In our study, we were interested in determining whether dynamic, web-based simulations provide students with the kinds of empirical experiences that help support them develop this evidence. By experiencing simulated climate change models that include data for students to examine and toggle in real-time, we believe that students’ evidence-based arguments about the causes of climate change will help them better justify their beliefs. Additionally, we wanted to determine whether their prior scientific or conceptual understanding influenced the clarity and relevance of their arguments.

To summarize, the current study aims to provide empirical evidence on how engaging in dynamic, web-based simulations contributes to the quality of students’ use of scientific evidence and argumentation. The quality of students’ use of scientific evidence is operationally defined as clarity and relevance of the justification evidence in students’ argumentation. In considering how these activities provide engaging and comprehensive learning experiences that are likely to contribute to conceptual change, we believe that the quality of evidence generated and used from such activities would be higher than from other sources, such as prior knowledge. In addition, we are also interested in the extent to which prior knowledge is related to the quality of students’ use of scientific evidence after participation in the simulation activities.

From this proposition, two hypotheses can be formed. First, prior knowledge could be a significant, positive predictor of the quality of evidence use. It is likely that students with more prior knowledge of the scientific topic would score higher on the quality of evidence usage considering their advantage of knowing more about the topic initially. The other plausible hypothesis is that prior knowledge might not be a significant predictor because it is probable that participants would rely mostly on the simulation activities that they recently undertook when citing evidence in their argumentation, thus introducing the discounting for prior knowledge as a vital source of information. Our research questions for this study were:

-

Do the clarity and relevance of evidence used to discuss the cause(s) of climate change differ depending on whether the evidence was generated based on information directly from the simulation or information from participants’ prior knowledge that was not presented in the simulation?

-

How does individuals’ prior knowledge of climate change before participation in the climate simulation influence the clarity and relevance of the evidence they present after their participation in the climate simulation?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A critical component of this study was the online climate simulation called C-LEARN (https://www.climateinteractive.org/tools/c-learn/simulation/). This simulation allowed users to adjust climate inputs to find the impacts from these inputs included possible changes in atmospheric CO2 levels, temperature, and sea level and could be viewed numerically and graphed in relation to current conditions, as well as impact goals defined by the Paris agreement–an international agreement designed to mediate climate change (e.g., Rogelj et al., 2012). The inputs that users could manipulate included GHG emissions of developed and developing countries, reductions of these GHG emissions, and amount of deforestation (destruction of forests) and afforestation (establishment of a forest) in real-time scenarios.

Seventy undergraduate participants were recruited from multiple biology and education courses from a mid-sized university in the southeastern United States to sample students with varied levels of interest and prior knowledge in climate science. Participants were mostly female (65.7%), Caucasian (68.1%), and from an assortment of majors including physical/life sciences (52.9%), education (43.3%), and the social sciences (10%) with an average age of 22.86 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.63) and an average grade point average of 3.22 (SD = .37).

Prior to engaging in the climate simulator, participants completed instruments that measured demographics, general interest in science topics, and knowledge of climate change phenomena. During the simulation, participants were asked to think aloud for 30 minutes as they engaged in the simulated learning activities and then prompted to respond to three open-ended questions. Since only the prior knowledge and open-ended outcome questions are important to the current study, descriptions of the other variables (i.e., interest and strategic processing) are not included but are described fully in a separate paper (Dinsmore & Zoelllner, 2017).

Regarding prior knowledge, 18 items were given to measure participants’ domain and topic knowledge using a graduated response model (Alexander et al., 1998). Items for the measure were sourced from science textbooks (e.g., Woodhead, 2001) and online resources (e.g., NASA global climate change website). This measure contained four levels of possible responses including: an in-domain correct response (C), an in-domain incorrect response (IDI), an out-of-domain incorrect response (ODI), and folklore incorrect response (F). Below is a sample item from the measure:

The most effective GHG at trapping heat near the surface of the Earth is as follows:

-

Water vapor (C)

-

Hotbed gases (F)

-

Carbon dioxide (IDI)

-

Oxygen (ODI)

Correct responses were scored a 4, IDI responses were scored a 2, ODI responses were

scored a 1, and folklore responses were scored a 0. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of these items yielded a one-factor solution explaining 12.85% of the total variance with excellent latent reliability (H = .80; Hancock & Mueller, 2001). Analyses conducted used factor scores derived from this EFA.

Regarding the outcome questions, each participant answered three outcome questions:

-

Do you think planetary climate change occurs naturally or is caused by humans? Please provide as much evidence for your answer as you can.

