Abstract

The primary objective of this study is to explore the relationship between religiosity and the acceptance of the theory of evolution (ToE) among Greek primary school teachers. A total of 282 in-service primary teachers participated by completing a questionnaire including two scales: the measure of acceptance of the theory of evolution (MATE) and the religiosity scale. Exploratory factor analysis revealed two distinct constructs: religiosity and acceptance of the ToE. The findings indicate a significant negative correlation between these two variables. Specifically, teachers with higher levels of religiosity tend to demonstrate lower acceptance of evolutionary theory, whereas those with lower religiosity are more inclined to embrace it. Notably, while most teachers (66.31%) exhibited high to very high acceptance of evolution, a substantial minority (33.69%) expressed moderate to very low acceptance, underscoring persistent attitudinal divides. These findings have important implications for science education in Greece, where addressing the influence of teachers’ religious beliefs is crucial to supporting the effective teaching of evolution in the classroom.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Type: Research Article

INTERDISCIP J ENV SCI ED, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2026, Article No: e2608

https://doi.org/10.29333/ijese/17806

Publication date: 27 Jan 2026

Article Views: 346

Article Downloads: 295

Open Access HTML Content Download XML References How to cite this articleHTML Content

INTRODUCTION

Scientific literacy is a multifaceted concept encompassing key elements such as scientific reasoning, problem-solving skills, and the ability to generate creative and innovative ideas (Costa et al., 2021). Hence, such a framework empowers people to espouse sophisticated attitudes in their life course (Tuttle et al., 2023). Research has shown that young children’s early science involvement can help them to develop scientific literacy and argumentation skills while, for instance, exploring evolutionary concepts such as adaptation and speciation and recognizing shared patterns of multiple organisms and life processes (Chanet & Lusignan, 2008; Nadelson et al., 2009).

Given that primary education lays the groundwork for future learning, primary teachers play a pivotal role in shaping how scientific theories are introduced. If educators hold reservations or misconceptions about theory of evolution (ToE), they may limit its classroom presence, thereby narrowing students’ exposure to critical scientific frameworks (Griffith & Brem, 2004; Berkman & Plutzer, 2010). Teachers’ scientific understanding and personal beliefs are thus central to promoting–or impeding–evolution instruction (Athanasiou & Stasinakis, 2016; Karataş, 2019).

International research has explored how religiosity affects evolution education, especially in contexts influenced by Protestant and Catholic traditions (Aini et al., 2024; Barnes et al., 2017; Kuschmierz et al., 2020). However, there is limited research examining Orthodox Christian settings–such as Greece–where religious and cultural norms may present unique challenges to science teaching (Charles & Clement, 2018; Pew Research Center, 2018a). Also, most of the relevant studies explore views of either pre-service or in-service teachers of secondary education, failing to explore perspectives of in-service primary school teachers (Athanasiou & Stasinakis, 2016; Barumen et al., 2024; Cofré et al., 2017; Deniz et al., 2007; Glaze et al., 2015; Govender, 2017; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002; Schulteis, 2010). Hence, this study attempts to fill an observed void in contemporary academic discourse about the intersection of science education and religion in Greece by exploring the relationship between the acceptance of ToE and religiosity among primary school teachers and to further understand whether these religious attitudes or other demographics (like gender) influence their scientific beliefs.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Theories of Evolution and Their Importance in Education

What is evolution?

The American Institute of Biological Sciences argues that ToE is the only theory that explains living entities’ origins, evolution, and diversity (Sloane et al., 2023). It is regarded as one of the most preeminent intellectual achievements in modern thought, enumerated alongside other colossal scientific breakthroughs, such as the theory of relativity or calculus (Ruse & Travis, 2009; Urry et al., 2020). According to Charles Darwin, species evolve across time through natural selection, influenced by diversity, heredity, and differential reproductive success (Cabej, 2011). Throughout this process, every hereditary aspect of an organism–whether related to anatomy or behavior–that exhibits the potential of influencing the organism’s fitness compared to other individuals of its kind tends to show signs of increased prevalence in future generations in the same population (Fleagle, 2013). An organism’s traits that offer the ability to maximize its biological fitness under certain environmental conditions will radiate across its population and will be in action as adaptive traits of prospective descendants (Smelser & Baltes, 2001).

