Abstract

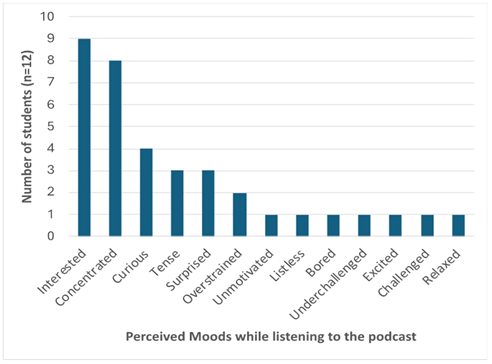

Unlike video, podcasts have not been widely used as a learning medium in science education in schools. At the same time, podcasts are a part of many students’ daily lives and offer opportunities for motivating learning environments. Numerous well-produced and accessible knowledge podcasts are readily available on streaming platforms. The question arises as to how students view learning with such knowledge podcasts in the classroom. In this exploratory study, students in three eighth grade classes in Hamburg, Germany used excerpts from a podcast about climate change as a learning tool in science class for gaining information related to experiments, they had to do. Guided interviews were conducted with 12 students. Results show that students were generally very positive about their experience using the podcasts, as they describe their mood, while using the podcast as “interested”, “focused”, and “curious”. Overall, they rated the specific podcast used as understandable and helpful but criticized the lack of fit with the content of the lesson. Students also expressed conditions for successful learning with podcasts, such as the social form of teaching and type of work assignments. The students emphasized that they would like podcasts to be used as an additional method for learning in science classes, rather than podcasts just replacing reading textbooks or teacher explanations. In the future, integrating podcasts thoughtfully into science education has the potential to enrich students’ learning experiences, although further research is needed to optimize their implementation in science classrooms.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 2, 2026, Article No: e2611

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

Publication date: 01 Apr 2026

Online publication date: 18 Feb 2026

Article Views: 22

Article Downloads: 14

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

Podcasts are a widespread format–in Germany 70% of young people generally use podcasts and 27% of young people use them regularly (Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest [MPFS], 2024). In the USA, the trend is similar: two-thirds of individuals aged 12 to 36 years listen to podcasts at least monthly, with numbers steadily increasing (MarketingCharts, 2025). Furthermore, the availability of podcasts continues to grow, especially in the area of science knowledge. The number of professionally produced podcasts on topics such as anthropogenic climate change, a highly relevant scientific issue, is expanding (MacKenzie, 2019). These podcasts could serve as important learning resources, as they are easily accessible, and education for sustainable development is one of the key strategies to combat climate change (see SDG 4; United Nations, 2015).

In times of increasing digitalization, learning in schools should be supported through various digital media formats and thereby activate and motivate students. Podcasts as a learning medium offer the possibility of individualized learning, allowing flexible use at one’s own pace. However, the effectiveness of podcasts as a learning medium in the context of science education has hardly been investigated. When podcasts are used in the classroom, it is usually as a learning product of students (e.g., Torrau & Gloe, 2021) or in language-based subjects (e.g., Calero Ramírez, 2011). Therefore, its potential in science education as a learning medium, for example as an alternative to a teacher’s explanation or a video, remains largely unknown. Especially within the complex context of climate change, professionally produced podcasts can serve as a valuable additional resource for teachers. This exploratory study seeks to identify the potentials and limitations of podcasts as a learning medium in science education from students’ perspectives and to contribute to the didactic discussion on digital media formats in science teaching. The podcast used in this study focuses on the physical background of climate change and its effects.

THEORY

This section provides a structured theoretical foundation for understanding the educational potential of podcasts. It begins with a general overview of podcasts, followed by an exploration of relevant learning theories that underpin their pedagogical use. Building on this theoretical basis, the focus shifts to methods of implementing podcasts in educational contexts. Subsequently, podcasts are examined more specifically as a learning medium, highlighting their unique characteristics. The section concludes by outlining the opportunities podcasts offer for enhancing learning processes across various educational settings.

Podcasts have gained increasing popularity and accessibility over the recent years. A podcast is generally defined as an episodic series of spoken-word digital audio files distributed via the internet and designed for on-demand consumption at the listener’s convenience. Therefore, as a medium, podcasting content–unlike live radio broadcasts–is not tied to a schedule. In addition, because of low barriers for production, almost anyone can create and share a podcast (Andok, 2025; Rime et al., 2022). This raises the question, as to how professionally produced podcasts can be distinguished from amateur productions.

To our knowledge, there are no peer-reviewed quality criteria specific to podcasts in the field of media research that could be used to distinguish amateur podcasts from professionally produced podcasts. Assuming that professional podcasts are characterized by their fulfillment of quality criteria, we have therefore drawn on the framework developed by Lazzari and Betella (2007) for high-quality podcasting environments. This framework, which focuses on the environment as a whole, allows us to identify a number of quality criteria for podcasts. According to this framework, professional podcasts should fulfill the following criteria:

-

Recording quality: The podcast should be recorded in sufficient quality (e.g., quality of microphones).

-

Editing quality: The podcast should be edited to a sufficient standard (e.g., filtering and mixing of voices; musical background).

-

Content quality: The content of the podcast should be complete, credible, coherent and presented to an appropriate extent, and should be relevant to the target audience.

-

Communication quality: The style of the podcast should be appropriate for the target audience in terms of format, style, pronunciation and clarity.

The last two criteria are particularly interesting for the design of the podcast, as they address the content level of the podcast and require the medium to be appropriate for the target audience.