-

Did your interactions with the science simulator help you answer this question, and if so, how?

-

Were there any specific strategies you used during the science simulation that helped you answer the first questions about whether climate change was natural or caused by humans?

Only question one was used in this analysis, however, question two was used to provide additional validation for the source coding described subsequently.

We coded their responses to question one with schemes related to source of the evidence, the clarity of the evidence, and the relevance of the cited cause of climate change described in Table 1. When examining for source, evidence was coded for whether it came from the simulation (e.g., a reference to data generated from the simulation) or came from someplace else (e.g., the news, a college course).

Table 1. Coding scheme for question 1 regarding source, clarity, and relevance of evidence

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Additionally, evidence was coded for its clarity. Clear responses were supported by the scientific consensus and logic. An example of this category can be seen below:

Through the usage of oxygen, production of CO2 and heavy reliance on fossil fuels, it would be unreasonable to assume humans didn’t contribute in some way, shape, or form to the change in the earth’s climate.

Responses were coded as “unclear” if they were not supported with a clear connection to evidence or were inaccurate. An example of an “unclear” response was: “I think that plants and animals also have an impact and that it is not all just humans even though they may be the largest contributing factor.” In this case, the participants were vague about the nature of the impact of plants, animals, and humans on climate. Finally, responses were coded for how the evidence participants used was related to climate change. Those coded “relevant” made strong connections between the evidence and their claims. Participant statements that were not directly relevant to climate change were coded “out of context.” An example of this kind of response was:

Climate change is natural as well but not is such drastic amounts over such a short period of time. Thinking in only 100 years our oceans will not be basic or neutral, but slightly acidic.

While there may be some accuracy in this response, the evidence presented is not directly related to the causes of climate change.

Interrater reliability for source (k = .64), clarity (k = .60), and relevance (k = .56) were all acceptable, ranging from moderate to substantial agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977) across 21% of the total sample. Any disagreements were discussed and rectified in a conference between the first and second authors.

RESULTS

Analyses of these data commenced on 112 pieces of evidence across 63 participants (7 of the participants did not provide any evidence in their outcome response and thus were not included). Total numbers and percentages of each code category are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Number of percentage of codes in each code category

|

Clarity and relevance of evidence generated. Regarding research question one–the relevance and clarity of evidence generated from the simulation versus their prior knowledge–analyses indicated that evidence generated from the simulation was both clearer and more relevant. Specifically, evidence generated from the simulation was more likely to result in clear (r = .26, p < .01) and relevant (r = .20, p = .03) evidence. For instance, participant 16 said, “Based on the simulation, changing the amount of deforestation/afforestation really changed the amount of CO2 emission and abundance in the atmosphere”, which was coded as explicitly from the simulation, clear, and relevant, while Participant 48 said, “I think that it is also naturally done in the environment, that this planet goes through phases just as we go through seasons”, which was coded as not from the simulation, unclear, and out of context. These results are strong evidence that the source of evidence matters regarding the justification (i.e., clarity and relevance) of that evidence. Significantly, use of evidence that was directly linked to engagement in the climate simulation more often led to evidence that was clear and relevant as opposed to evidence that could not be directly linked to the engagement in the climate simulation. Thus, engagement in the simulation had a positive effect on participants’ ability to engage in effective argumentation about this controversial science topic.

Influence of participants’ prior knowledge on the clarity and relevance of their evidence generated from the simulation. Regarding research question two–the influence of prior knowledge on participants’ use of evidence–these data did not support a significant or even moderate effect for prior knowledge on either the source or justification (i.e., clarity or relevance) of their evidence. Correlations and 95% confidence intervals between prior knowledge, source, prior knowledge for evidence sourced from the simulation to clarity and relevance, and prior knowledge for evidence sourced not from the simulation to clarity and relevance are displayed in Table 3. Notably, none of the relations between prior knowledge, source, relevance, or clarity contained confidence intervals that did not include zero. For example, for evidence that was and was not sourced directly from the science simulation, prior knowledge related to the relevance of that evidence not at all or weakly (rs of -.02 and .094, respectively). While power could be an issue given the relatively small size, there was relevant power in this analysis (n = 85; β = .8) to detect a moderate effect size (r = .30). Given the critical role–and large effect–of prior knowledge in both reading outcomes more generally (e.g., Hall, 1989; McNamara & Kintsch, 1996) and the role of prior knowledge on the overall complexity of the structure of these participants’ outcomes reported elsewhere (Dinsmore & Zoelllner, 2017), the lack of moderate or large and significant effects for prior knowledge were quite striking.