Understanding vs. accepting

Given that teachers’ beliefs can influence their willingness to teach evolution, it is important to clarify a key conceptual distinction that underpins much of this discussion. In this context, understanding refers to a cognitive grasp of mechanisms such as natural selection and genetic variation, while acceptance reflects the endorsement of this theory as a valid scientific explanation (Aini et al., 2024). Whereas understanding is grounded in scientific knowledge, acceptance is often shaped by religious or cultural beliefs (Nadelson & Sinatra, 2009). Research shows these constructs do not always align as individuals may understand evolution yet still reject it due to worldview conflicts (Nadelson & Sinatra, 2009; Smith, 2010).

Teaching evolution in school contexts

In his influential essay entitled “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution,” Dobzhansky (1973) claims that evolution is the core process behind diversity and unity of life. This is possible due to elucidating the established connections between anatomy, ecology, and genetics (Dobzhansky, 1973). Hence, the comprehension and acceptance of this theory are of paramount importance because it explains the way species survive and adapt to their environment while explicating biological differences and adaptive changes observed in natural environments, which can be employed in various scientific fields (Hanisch & EIrdosh, 2020). This exploitation can be valuable in cases of handling worldwide problems (i.e., sustainability issues, wildlife preservation, and global climate change) and provide key insights to research efforts for incurable diseases (i.e., cancer) since their growth patterns follow the footsteps of evolutionary mechanisms that have sculpted the natural world (Kreher & McManus, 2023).

Since ToE has a substantial impact on the world, delivering its concepts in the classroom trenches is an indispensable course of action (Barnes et al., 2021). However, an immense amount of the population, even many of those engaged in postsecondary science education, lack a fundamental understanding of ToE (Gregory, 2009). Challenges of teaching ToE is a threefold issue that pertains to

-

comprehending the interconnections among cognitive, religious, epistemological, and affective factors regarding public’s views on ToE,

-

devising, enacting, and evaluating relevant curriculum practices that will reflect current understanding on the matter, and

-

mitigating negative views on ToE (Nehm & Schonfeld, 2007).

The first challenge is establishing connections between concepts across various subjects as it fosters a more holistic approach to comprehending complex themes (Greenwood, 2013; Mård & Klausen, 2023). Yet, the integration of this concept across the curriculum requires a wide range of content knowledge, which can be enhanced by implementing relevant modules in pre-service teachers’ studies (Hanisch & Eirdosh, 2023; Siani & Yarden, 2021).

The second challenge is to create teaching strategies about ToE that can enhance curiosity, through early introduction, active learning, and interdisciplinary connections while nurturing a deeper understanding of science (Nadelson et al., 2009). Such an approach can spark young students’ interest in scientific inquiry as they are becoming increasingly competent in recognizing and exploring patterns while making complex themes more enjoyable and accessible, ipso facto, fueling interest and curiosity regarding the subject at hand (Martínez-Agüero & Hernández, 2023). Furthermore, students’ curiosity is enhanced through interdisciplinary engagement, as they can connect various fields (geology, biology, public health, and beyond) and, thus, discover the relevance of ToE in diverse contexts of everyday life (Hanisch & EIrdosh, 2020). All the above can be carried out effectively after exploring teacher’s views on ToE (Tuttle et al., 2023).

A third persistent challenge in evolution education–closely tied to both curriculum design and teacher preparedness–is the prevalence of misconceptions. These misconceptions, along with the cognitive and sociocultural factors that sustain them, are addressed later.

