Abstract

This study explores the incorporation of climate change into medical education by surveying about 700 students and 500 faculty at a Michigan medical school. One-way analysis of variance and post-hoc analysis assessed differences by role, age, and class year. Response rates were 9% and 8.4%. Findings show strong belief in human-induced climate change, especially among students (90%), and high concern about its effects. Both groups see climate change as a significant health issue and are willing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, opinions differ on integrating climate change strategies into medical practice, with students less likely than administrators to agree (41% vs. 52%, p < 0.05). Generational differences exist regarding emission reduction actions and including climate change strategies in medical practice. The study highlights the need for climate change education in medical curricula and calls for strategic planning, student advocacy, and tailored educational content.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2607

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

Publication date: 27 Jan 2026

Article Views: 153

Article Downloads: 91

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

Climate change is recognized as one of the most pressing challenges of our era (Climate Change, 2024). It has been linked to escalating climate-related disasters, affecting various aspects of human health. This includes an upsurge in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and a spectrum of neurological and psychological disorders (Haines & Patz, 2004; Rocque et al., 2021). Access to healthcare services has also become increasingly strained as climate events disrupt healthcare infrastructure and supply chains, leading to reduced availability of medical services and resources (Gamble et al., 2016; Salam et al., 2023). Both rural and urban communities are impacted by this rapidly growing issue, emphasizing the importance of targeted interventions (Zeleňáková, 2015). Furthermore, these health adversities disproportionately impact vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Gamble et al., 2016).

Recognizing the need to address the intersection of climate change and public health, there is a growing acknowledgment of the crucial role that healthcare professionals must play in responding to this multifaceted challenge (Kreslake et al., 2017). Despite this, healthcare professionals often lack the necessary understanding of how to address the health consequences of climate change (Kotcher et al., 2021; Sarfaty et al., 2016). A promising strategy to equip future healthcare providers with the necessary knowledge and skills is integrating climate change education into medical school curricula (Finkel, 2019). Yet, there is a notable lack of comprehensive data regarding the perspectives of medical school stakeholders–administrators and students–on climate change, its health implications, and the integration of related education into the curriculum. Understanding these attitudes is crucial for creating targeted educational interventions that enhance the medical community’s comprehension of climate change’s health impacts and the health system’s role in contributing to climate change (Lenzen et al., 2021; Wellbery et al., 2018).

This study examines the viewpoints of the administrators and students at a single institution regarding climate change, its implications for healthcare, and their readiness to integrate climate change education in the medical school curriculum. Including administration as part of the study population allows for a comprehensive understanding of institutional readiness and reservations regarding this topic. The insights gleaned from this study will lay the groundwork for crafting a climate change education framework at a single institution. Additionally, the findings have broader implications, potentially guiding the development of similar educational programs at other medical institutions.

METHODS

Population of Interest

The study focuses on medical students and administrators at a single institution. The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of administrators and students at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine (MSU CHM) on climate change education and its health implications.

Survey Development

The two surveys were developed referencing studies focusing on understanding perspectives on climate change and education initiatives (Moretti et al., 2023; Müller et al., 2023; Silverwood et al., 2024). The final student survey consisted of 20 questions while the administrators survey consisted of 21 questions. Questions were designed to assess interest and integration of climate change education into curricula, beliefs regarding climate change, and individuals’ perceptions on how climate change impacts clinical practice and patient care. Basic demographic information including participants’ gender, age, field of interest and geographic location was also collected. The survey was underwent review by two faculty advisors and received approval from the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board.

The survey was distributed to approximately 700 students and 500 administrators via email. Participants were allotted two months to complete the survey, during which time one additional reminder was sent. No incentives were used. The survey was administered through Qualtrics digital software Version XM ©2020 and all data collected was anonymized.

Data Analysis

The analyses were performed using the statistical software for the social sciences from IBM in Chicago, IL. For the analysis, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Summary statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, were computed to provide an overview of participant characteristics and question responses. Additionally, one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc analyses were used to examine the impact of role (administrators vs. students), age, and class year (M1, M2, M3, and M4) on survey responses.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

A total of 64 students and 42 faculty participated in the survey (response rates of 9% and 8%, respectively). Within the administrators’ survey, individuals were given the opportunity to indicate if they were part of faculty or administration. Notably, nine individuals identified themselves as part of administration, constituting 21% of the respondents, while the rest served as faculty (n = 33).