Table 3. Correlations and 95% confidence intervals between prior knowledge, source, and justification of evidence

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This analysis appears to support Sinatra et al.’s (2014) dimensions of epistemic cognition, specifically the justification and source dimensions of the framework. Our findings suggests that an open-ended, student-driven simulation experience can serve to enhance the quality of the evidence that students can draw upon to justify their claims. Additionally, we see this analysis as an important first step in developing further instructional scaffolds to encourage learners to develop evidence directly from the simulation as a source, rather than relying strictly on their prior knowledge or other sources, which resulted in lower quality evidence in this study.

The results provide substantial evidence that science simulations can facilitate learners’ generation of evidence that is both clearer and more relevant than that from other sources (e.g., prior knowledge), when those learners make scientific arguments. Consistent with other studies on the use of simulations in science learning (Chao et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2014), the current study added to the literature and supported that simulation-based activities provide opportunities for learners to interact with the learning content in a systematic and autonomous way, which can translate to a positive effect on learning. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to explore the effect of simulation-based activities on student use of science evidence. Clearly, there are still many important questions to investigate in this area. First, it is worth exploring the comparative effect of simulation-based over text-based activities on student interpretation, generation, and evaluation of science evidence. Future studies could investigate whether and under what circumstances engaging in science simulations has an advantage over text reading (e.g., use of refutation text), the more traditional way of facilitating conceptual change (Sinatra & Broughton, 2011), in improving student use of qualitative science evidence. These and related studies may deepen our current understanding of the cognitive processes enacted while engaging with controversial topics. Moreover, it is also important to learn about the optimization of integrated simulation-based activities into classroom instruction when teaching controversial science topics. Considering the unique advantages of simulation-based activities, including intuitive presentation of evidence and flexible manipulation of individual components of a science topic, they possess great potential to further enhance the effect of evidence-based science instructions, such as model-based instruction (Chinn & Buckland, 2012) and instruction that promotes critical evaluation (Lombardi et al., 2013).

Additionally, the quality of evidence (i.e., clarity and relevance) generated from this science simulation does not appear to rely on learners’ prior knowledge as with other instructional scaffolds such as reading. This finding suggests that students with various levels of prior knowledge tend to rely solely on the simulation in the search for evidence about a controversial science topic. This noteworthy finding offers insights into both teaching practices and future research agendas. These data indicate that simulations can help students use higher quality evidence in their argumentation, even if they lack background knowledge in climate change. In this way, a simulation such as the C-Learn simulator can serve as an instructional scaffold that students can engage independently to build the quality of their scientific argumentation skills, even those with less prior knowledge to leverage. Used as a stand-alone intervention or in conjunction with instruction, the simulation appears to support a stronger public understanding of science with citizens of varying interests and knowledge of climate change as the world faces it effects. From a research standpoint, it is worth exploring the unique characteristics of simulation-based learning experience compared to traditional classroom activities (e.g., reading comprehension) that may explain the different roles that prior knowledge plays in student science learning. In future studies, examining other cognitive abilities that are more closely related to real-time information processing, such as executive functioning, could add clarity to this intriguing phenomenon.

Author contributions: BPZ: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing; DDD: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; HZ: data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; XR: conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. All authors agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: No funding source is reported for this study.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that the project was reviewed by the University of North Florida Institutional Review Board and approved for human subject research. IRB Reference Number 16-038. Written informed consents were obtained from the participants.

AI statement: The authors stated that there was no use of AI on this project.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Alexander, P. A., Murphy, P. K., & Kulikowich, J. M. (1998). What responses to domain-specific analogy problems reveal about emerging competence: A new perspective on an old acquaintance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 397-406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.3.397

- Bråten, I., Ferguson, L. E., Strømsø, H. I., & Anmarkrud, Ø. (2014). Students working with multiple conflicting documents on a scientific issue: Relations between epistemic cognition while reading and sourcing and argumentation in essays. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(1), 58-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12005

- Bromme, R., & Goldman, S.R. (2014). The public’s bounded understanding of science. Educational Psychologist, 49(2), 59-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.921572

- Chao, J., Chiu, J. L., DeJaegher, C. J., & Pan, E. A. (2016). Sensor-augmented virtual labs: Using physical interactions with science simulations to promote understanding of gas behavior. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(1), 16-33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-015-9574-4

- Chen, S., Chang, W.-H., Lai, C.-H., & Tsai, C.-Y. (2014). A comparison of students’ approaches to inquiry, conceptual learning, and attitudes in simulation-based and microcomputer-based laboratories. Science Education, 98(5), 905-935. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21126