Educational community perspectives on evolution

Since evolution is considered the substructure of science and modern biology, investigating related attitudes and perceptions of students and teachers can influence the need to promote scientific education in schools while developing suitable educational programs (Tuttle et al., 2023). Comprehending and accepting ToE is a key aspect of teaching this matter effectively (Akyol et al., 2012). However, teachers hesitate to impart ToE within schools (Bertka et al., 2019; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002; Tolman et al., 2021). This reluctance stems from potential conflicts associated with such topics, contradictions with the religious beliefs of students, as well as counterarguments with their perspectives and the challenges teachers may face in their attempt to navigate through such situations effectively (Barnes et al., 2017; Brownell et al., 2013; Southerland & Scharmann, 2013). Many teachers believe that ToE is too controversial/sensitive for classroom discussions and may lead to broader conflict and polarized views (Newall & Reiss, 2023; Reiss, 2019). However, Reiss (2019) argues that ToE–as a well-established theory–cannot be deemed as controversial as it stands alongside other groundbreaking scientific theories (i.e., quantum dynamics, plate tectonics, and periodic table). Thus, recognizing and understanding students’ concerns about ToE while developing proper learning material could reduce students’ perceived conflict between religion and ToE, decreasing tension and enhancing comprehension of historical and modern views of the matter’s cultural context (Bertka et al., 2019).

When pre-service teachers gain widened knowledge of the matter through university courses related to ToE, they display higher acceptance rates than those who have not taken such courses (Karataş, 2019; Kreher & McManus, 2023). Ipso facto, limited knowledge relevant to ToE may lead to a dogmatic rejection or a simplification of the matter’s complexity, labeling it solely as a “change” (Karataş, 2019).

In Serbia, Stanisavljevic et al. (2013) compared comprehension and acceptance of ToE among kindergarten and primary school teachers, biology, physics, and chemistry. Stanisavljevic et al. (2013) discovered that biology teachers show higher comprehension and acceptance of this theory compared to other teachers’ categories. Stanisavljevic et al. (2013) also found a positive correlation between the factors of comprehension and acceptance in all teacher categories. In another study surveying 552 high school biology teachers, Rutledge and Mitchell (2002) found that 43% of the participants avoided or mentioned evolution only briefly in their biology classes due to a lack of understanding or religious beliefs. Similarly, Nehm and Schonfeld (2002) highlight that even teachers with bachelor’s degrees in biology may still have relevant misconceptions, which can be dismantled through targeted and well-developed interventions. Other findings highlight the need for professional development programs in the area, as many educators do not feel competent enough to teach ToE or do not see how this concept can be embodied as an important aspect of the curriculum (Lucero et al., 2019; Nedelson & Nedelson, 2009; Nadelson & Sinatra, 2009).

Additionally, a study in Turkey among in-service biology and science teachers in primary and secondary schools revealed that even though they acknowledge the need for teaching ToE, they often find it difficult to accept the validity of this theory, potentially affecting their ability to teach this topic effectively (Tekkaya et al., 2012). Schulteis (2010) reports that most US biology teachers in private high schools bring evolutionary concepts into the classroom. However, a considerable number (59.2%) believe that scientific evidence does not corroborate relevant concepts. Barumen et al. (2024) also explored perceptions of ToE among private high school biology teachers, revealing their tendency to have lower acceptance of ToE compared to their public-school counterparts. One interesting finding of this study is that teachers in both sectors have lower acceptance rates of the validity of ToE concerning the other four major scientific theories (Barumen et al., 2024).

In Greece, Athanasiou and Papadopoulou (2015) compared studies investigating acceptance factors of ToE among Greek and Turkish university students aspiring to become teachers. They found that both studies correlate with comprehension factors and ToE acceptance (Athanasiou & Papadopoulou, 2015). Furthermore, geologists teaching natural sciences in middle and high school have higher acceptance rates (Athanasiou & Papadopoulou, 2015). According to other data, this finding highlights that geological knowledge provides compelling evidence that fosters the comprehension and acceptance of ToE among teachers and students (Athanasiou et al., 2016). Mantelas and Mavrikaki (2020) found that biology university students (and future middle and high school teachers) display high acceptance rates of the respective theory, higher than those of equivalent samples in the USA and Turkey. Moreover, the findings of this study show that attending a semester course related to evolutionary biology seems to affect the acceptance of ToE (Mantelas & Mavrikaki, 2020). Having explored theoretical, instructional, and attitudinal dimensions of evolution education, the next section turns into a major obstacle in classroom practice: widespread misconceptions and public scepticism.