In the area of professionally produced podcasts, Drew (2017) published a framework to divide educational podcasts into three subgenres: “The quick burst”, a tightly time-controlled podcast genre (1-5 minutes), that delivers a single learning tip or key idea in a highly compressed format, making it suitable as a supplemental tool for warm-ups, summaries, or re-engagement. “The narrative”, a genre characterized by extended, monologic storytelling (40-80 minutes), that blends radio-like episodicity with the immersive narrative voice of audiobooks, enabling learners to construct coherent, longitudinal understandings of complex topics. And “The chat show”: this genre is organized around institutionalized, topic-focused conversation between hosts (and guests), using dialogue to model disciplinary discourse practices and support higher-order thinking such as analysis, synthesis, and critical evaluation. Pedagogically, it integrates an intentional blend of humor and intellectual engagement as a cognitive and affective scaffold to make abstract concepts more accessible, enhance memorability, and strengthen learners’ emotional and conceptual connection to scientific content.

Mayer (2008) developed the cognitive theory of multimedia learning (CTML), which has been used as a guiding framework for producing educational podcasts (McNamara & Drew, 2019). The CTML is based on cognitive load theory (CLT) (Sweller, 1988) and outlines three fundamental elements: first, the existence of two distinct cognitive channels–namely, a visual and a verbal channel; second, the idea of limited capacity within these channels; and third, that deep learning relies on active processes engaged by the learner (Mayer, 2008). Mayer (2008) offers ten principles for effective multimedia instruction. Two of these principles highlight the potential of podcasts as a learning medium: the principle of modality, which emphasizes presenting words as spoken text rather than printed text, and the principle of personalization, which advocates for delivering words in a conversational style rather than in a formal tone. Accordingly, podcasts are particularly valuable because they utilize spoken words (aligned with the principle of modality), and their conversational style contrasts with the more formal tone of teacher explanations or textbooks (aligned with the principle of personalization).

Moreno’s (2007) cognitive-affective theory of learning with media incorporates an affective component into the CTML, which helps prevent cognitive factors from dominating exclusively. Using this theory as a foundation, one can examine how motivation and emotional factors influence learning through media tools. Following are a few examples on how this theory may help us to understand the potential effects podcasts can have on student motivation:

-

In the case of many podcasts, their conversational style–described by Drew (2017) as a genre called “The chat show”–has the potential to contextualize metalanguage within everyday language, thereby positively affecting students’ motivation and supporting their learning process.

-

Moreover, since podcasts are such a well known medium among students, they are familiar with the format from their everyday lives. Therefore, the use of podcasts as a learning medium reflects the digital environment in which young people live. This familiarity can enhance student motivation when podcasts are incorporated into classroom instruction (Calero Ramirez, 2011).

On the other hand, based on CTML, there are some considerations that may favor videos as a preferred format over podcasts. Mayer (2008) advocates for presenting words alongside pictures rather than without them. When content on the visual and auditory levels are aligned (Mayer & Moreno, 2003), an instructional video that combines explanations with visuals would generally be a better choice than a podcast alone on the auditory level, based on Mayer’s (2008) rationale. However, it is also important to note that, compared to instructional videos, podcasts allow learners to allocate more of their visual resources to other tasks while listening, since both channels (visual and auditory) have limited capacity, in accordance with CLT (Chandler & Sweller, 1991). This distribution of cognitive resources enables learners to multitask effectively–for instance, students can take notes without missing out on visual content while listening to a podcast.

Another important theory for learning through the use of podcasts is the learning styles theory (Fleming, 2001; Fleming & Mills, 1992). This theory describes individuals as having different preferred modalities for learning. Four main types are distinguished: visual (V), auditory (A), read/write (R), and kinesthetic (K). As a consequence, each learner has different preferences regarding media formats, which influence their choice of learning tools (Kohler & Dietrich, 2021). It can be assumed that learners with an auditory preference benefit most from using podcasts as a learning resource, as they tend to learn effectively through environments such as listening to lectures or participating in group discussions (Fleming & Mills, 1992). To foster inclusive learning environments, it is important to offer a variety of media tools that engage different modalities, thus acknowledging the diverse learning styles present among students. Since podcasts are underrepresented in classrooms compared to educational videos or texts, this presents a significant potential for development. Recently, podcasts have been discussed as an effective educational resource for teachers working with children who have visual impairments (McNamara et al., 2024).

When looking at classrooms, the usage of digital media and its positive impact on students has been widely recognized. For example, in terms of student motivation, teachers utilize videos, which students can watch at their own pace, as a learning medium to serve as an effective alternative to traditional teacher explanations or explanatory texts. Students also often use explanatory videos when doing homework or preparing for an exam (Labude et al., 2024). Podcasts in classrooms, as another example for digital media, can be implemented as a student-generated learning product as well as a professionally produced learning medium: For the former, there are studies that examine this method empirically and in the context of climate change. In a study by Torrau & Gloe (2021), students developed a podcast on whether climate change is the direct cause of forest fires in Australia. As part of the project, students developed a deep understanding of the logics in different societal subsystems (e.g., media, science, and politics) and on how the legitimacy of scientific knowledge is challenged by the politicization of media coverage of climate change. Gullino et al. (2023) highlight the potential of student podcasting in the context of placemaking or urban design. Students were able to demonstrate new sustainable solutions in urban planning in communicative learning environments and to make their new knowledge visible to others in open access podcasts. Based on the previously discussed learning theories, one can assume that using this teaching approach for podcasts as a digital medium has the opportunity to result in increased student motivation and a more positive attitude towards the subject, compared to traditional teaching approaches (Hillmayr et al., 2017). Ahlbach (2022) highlights that creating podcasts as a learning product is expected to result in greater learning gains for students than simply listening to podcasts. However, students creating podcasts demands a considerable amount of time.