- Chinn, C. A., & Buckland, L. A. (2012). Model-based instruction: Fostering change in evolutionary conceptions and in epistemic practices. In E. M. Evans, G. M. Sinatra, K. S. Rosengren, & S. K. Brem (Eds.), Evolution challenges: Integrating research and practice in teaching and learning about evolution (pp. 211-233). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199730421.003.0010

- Dinsmore, D. L., Loughlin, S. M., Parkinson, M. M., & Alexander, P. A. (2015). The effects of persuasive and expository text on metacognitive monitoring and control. Learning and Individual Differences, 38, 54-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.01009

- Dinsmore, D. L., & Zoellner, B. P. (2017). The relation between cognitive and metacognitive strategic processing during science simulations. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(1), 95-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12177

- Dole, J. A., & Sinatra, G. M. (1998). Reconceptualizing change in the cognitive construction of knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 33(2/3), 109-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1998.9653294

- Eason, S. H., Goldberg, L. F., Young, K. M., Geist, M. C., & Cutting, L. E. (2012). Reader-text interactions: How differential text and question types influence cognitive skills needed for reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 515-528. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027182

- Feinstein, N. W. (2015). Education, communication, and science in the public sphere. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(2), 145-163. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21192

- Hall, W. S. (1989). Reading comprehension. American Psychologist, 44(2), 157-161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.157

- Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2001). Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems. In R. Cudeck, S. du Toit, & D. Sorbom (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: Present and future–A Festschrift in honor of Karl Joreskog. Scientific Software International, Inc.

- Hewson, P. W., Beeth, M. E., & Thorley, N. R. (1998). Teaching for conceptual change. In B. J. Fraser, K. G. Tobin, & C. J. McRobbie (Eds.), International handbook of science education (pp. 199-218). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4940-2_13

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Lombardi, D., & Sinatra, G. M. (2012). College students’ perceptions about the plausibility of human-induced climate change. Research in Science Education, 42(2), 201-217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-010-9196-z

- Lombardi, D., Sinatra, G. M., & Nussbaum, E. M. (2013). Plausibility reappraisals and shifts in middle school students’ climate change conceptions. Learning and Instruction, 27, 50-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.03.001

- McElhaney, K. W., & Linn, M. C. (2011). Investigations of a complex, realistic task: Intentional, unsystematic, and exhaustive experimenters. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(7), 745-770. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20423

- McNamara, D. S., & Kintsch, W. (1996). Learning from texts: Effects of prior knowledge and text coherence. Discourse Processes, 22(3), 247-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539609544975

- National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. National Academies Press.

- NGSS Lead States. (2013). Next generation science standards: For states, by states. The National Academies Press.

- Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12-23. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

- Rogelj, J., Meinshausen, M., & Knutti, R. (2012). Global warming under old and new scenarios using IPCC climate sensitivity range estimates. Nature Climate Change, 2(4), 248-253. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1385

- Rutherford, F. J., & Ahlgren, A. (1991). Science for all Americans. Oxford University Press.

- Sinatra, G. M., & Broughton, S. H. (2011). Bridging reading comprehension and conceptual change in science education: The promise of refutation text. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(4), 374-393. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.005

- Sinatra, G. M., Kienhues, D., & Hofer, B. K. (2014). Addressing challenges to public understanding of science: Epistemic cognition, motivated reasoning, and conceptual change. Educational Psychologist, 49(2), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.916216

- Streefland, P. H. (2001). Public doubts about vaccination safety and resistance against vaccination. Health Policy, 55(3), 159-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00132-9

- Woodhead, J. A. (2001). Earth science: The physics and chemistry of earth. Salem Press.

How to cite this article

APA

Zoellner, B. P., Dinsmore, D. D., Zhao, H., & Rozas, X. (2026). Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

Vancouver

Zoellner BP, Dinsmore DD, Zhao H, Rozas X. Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1):e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

AMA

Zoellner BP, Dinsmore DD, Zhao H, Rozas X. Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1), e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

Chicago

Zoellner, Brian P., Daniel D. Dinsmore, Hongyang Zhao, and Xavier Rozas. "Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 1 (2026): e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

Harvard

Zoellner, B. P., Dinsmore, D. D., Zhao, H., and Rozas, X. (2026). Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

MLA

Zoellner, Brian P. et al. "Using a global climate change simulation to develop students’ use of quality scientific evidence and argumentation". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2026, e2601. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17499

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)