Among the student respondents, ages ranged from 22 to 62 years, with a mean age of approximately 29 years. A majority of the respondents (61%, n = 39) indicated that they have lived in Michigan the longest, suggesting that the sample predominantly consists of local students, reflective of the school’s overall student body population. Participants were distributed across different community campuses at MSU CHM, with a notable split between urban (84%, n = 53) and rural (16%, n = 10) settings. The academic representation included students from all years in medical school. Regarding specialty interests, the data showed a preference for Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, and Pediatrics, with other interests shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of the administrators, ages ranged from 29 to 86 years, with a mean age of approximately 52 years. The majority of respondents were based out of the East Lansing and Grand Rapids campuses at MSU CHM, with some at other community campuses including Flint, Southeast Michigan, and the Upper Peninsula. Most respondents (64%, n = 27) indicated Michigan as the state in which they lived the longest. The number of years that administrators have been part of the college ranged from 0 to 53 years, with 11 years as the average length of time. Within administrators, clinical and nonclinical faculty completed the survey. Their indicated specialties are shown in Table 1.

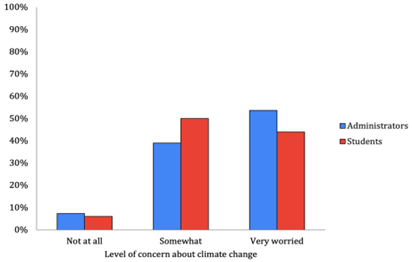

Climate & Education

For administrators, 56% (n = 24) of respondents believed that climate change is caused mainly by human activities, with 10% (n = 4) believing it is from natural environmental changes. When asked about how worried participants are about the effects of global warming, 7% (n = 3) responded not at all, 38% (n = 16) as somewhat worried, and 54% (n = 22) as very worried (Figure 1).

Among students, 90% (n = 58) of respondents identified that climate change is caused mostly by human activities, with 6% (n = 4) indicating they are unsure of its source. When asked how worried participants are about the effects of global warming, 6% (n = 4) responded not at all, 50% (n = 33) as somewhat worried, and 44% (n = 29) as very worried (Figure 1).

Perceptions Around Climate Change

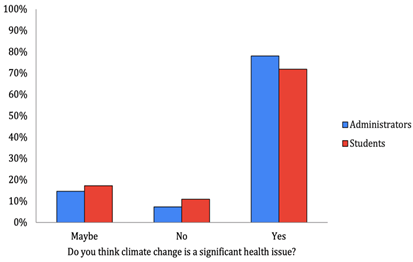

When asked whether or not the respondent believed climate change is a significant health issue, 78% (n = 32) of administrators indicated yes (Figure 2). Regarding the link between health and climate change, 59% (n = 25) of respondents selected that they know enough about it to discuss it casually, 30% (n = 14) said they knew a good amount, and 9% (n = 4) responded that they did not know anything about the link. 76% (n = 33) and 31% (n = 15) of respondents indicated that they have taken measures to rescue greenhouse gas emissions in their personal lives and clinic, respectively.

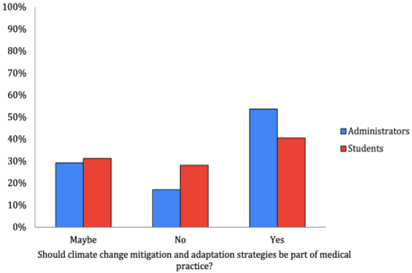

Of administrators, 84% (n = 28) believed climate change will affect health outcomes in their respective practice areas. In terms of the importance of educating patients on climate change, 14% (n = 2) responded with very important, 57% (n = 8) as moderately important, and 29% (n = 4) as not at all important. 21% (n = 3) of participants do not feel confident in explaining climate change to patients. Regarding whether climate change should be a part of medical practice, 52% (n = 22) responded yes, 30% (n = 12) as maybe, and 17% (n = 7) as no (Figure 3). When asked if climate change should be incorporated into medical school curricula, as opposed to medical practice, 53% (n = 16) responded yes, 44% (n = 17) with maybe, and 13% (n = 5) with no.

In the student cohort, 72% (n = 47) indicated that they believe climate change is a significant health issue (Figure 2), with the majority attributing these changes to human activities (90%, n = 60). The majority of respondents, at 72% (n = 47), said they know enough about the link between climate change and health to discuss it casually, with 12% (n = 8) knowing a good amount and 15% (n = 10) not knowing anything about the link. 53% (n = 36) of participants indicated that they have taken measures to rescue greenhouse gas emissions in their personal lives.