The second form of using podcasts in the classroom, where already available (professionally produced) podcasts are used as a learning medium for students, can be found in foreign language classrooms. For example, podcasts are used to train listening comprehension in German as a foreign language classes in a study by Calero Ramirez (2011). This study showed that podcasts have advantages over traditional listening comprehension formats, such as a high degree of authenticity and timeliness of the material. Panagiotidis (2021) describes the use of podcasts to overcome psychological barriers to language learning that arise because learners get into a flow where they forget that they are in a learning situation.

This approach as well may lead to a more positive attitude towards the subject compared to traditional teaching approaches (Hillmayr et al., 2017). One rather time-consuming way of using already produced podcasts in class is the method of developing a podcast as a teacher, as Wolpaw and Harvey (2020) instruct. The more economic method would be to use professionally produced podcasts as a learning medium. This method could become an everyday method of explaining a subject in science classes in the long term.

However, we are not aware of any study in a science education context that examines professionally produced podcasts as a learning medium for teaching science for secondary school students (grade 5 to grade 12). Studies for a science context can only be found for higher education. For example, Lee and Chan (2007) show that podcasts can create a sense of belonging in distance learning and increase understanding of content. Zacharis (2012) suggests that when podcasts are used as a learning tool, perceived ease of use and perceived enjoyment contribute to greater learning success. Wolpaw et al. (2022) support this finding, indicating that medical university students experience greater learning success when using podcasts compared to a group that learned using textbooks. Scutter et al. (2010) show that students report a positive effect on their learning progress after using podcasts as a substitute for an on-site lecture, but doubt that this is active learning. They conclude that short excerpts from podcasts may be more appropriate for active learning. Sutton-Brady et al. (2009) report that students in a podcast trial at their university appreciated the brevity of the podcasts and that the podcasts contained only information that was relevant to them. In a nutshell, podcasts in higher education can boost students’ sense of belonging and understanding, with learning gains linked to ease of use and enjoyment. However, to support active learning, evidence points to using short, relevant excerpts rather than long lecture replacements. However, it remains unclear to what extent any of these findings may be transferable to the use of podcasts in science education at secondary schools.

The use of professionally produced podcasts in science education might also support dealing with heterogeneity as well as with climate education: When building on individual learning prerequisites (e.g., existing prior knowledge), a crucial predictor of successful teaching and learning processes is considered. In a heterogeneous student population, the individualization of learning processes is a central component of teaching (Breidenstein, 2013; Bohl et al., 2023). We assume that podcasts as a learning medium can be used to promote individualized learning by allowing students to use the audio material flexibly in terms of content and at their own pace when working on learning opportunities. Passages of the podcast can be replayed at any time. We see particular opportunities for this individualization in the current design of learning spaces in schools, which increasingly allow for more individualized learning.

Another significant potential of professionally produced podcasts lies in enhancing climate education. An informed public about climate change is extremely important for tackling the climate crisis (Hung, 2022). There is a strong correlation between educated knowledge about climate change and individual awareness of the problem (Taddicken et al., 2018) and acceptance of the problem (Ranney & Clark, 2016). However, the level of climate literacy in society is rather low, both internationally and nationally, and it is particularly concerning that only around 12% of people are aware of the time and pressure to act in the climate context (Allianz Research, 2021). Enhancing climate education in schools might be one key to leveraging the knowledge about climate change in the public. However, when dealing with climate change as an interdisciplinary and complex topic, many teachers do not feel adequately prepared to teach about climate change, as interdisciplinary topics like this are often not comprehensively covered in teacher training (Johnson et al., 2008). Therefore, it might be beneficial for teachers to rely on ready-made explanations provided by experts or science communicators (Johnson et al., 2008).

This goes along with students having many technically inappropriate ideas about climate change, such as the hole in the ozone layer as a cause of climate change (Niebert & Gropengiesser, 2013). Other preconceptions relate to key learning contents such as the greenhouse effect and the carbon cycle (Düsing et al., 2019; Jarrett & Takacs, 2020). To address these preconceptions meaningfully, it is essential to teach in an engaging and effective manner. The use of podcasts as a learning medium offers a promising opportunity to achieve this goal. From a didactic perspective, it is therefore also important to examine students’ perspectives on lessons that incorporate podcasts. This research interest forms the basis of the following research question in the project “climate physics in podcasts”:

Research question: What are students’ perspectives on the use of a podcast on climate change as a learning medium in science classrooms?

METHODS

The study design we present in the following was ethically approved by our local institution on educational monitoring and quality development. The educational podcast used in our project, “Jetzt mal ganz in Ruhe–Klima-Physik und sonst nix” (“Let’s take it easy–Climate physics and that’s it”; short: “Let’s take it easy”; Büker et al., 2024-2025), was developed and produced by three experienced podcasters and science journalists. A total of 12 double episodes were produced, each dealing with one aspect of anthropogenic climate change (e.g., greenhouse effect, combustion, energy, oceans). The focus of the podcast is to present the physics content in a way that is accessible to a lay audience. The three speakers incorporate typical podcast elements such as a question-and-answer format, repetitions and summaries, as well as an informal tone and humor.

Based upon our understanding of what differentiates a professional podcast from an amateur podcast, this podcast fulfills all four criteria for being a professional podcast, that targets the interested public. Moreover, in the framework of Drew (2017), the podcast can be categorized as “The chat show”.