Misconceptions and Controversies in Evolution Education

A key challenge in evolution education involves addressing persistent misconceptions and negative perceptions surrounding the theory. Despite the countless ways science spans everyday life, a remarkable section of the population voices its skepticism and doubts about widely accepted scientific theories. It even rejects scientifically proven facts like the safety of vaccines, anthropogenic causes of climate change, invasive species, Big Bang theory, or ToE (Borgerding & Dagestan, 2018; Christonasis et al., 2023). This scepticism partly emerges from the human’s conditioned tendency to favor intuitive theories, an assortment of ingrained causal laws and concepts that people embrace to understand, interpret, and predict specific phenomena they experience (Mahr & Csibra, 2021). These theories suggest that they help people navigate life, yet they fail to align with scientific concepts and can lead to misconceptions (Coley & Tanner, 2012; Kelemen, 2019; Vosniadou, 2019).

In a recent systematic review examining 56 studies conducted in 29 European countries during 2010-2020, Kuschmierz et al. (2020) concluded that the power that lies within misconceptions is omnipresent throughout every educational level. Hence, when teachers avoid bringing evolutionary concepts into primary school classrooms, they fail to confront intuitive and deep-rooted misconceptions, thus affecting later students’ ability to understand relevant knowledge thoroughly, leading to a superficial comprehension of ToE (Prinou et al., 2011). Furthermore, education policymakers often underestimate the cognitive capabilities of young children. Research has shown that even 9-year-old students can cognitively grasp the notion of evolution and natural selection successfully (Kenyon et al., 2019). Even kindergarten students can have accurate ideas about certain evolutionary concepts, such as variation, with few already manifesting relevant advanced ideas (Adler et al., 2024).

In Greek primary schools, students are familiar only with specific ToE concepts, such as the adaptive ability of plants and animals in their habitats (Prinou et al., 2011; Stasinakis & Kampourakis, 2018). In secondary education, the coverage of ToE is still greatly limited in matters of available teaching time (Stasinakis & Kampourakis, 2018). Also, introducing ToE in secondary education is deemed a belated procedure because at that time it is already late for students to acquire a coherent conceptual understanding of the matter (Kelemen, 2019). Further to this, researchers have pointed out that scientific misconceptions are shaped during early school years, between 5-7 years of age (Adler et al., 2024; Kelemen, 2019; Potvin & Cyr, 2017; Smolleck & Hershberger, 2011). During this period, children develop their first cognitive structures through everyday interactions and intuitive interpretations, often opposed directly to scientific explanations (Vosniadou, 2019; Vosniadou & Brewer, 1992). In the absence of ToE from primary school curricula, those misconceptions can be solidified and carried through secondary and upper education levels despite the presence of a more sophisticated level of scientific expertise (Carey, 1985; Foster, 2012; Kelemen, 2019; Potvin & Cyr, 2017; Vosniadou, 2019); even after the introduction of teaching scientifically proven facts that contradict them (Posner et al., 1982).

To address these persistent misconceptions, contemporary evolution education frameworks offer valuable insights. For example, the conceptual ecology model emphasizes how individuals’ acceptance of evolution is shaped by an interconnected web of prior knowledge, personal beliefs, and sociocultural influences (Athanasiou et al., 2016). Additionally, models of conceptual change and cognitive reconstruction highlight the motivational and epistemic challenges learners face when replacing intuitive ideas with scientifically accurate ones (Sinatra & Mason, 2013). Embedding these frameworks into evolution education can help explain why misconceptions persist and inform more effective strategies for promoting conceptual understanding.

Additionally, gender has been identified as a contributing sociocultural factor in shaping misconceptions and attitudes toward evolution. Research indicates that women, particularly within religious contexts, tend to exhibit lower acceptance rates of evolution compared to men (Großschedl et al., 2014; Kim & Nehm, 2010; Peker et al., 2010). Although this gender gap has narrowed over the last three decades (Miller et al., 2021), such differences suggest that cultural narratives, identity development, and epistemic trust may influence how individuals process and respond to scientific explanations (Baker, 2013; Nadelson et al., 2014). Understanding how gender intersects with other sociocultural variables can provide additional insight into the persistence of evolution-related misconceptions and inform more inclusive educational interventions.