63% (n = 40) of student respondents believe climate change will impact health outcomes in their future practice area. With regard to discussing climate change-related topics with patients, 12% (n = 8) said it was very important, 51% (n = 33) selected moderately important, and 36% (n = 23) said it was not important at all. When asked if climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies should be part of medical practice, 41% (n = 26) responded as yes, 31% (n = 20) as maybe, and 28% (n = 18) as no (Figure 3). A subsequent question about whether or not climate change should be integrated more into the medical curricula yielded response rates of 41% (n = 26), 31% (n = 20), and 28% (n = 17) as yes, maybe, and no, respectively.

Facilitators and Barriers

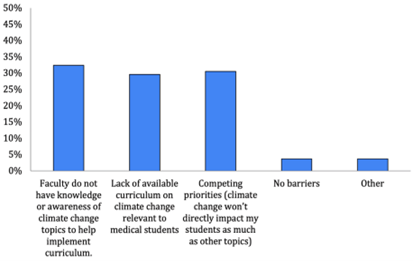

The top 3 most cited topics that administrators and student participants deemed worthy of adding to the curriculum were the effects of climate on health (heat stroke, asthma), natural disasters and access, and the impact of healthcare on the environment. When asked about the most significant barriers to implementing changes to the curriculum, the top 3 reasons were that competing interests exist (students will be impacted by other topics more than climate change), lack of available curriculum on climate change relevant to medical students, and that administrators do not have knowledge or awareness of climate change topics (Figure 4).

Students were given the opportunity to indicate which resources they would find most helpful for learning more about the health impacts of climate change. 25% (n = 27) of respondents selected a dedicated intersection as the most useful resource. Intersessions are month-long electives offered at MSU CHM to first- and second-year students, and they correspond to specific topics. Slides integrated into lectures and dedicated lectures were also identified as helpful resources by 21% (n = 22) and 18% (n = 19) of students, respectively.

Differences Between Administrators and Students

In comparing these two groups, two questions resulted in statistically significant differences in the following two questions: “Have you taken measures to avoid greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) in your life?” (p = 0.02) and “Should climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies be a part of medical practice?” (p < 0.001). While the majority in both groups selected that they have taken measures to avoid greenhouse gas emissions, 22% (n = 15) of student respondents said they have not and do not plan on doing so compared to 35% (n = 15) of administrators. 10% (n = 7) and 11% (n = 5) selected no but said they plan on doing so, and 13% (n = 9) and 21% (n = 9) said they did not know in the student and administrator cohorts, respectively.

More significant variability existed in the administrators’ responses about whether or not climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies should be part of medical practice. 52% (n = 22) of respondents indicated yes, 31% (n = 13) indicated maybe, and 17% (n = 7) said no. Student responses to this question demonstrated 41% (n = 26) yes, 31% (n = 20) maybe, and 28% (n = 18) no. All other questions mentioned in the surveys had no statistically significant differences between these two groups.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study reveal alignment in perspectives between administrators and students regarding the importance of climate change education within medical curricula at a single institution. Despite the diversity in demographic backgrounds, namely age and professional experience, there is a mutual acknowledgement of climate change as a critical issue that intersects with healthcare.

Irrespective of their role within the medical school, most respondents recognize the necessity of equipping healthcare professionals with the knowledge to mitigate the health consequences of climate change. However, there was a significant difference between student and administrator perceptions of the causes of climate change, with significantly more students attributing climate change to human-related causes (90% vs. 56%, p < 0.5). This was also lower than the general population in West Michigan according to the 2023 climate change survey conducted by Yale Climate Opinion Maps (2023).

Nevertheless, administrators are more likely than students to agree that climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies should be integrated into medical practice and curricula (53% vs. 41%, p < 0.5). This collective viewpoint emphasizes the necessity of incorporating climate change education into the medical curriculum. Numerous studies have corroborated these findings (Rabin et al., 2020; Wellbery et al., 2018). For example, Maxwell and Blashki (2016) argue for the inclusion of climate change in medical education to prepare students for clinical practice in a changing climate, to promote public health and eco-health literacy, and to strengthen graduate attributes.

Despite recognition from intergovernmental organizations, health associations, and health professions schools regarding the importance of preparing physicians for the health impacts of climate change, medical school curricula have lagged in integrating targeted training on this topic (Wellbery et al., 2018). This disconnect between acknowledgment and implementation is evidenced by a survey conducted by AMA, which found that only half of US-based medical school programs offer education on climate-health (Mallon & Cox, 2022). This gap is likely not due to a lack of awareness of the health impacts of climate change but rather to a range of barriers that impede the integration of climate change education into the medical curriculum (Moretti et al., 2023; Sarfaty et al., 2016). This study corroborates these findings. Although the majority of both administrators and students acknowledge that climate change will affect health outcomes in their future practice areas (85% and 63%, respectively), climate change is not currently included in the institution’s curriculum.