Our research interest emerged from a study initially conceived in line with design-based research (Design-Based Research Collective, 2003), in which researchers and teachers from schools in Hamburg, Germany, would collaboratively design and implement lessons that integrated episodes of the podcast “Let’s take it easy” in varied ways. During the early stages of the project, we refined this plan in response to emerging considerations regarding how podcasts are perceived and used by learners. To establish a robust empirical basis for subsequent design decisions, we therefore adopted an exploratory focus on students’ perspectives on podcasts as a learning medium. As a result, the use of podcast episodes was less tightly coupled to specific lesson content and classroom tasks than it would have been in a fully podcast-centered unit; however, this approach enabled a more targeted examination of students’ perspectives.

Sample generation was conducted in collaboration with a German high school in Hamburg (social index: 5). The Hamburg social index characterizes the socio-economic composition of a school’s student body on a scale from 1 to 6, where 1 indicates schools with particularly underprivileged socio-economic backgrounds and 6 indicates schools where students predominantly come from privileged socio-economic backgrounds. During the survey period, the school combined the science lessons1 of their 8th grade classes into a four-week project-based lesson. The aim of this was to enable the students to experimentally investigate questions of their own choice in an open learning environment. The students worked in small groups of up to three and dealt in depth with one of the contexts climate change, energy, or soil. For this purpose, they had access to a set of pre-selected experiments, which they used to develop and work on their own research questions; they were supported in this by their teachers.

The groups that chose the contexts of climate change or energy were relevant for the research project, as the podcast “Let’s take it easy” offers information on these topics in several episodes. From these groups, the researchers selected those whose research questions matched the content of individual podcast episodes (e.g., sea level rise in the context of climate change), while groups without a suitable podcast reference (e.g., hydrogen in the context of energy) were excluded. All students from the selected groups who agreed to participate were included in the sample, so that ultimately \(n = 12\) 8th grade students (8 female and 4 male) aged between 13 and 14 years took part in the study. In line with the exploratory study design, no further characteristics of the participants were collected.

Once the groups of the sample settled on a set of research questions and experiments, the researchers supported them with matching chapters from episodes of the podcast “Let’s take it easy”. For example, students studying sea level rise were given the chapters “Seas are filling and rising” and “Rising sea levels then and now” from the episode “We love oceans” to listen to. The students listened to the podcast as a support, e.g., to learn more about the theoretical background of the experiments they chose. The researchers ensured that the selected chapters were appropriately matched in length, with the total duration not exceeding 20 minutes. Suiting the open and experimental design of our study, the students were given no restrictions on how to listen to the podcast. This resulted in some groups changing place to the hallway, where they listened to the podcast as a group via a speaker, while other groups split up for listening to the podcast and used headphones, to listen to the podcast on their own.

To answer the research question, guided 15-20 minutes interviews were conducted after students were using the podcast and were working on their given task. The interview guide aimed to capture the students’ perspectives on the use of podcasts in science education. In order to capture the students’ thinking as authentically as possible, questions were asked in a narrowing order, starting off with open-ended questions and concluding with closed-ended questions. Table 1 shows an overview of the questions.

Table 1. Main questions of the interview guide

|

The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed, anonymized, and subsequently analyzed using qualitative, content-analytical, and descriptive quantitative methods. For the qualitative content analysis, a deductive-inductive category system was developed in accordance with Mayring (2015) (see Table 2). Students’ statements were assigned to one of the three main categories–”podcast”, “lesson and teaching”, or “self”–based on the core content of each statement. The category “podcast” includes statements regarding the characteristics of the specific climate change podcast as well as general comments on podcasts as a learning tool. “Lesson and teaching” encompasses statements about how the podcast was integrated into the lesson, including the setting, exercises, and interconnection of content. “Self” covers statements related to perceived progress and the learning process resulting from using the podcast. Each statement was also assigned to one of the subcategories, “rewarding learning experiences” or “challenging learning experiences.” All main and subcategories are deductive, except for the category “general opportunities and challenges” and its subcategories, which emerged inductively from the data.

Table 2. Coding system used to analyze the transcribed interview data

|

First, part of the data was independently coded by both authors, following a discursive exchange to achieve a shared understanding of the individual categories as well as the inductively added category “general opportunities and challenges.” Subsequently, each author independently coded half of the dataset. The validity of the category system was confirmed through independent double coding of 28% of the data (based on the number of codes across all documents) by both authors, resulting in an intercoder reliability of \(\kappa = 0.92\) (Brennan & Prediger, 1981).

Several anonymized student statements were translated from German into English for publication in this article. The translations were performed manually by both authors, with the assistance of an online translator to clarify the meaning of individual words when necessary.

RESULTS

Overall Impression: Students’ Perceptions of Their Own Mood When Learning With the “Let’s Take It Easy” Climate Change Podcast

Overall, the surveyed students expressed a positive attitude toward the use of podcasts in science education and rated their use as an educational tool in the classroom as beneficial. The most frequently reported moods as answers were “interested”, “focused”, and “curious”. All moods, along with the number of students who selected each, are shown in Figure 1. Some students reported listening to podcasts in their everyday lives, which sparked their interest. In particular, the unfamiliarity of podcasts in a school context sparked the students’ interest (Table 3).

Table 3. Student 04’s quote

|

Additionally, three students selected “tense” as the mood, though this tension was not caused by the podcast itself, but rather by external circumstances, as evidenced by the statement in Table 4.

Table 4. Student 07’s quote

|

Beyond sharing their moods, the students expressed their views on the podcast, the classroom environment, and their reflections on their own learning. The results derived from the qualitative content analysis using the category system in Table 2 are summarized in Table 5 and will be discussed in the three subsequent paragraphs, each focused on one main category.

Table 5. Summary of results of the qualitative content analysis (each bullet point represents a paraphrased student perspective from the interviews & the number in square brackets indicates how many students expressed this perspective and the number in round brackets represents how often the perspective was mentioned overall)

|

Students’ Perspectives on the Characteristics of Podcasts Used as a Learning Medium (Podcast Category)

Podcasts were regarded as fundamentally different from traditional teaching methods and were especially appreciated as supplementary aids for explaining content. Students justified this preference by saying that listening is a welcome change from frequent reading of textbook material. The following quote illustrates that, in addition to cognitive factors, affective aspects are also involved when listening to podcasts in classroom (Table 6).

Table 6. Student 11’s quote

|

On the other hand, the podcast speakers represent a change from the teacher, who is typically responsible for explaining new topics. This change can exert a positive motivational influence. Furthermore, the conversational, “The chat show”-like character of the podcast may have an immersive effect by embedding scientific context into everyday conversational situations, as evidenced by the statement from a student in Table 7.

Table 7. Student 09’s quote-1

|

Some students felt that a visual element to support learning was missing, as they are accustomed to listening and seeing in educational videos. However, some students did not see the purely auditory format as a disadvantage. They reported that they could concentrate better on the podcast than on videos (Table 8).

Table 8. Student 01’s quote

|

Most students rated the specific podcast “Let’s take it easy” very positively. The clear and vivid explanations and clear narrative structure were the most frequently highlighted aspects. Some students elaborated on their comments about The narrative structure, praising recurring elements such as questions, summaries, and repetitions. They said these elements made understanding complex content, like the climate change, easier.

Students also mentioned several points that contributed to challenging learning experiences. One recurring obstacle was listening to individual chapters of the podcast instead of listening to an entire episode. Several students said this made it harder to understand the references and cross-references in the podcast. One student found the roles of the three speakers unclear and wished for an introduction. Additionally, some students found the technical explanations insufficiently comprehensible. They justified this by saying that the podcast used many unfamiliar technical terms or was spoken too quickly (Table 9).

Table 9. Student 09’s quote-2

|

Some comments addressed the opportunities and challenges of podcasts in the classroom in general rather than referring to the specific podcast, “Let’s take it easy”. Some students said that having a visual element, such as explanatory videos, would have helped them learn. At the same time, other students said that podcasts, in comparison to learning videos, are a new and unusual learning medium that sparks their interest compared to more conventional learning media.

Students’ Perspectives on Organizational Aspects of Lessons With Podcast (Lesson and Teaching Category)

Almost all of the students agreed that successful learning requires a high degree of alignment between classroom assignments and podcast content. However, they were divided on whether this applied to the podcast “Let’s take it easy”. Some students found the podcast helpful for class tasks, while others felt the content was not relevant enough. The majority, however, criticized the lack of relevance between the podcast content and the material covered in class. One student expressed the sentiment in Table 10.

Table 10. Student 10’s quote

|

On the other hand, some students recognized the advantage of controlling their own learning process while listening to the podcast. Since rushing during learning impedes deep understanding, having the opportunity to take more time and listen repeatedly is valuable. This sense of self-control also manifests as reduced dependence on the teacher’s explanations, as explained in the student quote in Table 11.

Table 11. Student 05’s quote-1

|

Several students found it conducive to learning that they could listen to the podcast alone instead of in a group. Some students felt that the group setting did not allow them to follow the podcast attentively. They noted that it was difficult to concentrate. This is illustrated by the statement in Table 12.

Table 12. Student 06’s quote

|

However, other students appreciate the opportunity to exchange ideas with each other. They used this opportunity to explain subject-specific content to one another (Table 13).

Table 13. Student 05’s quote-2

|

The students proposed a variety of ideas on how to organize learning with podcasts to ensure a fruitful learning process. Several students expressed a desire for accompanying tasks to be available alongside the podcast, helping them engage with the content in a more targeted manner. Their ideas also included completing tasks concurrently while listening to the podcast. Some students felt that listening to entire 30-minute episodes made more sense but that this would be difficult to implement in a school context. The students’ ideas also revealed that some felt rushed and wished they had more time to engage with the podcast.

Students’ Perspectives on Their Own Requirements for Learning With Podcasts (Self Category)

Most students perceived their working attitude as focused when using the podcast. For these students, this perception was closely linked to their interest in the podcast’s content. Their interest was also partly fueled by the novelty of the podcast medium as a learning tool, which encouraged attentive listening. Additionally, some students reported that the podcast sparked their curiosity about a topic, motivating them to explore it more deeply by using the internet as a resource for further research.

The interviews also revealed that students employed various listening strategies to learn effectively with the podcast. Some students stopped the podcast to discuss ambiguities in small groups, while others rewound to re-listen to certain sections (Table 14).

Table 14. Student 03’s quote

|

Finally, the students reflected on the prerequisites for successfully learning with podcasts. In addition to having a personal interest in the topic and sufficient prior knowledge, they identified the learning environment as particularly crucial. Some students stated that they were more easily distracted while listening than when watching videos and emphasized the need for a quiet environment.