Integrating climate change education into medical curricula faces several significant barriers. One key challenge is the time demanding nature of existing programs, which leaves little room for new topics due to time constraints and competing curricular priorities (Moretti et al., 2023; Sarfaty et al., 2016). Additionally, there is a lack of faculty expertise in climate change and health topics, which hinders the development and delivery of relevant content. Moreover, existing curricular structures and the perceived relevance of climate change to clinical practice create difficulties in finding appropriate entry points for integrating this crucial topic. Results from this study reflected these barriers.

Consequently, overcoming these obstacles necessitates strategic planning, resource allocation, and the cultivation of an institutional culture that values and promotes the inclusion of climate change and health topics in medical education (Genn, 2020; Rybol et al., 2023).

Tailoring educational content that addresses these barriers could foster a deeper understanding of climate change’s health implications (Maxwell & Blashki, 2016). Madden et al. (2020) propose using indicators to measure and monitor the inclusion of climate change and environmental sustainability in health professionals’ education. This approach suggests a strategic shift towards embedding climate change more explicitly in medical training, addressing the need for comprehensive climate and health education to inform diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease across all medical specialties (Maxwell & Blashki, 2016).

Medical students have a unique role in catalyzing climate change education by actively pushing for its incorporation into their curricula and thereby bridging the gap between current educational content and the urgent need for understanding climate-related health impacts (Rabin et al., 2020). Student-driven advocacy and demand for relevant education would not only highlight the importance of climate change in healthcare but also encourage academic institutions to prioritize and integrate climate change topics into medical training. Ultimately, this proactive involvement from students can enhance future healthcare professionals’ preparedness to address the health challenges posed by climate change.

While this study offers valuable insights and lays the groundwork for similar investigations at other institutions, there are several limitations. A notable limitation is the low response rates of 9% for students and 8.4% for administrators, which may not fully represent the diverse viewpoints within the institution and could introduce response bias. The study’s reliance on email distribution for surveys might have contributed to low response rates, potentially skewing the representation of viewpoints on climate education. The study’s focus on a single institution may also not capture the variability in educational priorities and resources available at other medical schools.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, given the emphasis on addressing climate change. Despite these limitations, the study successfully identifies critical areas for developing targeted educational interventions and curriculum modifications.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study highlights the interest among both administrators and students in climate change education and identifies shared concerns and perceived barriers to its integration into medical curricula. These insights provide a valuable foundation for developing targeted educational interventions and curriculum modifications. Addressing the identified barriers and leveraging common interests could significantly enhance the medical community’s capacity to respond to the health challenges posed by climate change.

Author contributions: SS, LL, AK, AC, SA, & HH: conceptualization, methodology; SS & LL: writing - original draft; SS, LL, AK, AC, SA, & HH: writing review & editing; TP: formal analysis; SS & LL: visualization. All authors agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: No funding source is reported for this study.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that the study was deemed exempt by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board due to the following: Research, conducted in established or commonly accepted educational settings, that specifically involves normal educational practices that are not likely to adversely impact students' opportunity to learn required educational content or the assessment of educators who provide instruction. This includes most research on regular and special education instructional strategies, and research on the effectiveness of or the comparison among instructional techniques, curricula, or classroom management methods.

AI statement: The authors stated that there was no use of generative AI or AI-based tools in this project.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Climate Change. (2024). Climate change. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/climate-change

- Finkel, M. L. (2019). A call for action: Integrating climate change into the medical school curriculum. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8, 265-566. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-019-00541-8

- Gamble, J., Balbus, J., Berger, M., Bouye, K., Campbell, V., Chief, K., Conlon, K., Crimmins, A., Flanagan, B., Gonzalez-Maddux, C., Hallisey, E., Hutchins, S., Jantarasami, L., Khoury, S., Kiefer, M., Kolling, J., Lynn, K., Manangan, A., McDonald, M. … Wolkin, A. (2016). Populations of concern. In The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States (pp. 247-286). Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/J0Q81B0T

- Genn, J. M. (2001). AMEE medical education guide no. 23 (part 1): Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—A unifying perspective. Medical Teacher, 23(4), 337-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590120063330

- Haines, A., & Patz, J. A. (2004). Health effects of climate change. JAMA, 291(1), 99-103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.1.99

- Kotcher, J., Maibach, E., Miller, J., et al. (2021). Views of health professionals on climate change and health: A multinational survey study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(5), e316-e323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00053-X