DISCUSSION

Similar to other studies on podcasts in an educational context, our research confirms that podcasts can motivate learners. This result aligns with findings in higher education, where podcasts were used as a learning medium. The secondary school students in our study reported that the climate change podcast “Let’s take it easy” piqued their interest and had a motivating effect on their learning. Compared to educational videos, which are already well-established and popular among students, students see podcasts as having both advantages and disadvantages. All in all, students support the idea of incorporating podcasts as a supplementary learning tool, rather than viewing them as a substitute for educational videos or in-class explanations by teachers. This idea emphasizes the importance of engaging as many modalities as possible by incorporating various media formats as learning tools that stimulate different cognitive channels. Such an approach helps make learning more accessible and inclusive for all students. The observation that some students missed the visual component while others preferred to gain information exclusively through the auditory channel matches the implications of the learning styles theory (Fleming, 2001; Fleming & Mills, 1992). By adding podcasts to the array of available media tools, the range of addressed learning preferences is further broadened, promoting a more varied and inclusive learning experience.

Overall, the climate change podcast “Let’s take it easy” received very positive feedback. The students particularly appreciated the elements that distinctly identify the podcast as a “The chat show” (Drew, 2017), such as the conversational format of asking and answering questions. There are also indications that the podcast appeals to students on an affective-emotional level–another characteristic of the “The chat show”-format–such as student 09’s comment that the podcasters appeared happy, funny, and less formal than a typical teacher.

Students reported that, in many cases, they were able to learn and understand complex subject-specific contexts of the podcast. This aligns with previous research findings, which indicate that listening to podcasts can have a positive learning impact among college and university students compared to learning in lectures and with textbooks (e.g., Wolpaw et al., 2022). However, it became evident that the podcast placed very high demands on many students’ concentration, sometimes bordering on overwhelming. This was primarily due to the use of unfamiliar technical terms. Therefore, it is essential to tailor the podcast as closely as possible to students’ prior knowledge. However, since the selection of knowledge podcasts is not infinite, this cannot always be guaranteed. As a result, alternative solutions must be explored. One option could be to create a glossary that defines key technical terms.

The students emphasized the importance of a quiet learning environment for meaningful engagement with the podcast. Students working alone expressed a preference to listen privately in the future to avoid potential distractions from others. Conversely, students working in groups benefited from taking breaks to clarify confusing passages or technical terms with their peers. This raises the question of how school settings can facilitate a quiet atmosphere for listening to podcasts while also providing sufficient space for collaborative learning. Innovative room concepts may hold the key to addressing this challenge.

Students demonstrated the use of comprehension strategies, such as rewinding, slowing down the playback speed, and pausing the podcast, independently and without explicit instruction. They perceived these strategies as helpful and conducive to understanding. According to Zacharis (2012), ease of use is a key factor in supporting learning with podcasts, and this appears to be fulfilled among the students. The concept of enhancing individualized and autonomous learning experiences through podcasts seems feasible, given that students are able to navigate and employ these strategies, even without prior instruction.

Rather than positioning the podcast “Let’s take it easy” as the central instructional resource, we adopted a curriculum-compatible integration strategy that enabled its use within established classroom structures. Specifically, selected episodes were incorporated into a four-week climate change project implemented in three eighth-grade classes. Because this project emphasized student-led inquiry and independent work on self-generated questions, the podcast primarily served as an impulse and contextual resource. This approach resulted in a less tightly specified thematic coupling between podcast content and classroom tasks than a fully podcast-centered unit would have afforded; however, it increased feasibility and maintained coherence with the project’s inquiry-oriented design. Notwithstanding this loose alignment, students’ feedback was overwhelmingly positive, underscoring the pedagogical potential of podcasts and supporting the goal of integrating the medium more systematically into teaching in future research.

However, the students’ statements make it clear that lessons should be closely aligned with the podcast’s content. Rather than an open learning environment, the students in our study preferred a guided approach to task completion while listening to the podcast. This may be an artifact of the project-based teaching approach, which may have caused uncertainty among the students. Additionally, the students requested an introduction to the podcast and its format. They also criticized the cross-references to other podcast content, which they could not understand because they only listened to few excerpts. These results raise the question of whether it would be necessary to produce podcasts especially for schools, where there are, for example, no cross references made during the individual episodes. Alternatively, this aspect could serve as a criterion for teachers to evaluate the suitability of podcasts for classroom use, although obtaining information about cross-references in a time-efficient manner might be challenging. A simpler approach could be to distribute episode guides to students and introduce each speaker along with their role in the podcast prior to listening. In some cases, episode guides are already available directly on the podcast’s description or caption on streaming platforms.

Overall, the individual interviews with students provided qualitative insights into their perspectives on learning with podcasts in the classroom. The interview guide was an effective way to encourage students to share their thoughts. However, the method has its limitations. Due to social desirability bias, students may respond in a way they think the interviewer will find favorable. As a result, their answers regarding the podcast may be positively biased. Additionally, we assume that students might have downplayed their difficulties in understanding the content of the podcast, since such challenges often become more apparent only after more specific questions from the interviewer. This could lead to an under representation of thoughts indicating that students feel overwhelmed by the content. Additionally, our sample size is small, and although it provides exploratory qualitative insights, these cannot easily be generalized to other students. Another limitation is that we focused only on one podcast that deals with the topic of climate change. Other podcasts, that might have a different style to Drew’s (2017) scheme or deal with topics that remain purely within the scientific discipline and do not have such high social significance, might reveal different results.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

In summary, students in our study consider podcasts to be a valuable learning tool in science education. Students are interested in using podcasts in the future, provided that two conditions are met: the content must be relevant to the topics and assignments being studied in class; and second, the learning environment must facilitate focused listening (while still providing opportunities for collaborative learning). From students’ perspective, podcasts serve as a meaningful complement to traditional teaching methods rather than a substitute. The findings highlight the podcast’s potential to increase students’ motivation for deep engagement with complex subject matter in the context of climate change. However, further research is necessary to systematically explore and evaluate different usage scenarios from a didactic perspective. Specifically, future studies should investigate how teachers select appropriate podcasts for their lessons. Developing supporting materials to accompany the podcasts is another issue that warrants further investigation. While podcasts have the potential to ease lesson planning and execution, they also introduce some uncertainties. One possible approach to address this challenge is to incorporate podcast training into teacher education programs (Goldman, 2018). Additionally, podcast developers should consider the extent to which their content aligns with the needs and expectations of a school-based audience. More future projects like this, which involve collaboration between science podcasters and science educators, can help pave the way toward more engaging and enriching learning experiences when integrating digital media into the classroom.

Author contributions: K Zilz & P Schuck: conceptualization, data curation, validation, formal analysis, and writing–review & editing & K Zilz: writing–original draft. Both authors agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: This study was funded by the German Federal Foundation for the Environment (Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt, DBU).

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Dietmar Höttecke for his initiative and idea for this study, as well as for securing the funding and Lena Rehberg for her valuable support with transcribing the interviews. The authors would also like to thank the podcasters Michael Büker, Johannes Kückens, and Jens Schröder, who provided valuable insights into the creation of science podcasts.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that the study was approved by the Institut für Bildungsmonitoring und Qualitätsentwicklung in Hamburg, Germany on 11 September 2024 with approval code 224-068. Written informed consents were obtained from the participants.

AI statement: The authors stated that generative AI tools were used only for language and style improvements.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

-

Typically, science education in Germany is organized into separate subjects such as biology, chemistry, physics, and geology↩︎

References

- Ahlbach, V. (2022). Das didaktische Potenzial von Podcasts im Sachunterricht [The didactical potential of podcasts in science lessons]. In M. Haider, & D. Schmeinck (Eds.), Digitalisierung in der Grundschule. Grundlagen, Gelingungsbedingungen und didaktische Konzeptionen am Beispiel des Fachs Sachunterricht (pp. 184-196). Klinkhardt. https://doi.org/10.35468/5938-14

- Allianz Research. (2021). Allianz climate literacy survey: Time to leave climate neverland. Euler Hermes. https://www.allianz.com/content/dam/onemarketing/azcom/Allianz_com/economic-research/publications/specials/en/2021/october/2021_10_27_Climate-literacy.pdf

- Andok, M. (2025). Podcast–The remediation of radio: A media theoretical framework for podcast research. Journalism and Media, 6(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010007

- Bohl, T., Budde, J., & Rieger-Ladich, M. (2023). Umgang mit Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht: Grundlagentheoretische Beiträge und didaktische Reflexionen [Dealing with heterogeneity in schools and teaching: Fundamental theoretical contributions and didactic reflections]. Klinkhardt. https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838559667

- Breidenstein, G. (2013). Die Individualisierung des Lernens unter den Bedingungen der Institution Schule [The individualization of learning under the conditions of the school institution]. In B. Kopp, S. Martschinke, M. Munser-Kiefer, M. Haider, E.-M. Kirschhock, G. Ranger, & G. Renner (Eds.), Individuelle Förderung und Lernen in der Gemeinschaft. Jahrbuch Grundschulforschung, vol 17 (pp. 35-50). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-04479-4_3

- Brennan, R. L., & Prediger, D. J. (1981). Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 41(3), 687-699. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448104100307

- Büker, M., Kückens, J., & Schröder, J. (2024-2025). Jetzt mal ganz in Ruhe–Klimaphysik und sonst nix [Let’s take it easy–Climate physics and that’s it]. Studio Feynstein. https://ganzinruhe.podigee.io/

- Calero Ramirez, C. D. C. (2011). Neue Medien im DaF-Unterricht: Theorie und Praxis zum Hörverstehenstraining mit podcasts [New media in German as a foreign language teaching: Theory and practice for listening comprehension training with podcasts]. Informationen Deutsch als Fremdsprache, 38(1), 36-69. https://doi.org/10.1515/infodaf-2011-0105

- Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293-332. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2

- Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5-8. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

- Drew, C. (2017). Educational podcasts: A genre analysis. E-Learning and Digital Media, 14(4), 201-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753017736177

- Düsing, K., Asshoff, R., & Hammann, M. (2019). Students’ conceptions of the carbon cycle: Identifying and interrelating components of the carbon cycle and tracing carbon atoms across the levels of biological organisation. Journal of Biological Education, 53(1), 110-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2018.1447002

- Fleming, N. D. (2001). Teaching and learning styles: VARK strategies. Z. Neil D.

- Fleming, N. D., & Mills, C. (1992). Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflection. To Improve the Academy, 11(1), 137-155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.1992.tb00213.x

- Goldman, T. (2018). The impact of podcasts in education. Pop Culture Intersections, 29.

- Gullino, S., Shtebunaev, S., & Wakerley, E. (2023). Podcasting and collaborative learning practices in placemaking studies. In L. Natarajan, & M. Short (Eds.), Engaged urban pedagogy. Participatory practices in planning and place-making (pp. 144-161). UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781800081239

- Hillmayr, D., Reinhold, F., Ziernwald, L., & Reiss, K. (2017). Digitale Medien im mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht der Sekundarstufe. Einsatzmöglichkeiten, Umsetzung und Wirksamkeit [Digital media in secondary school mathematics and science teaching. Possible applications, implementation, and effectiveness]. Waxmann.