- Kreslake, J. M., Sarfaty, M., Roser-Renouf, C., Leiserowitz, A. A., & Maibach, E. W. (2018). The critical roles of health professionals in climate change prevention and preparedness. American Journal of Public Health, 108(Suppl 2), S68-S69. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304044

- Lenzen, M., Malik, A., Li, M., Fry, J., Weisz, H., Pichler, P.-P., Chaves, L. S. M., Capon, A., & Pencheon, D. (2020). The environmental footprint of health care: A global assessment. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(7), e271-e279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30121-2

- Madden, D. L., McLean, M., Brennan, M., & Moore, A. (2020). Why use indicators to measure and monitor the inclusion of climate change and environmental sustainability in health professions’ education? Medical Teacher, 42(10), 1119-1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1795106

- Mallon, B., & Cox, N. (2022). Climate action in academic medicine: An overview of how medical schools, teaching hospitals, and health systems are responding to climate change. Association of American Medical Colleges.

- Maxwell, J., & Blashki, G. (2016). Teaching about climate change in medical education: An opportunity. Journal of Public Health Research, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2016.673

- Moretti, K., Rublee, C., Robison, L., Aluisio, A., Marin, B. G., McMurry, T., & Sudhir, A. (2023). Attitudes of US emergency medicine program directors towards the integration of climate change and sustainability in emergency medicine residency curricula. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 9, Article 100199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2022.100199

- Müller, F., Skok, J. I., Arnetz, J. E., Bouthillier, M. J., & Holman, H. T. (2023). Primary care clinicians’ attitude, knowledge, and willingness to address climate change in shared decision-making. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. Advance, 37(1), 25-34. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2023.230027R1

- Rabin, B. M., Laney, E. B., & Philipsborn, R. P. (2020). The unique role of medical students in catalyzing climate change education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520957653

- Rocque, R. J., Beaudoin, C., Ndjaboue, R., Cameron, L., Poirier-Bergeron, L., Poulin-Rheault, R. A., Fallon, C., Tricco, A. C., & Witteman, H. O. (2021). Health effects of climate change: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 11(6), Article e046333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

- Rybol, L., Nieder, J., Amelung, D., et al. (2023). Integrating climate change and health topics into the medical curriculum: A quantitative needs assessment of medical students at Heidelberg University in Germany. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 40(3), Article Doc36. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001618

- Salam, A., Wireko, A. A., Jiffry, R., Ng, J., Patel, H., Zahid, M. J., Mehta, A., Huang, H., Abdul-Rahman, T., & Isık, A. (2023). The impact of natural disasters on healthcare and surgical services in low- and middle-income countries. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 85(8), 3774-3777. https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000001041

- Sarfaty, M., Kreslake, J., Ewart, G., Guidotti, T. L., Thurston, G. D., Balmes, J. R., & Maibach, E. W. (2016). Survey of international members of the American Thoracic Society on climate change and health. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(10), 1808-1813.

- Silverwood, S. M., Lichter, K. E., Stavropoulos, K., Pham, T., Mohamad, O., Golden, D. W., & Braunstein, S. (2024). Assessing the readiness for climate change education in radiation oncology in the United States and Canada. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, 119(4), Article e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2024.04.057

- Wellbery, C., Sheffield, P., Timmireddy, K., Sarfaty, M., Teherani, A., & Fallar, R. (2018). It’s time for medical schools to introduce climate change into their curricula. Academic Medicine, 93(12), 1774-1777. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002368

- Yale Climate Opinion Maps. (2023). Yale program on climate change communication. Yale. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/

- Zeleňáková, M., Purcz, P., Hlavatá, H., & Blišťan, P. (2015). Climate change in urban versus rural areas. Procedia Engineering, 119, 1171-1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.968

How to cite this article

APA

Silverwood, S., Lewis, L., Kim, A., Chang, A., Pham, T., Ashmead, S., & Holman, H. (2026). Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

Vancouver

Silverwood S, Lewis L, Kim A, Chang A, Pham T, Ashmead S, et al. Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1):e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

AMA

Silverwood S, Lewis L, Kim A, et al. Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan. INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED. 2026;22(1), e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

Chicago

Silverwood, Sierra, Lena Lewis, Andrew Kim, Aaron Chang, Tyler Pham, Steven Ashmead, and Harland Holman. "Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2026 22 no. 1 (2026): e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

Harvard

Silverwood, S., Lewis, L., Kim, A., Chang, A., Pham, T., Ashmead, S., and Holman, H. (2026). Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 22(1), e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

MLA

Silverwood, Sierra et al. "Evaluating interest and feasibility of climate education at a medical school in Michigan". Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2026, e2607. https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17805

Full Text (PDF)

Full Text (PDF)