- Hung, C. C. (2022). Climate change education. Knowing, doing and being. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003093800

- Jarrett, L., & Takacs, G. (2020). Secondary students’ ideas about scientific concepts underlying climate change. Environmental Education Research, 26(3), 400-420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1679092

- Johnson, R. M., Henderson, S., Gardiner, L., Russell, R., Ward, D., Foster, S., Meymaris, K., Hatheway, B., Carbone, L., & Eastburn, T. (2008). Lessons learned through our climate change professional development program for middle and high school teachers. Physical Geography, 29(6), 500-511. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3646.29.6.500

- Kohler, S., & Dietrich, T. C. (2021). Potentials and limitations of educational videos on YouTube for science communication. Frontiers in Communication, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.581302

- Labude, M., Vonschallen, S., Krüger, M., Schneider, C., & Metzger, S. (2024). Watch and learn: Wie Schüler: Innen und Lehrpersonen Erklärvideos für den Naturwissenschaftsunterricht nutzen [Watch and learn: How students and teachers use explanatory videos for science lessons]. Zeitschrift für Didaktik der Naturwissenschaften, 30(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40573-024-00172-5

- Lazzari, M., & Betella, A. (2007). Towards guidelines on educational podcasting quality: Problems arising from a real world experience. In M. J. Smith, & G. Salvendy (Eds), Human interface and the management of information. Interacting in information environments (pp. 404-412). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73354-6_44

- Lee, M. J., & Chan, A. (2007). Reducing the effects of isolation and promoting inclusivity for distance learners through podcasting. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 8(1), 85-105.

- MacKenzie, L. E. (2019). Science podcasts: Analysis of global production and output from 2004 to 2018. Royal Society Open Science, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180932

- MarketingCharts. (2025). Share of people who listen to podcasts on a monthly basis in the United States from 2020 to 2025, by age group. Statisca. https://www.statista.com/statistics/912381/united-states-monthly-podcast-listening-age/

- Mayer, R. E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, 63(8), 760-769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.63.8.760

- Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3801_6

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative content analysis. Fundamentals and techniques]. Beltz.

- McNamara, S., & Drew, C. (2019). Concept analysis of the theories used to develop educational podcasts. Educational Media International, 56(4), 300-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2019.1681107

- McNamara, S., Brian, A., Patey, M., & Bittner, M. (2024). Content acquisition podcasts vs open-access podcast: Improving preservice physical educators’ ability to teach students with visual impairments. Journal of Special Education Technology, 39(1), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/01626434231184820

- Moreno, R. (2007). Optimising learning from animations by minimising cognitive load: Cognitive and affective consequences of signalling and segmentation methods. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(6), 765-781. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1348

- MPFS. (2024). JIM–Studie 2024. Jugend, Information, Medien. Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger [JIM–Study 2024. Youth, information, media. Basic study on media use among 12- to 19-year-olds]. Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest. https://mpfs.de/app/uploads/2024/11/JIM_2024_PDF_barrierearm.pdf

- Niebert, K., & Gropengiesser, H. (2013). Understanding and communicating climate change in metaphors. Environmental Education Research, 19(3), 282-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.690855

- Panagiotidis, P. (2021). Podcasts in language learning. Research review and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN21 (pp. 10708-10717). https://doi.org/10.21125/edulearn.2021.2227

- Ranney, M. A., & Clark, D. (2016). Climate change conceptual change: Scientific information can transform attitudes. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 49-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12187

- Rime, J., Pike, C., & Collins, T. (2022). What is a podcast? Considering innovations in podcasting through the six-tensions framework. Convergence, 28(5), 1260-1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221104444

- Scutter, S., Stupans, I., Sawyer, T., & King, S. (2010). How do students use podcasts to support learning? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1089

- Sutton-Brady, C., Scott, K. M., Taylor, L., Carabetta, G., & Clark, S. (2009). The value of using short-format podcasts to enhance learning and teaching. Research in Learning Technology, 17(3), 219-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687760903247609

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

- Taddicken, M., Reif, A., & Hoppe, I. (2018). What do people know about climate change–And how confident are they? On measurements and analyses of science related knowledge. Journal of Science Communication, 17(3), Article A01. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.17030201

- Torrau, S., & Gloe, M. (2021). “Es sind nun mal leider keine Klimaaktivisten, die das Land führen”: Ungewissheit als Schüler*innenkategorie zu globalen Problemen [“Unfortunately, it’s not climate activists who are running the country”: Uncertainty as a category of students’ attitudes toward global problems]. Religionspädagogische Beiträge, 44(2), 127-139. https://doi.org/10.20377/rpb-149

- United Nations. (2015). The UN sustainable development goals. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Wolpaw, J. T., & Harvey, J. (2020). How to podcast: A great learning tool made simple. The Clinical Teacher, 17(2), 131-135. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13040

- Wolpaw, J., Ozsoy, S., Berenholtz, S., Wright, S., Bowen, K., Gogula, S., Lee, S., & Toy, S. (2022). A multimodal evaluation of podcast learning, retention, and electroencephalographically measured attention in medical trainees. Cureus, 14(11), Article e31289. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.31289

- Zacharis, N. Z. (2012). Predicting college students’ acceptance of podcasting as a learning tool. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 9(3), 171-183. https://doi.org/10.1108/17415651211258281

How to cite this article

APA

Zilz, K., & Schuck, P. (2026). Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(2), e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

Vancouver

Zilz K, Schuck P. Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(2):e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

AMA

Zilz K, Schuck P. Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(2), e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

Chicago

Zilz, Kendra, and Patrick Schuck. "Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 2 (2026): e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

Harvard

Zilz, K., and Schuck, P. (2026). Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(2), e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

MLA

Zilz, Kendra et al. "Students’ perspectives on using a science podcast on climate change as a learning tool". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 2, 2026, e2611. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17946

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)