Religiosity and Evolution Acceptance

Religiosity and education

The relationship between ToE and religious beliefs has been a long-standing subject of significant dispute. The research argues that students’ perceived conflict between ToE and religion is a robust predictor of their acceptance of the said theory, even stronger than religiosity (Barnes et al., 2021; Glaze et al., 2015). Other findings suggest that religiosity and specific religious denominations are critical factors in fathoming individuals’ attitudes toward ToE (Gutowski et al., 2023).

Although defining religion has been challenging among scholars, it is perceived as an assemblage of beliefs and respective practices (Casey, 2021). At this point, three relevant terms require further explanation: religious beliefs, affiliation, and religiosity. First, religious beliefs have two main characteristics; on the one hand, they are defined by a strong faith in superior entities–impersonal forces or anthropomorphic gods–and their interactions with humans. On the other hand, such beliefs involve a strict moral code regarding hierarchical structures and divine principles (Engstrom & Laurin, 2020). Second, religious affiliation is one’s membership or connection to a specific organized religious community or group, thus, one’s religious identity, encompassing religious traditions and/or denomination (Campbell, 2005). Third, religiosity refers to one’s inclination to affiliate with varying religious beliefs and commitment to corresponding principles and activities (Ellis et al., 2019). In educational settings, religiosity is considered a salient identity trait leading to religious practice engagement, potentially influencing perceptions of the scientific explanations behind aspects of everyday life (Barnes et al., 2017; McPhetres & Zuckerman, 2018). Stated otherwise, religiosity pertains to the depths of personal faith and its influence on daily life (Ellis et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2019).

Research has shown that higher levels of religiosity are connected to a likelihood of perceived conflict between religious faith and ToE (Barnes et al., 2022). Studies on teachers and students from diverse religious settings expose a typical association between higher levels of religiosity and lower acceptance rates of ToE, even in understanding evolutionary concepts (Aini et al., 2024). Furthermore, research has revealed that higher rates of religiosity, whether evaluated as overall devotion to religious practices, biblical literalism, or church attendance, are broadly linked with lower rates of acceptance of ToE (Baker, 2013; Barone et al., 2014; Colburn & Henriques, 2006; Hill, 2014; Manwaring et al., 2018).

Religious contexts and cross-cultural perspectives on evolution acceptance

Numerous studies highlight how religious tradition and cultural context influence perceptions of evolution education. In the USA, Evangelical Christian beliefs have been strongly associated with resistance to teaching evolution in schools (Aini et al., 2024; Barnes et al., 2017; Berkman & Plutzer, 2010; Borgerding & Dagistan, 2018). Similar patterns have been observed in European countries, where religious affiliation and church attendance correlate with lower acceptance of evolution (Gutowski et al., 2023; Newall & Reiss, 2023; Konnemann et al., 2018; Kuschmierz et al., 2020). In Islamic-majority societies across South Asia and the Middle East, religious teachings often conflict with evolutionary theory, presenting further instructional and ideological challenges (Dagher & Boujaoude, 1997; Deniz et al., 2017; Karataş, 2019; Tekkaya et al., 2012). Despite these developments, limited scholarly attention has been directed toward Orthodox Christian contexts. This represents a significant gap, as the theological and cultural dimensions of Orthodoxy–such as those found in Greece–may exert unique influences on science education, potentially differing from those in Protestant and Catholic settings (Charles & Clement, 2018; Pew Research Center, 2018b; Stanisavljevic et al., 2013).

Intersection of ToE and religion

The intersection of ToE and religion is a multidimensional theme, and whether it relates to a conflict or integration discourse depends vastly on scientific understanding, religious interpretations, and cultural context. The most common perceived interplay between those two realms is one of conflict, specifically in religious traditions adhering to creationism or biblical literalism. Creationism is the religious belief that life and the universe were created ab initio by a supreme divine entity (Moore, 2000) and is often mistakenly perceived as an alternative to ToE (Arold, 2024; Watts & Kutschera, 2021). Biblical literalism is the conviction that the Bible is a scientific text that includes solid information about the origin of the world, and as such, it should be interpreted literally (Berkman & Plutzer, 2010). This literal interpretation may lead individuals to directly reject ToE because they believe that acceptance of ToE translates to rejecting one’s own belief in God (Barnes et al., 2020). This conflict is evident in opposing discourses about teaching ToE in schools, where scientific curricula collide with religious beliefs (Plutzer et al., 2020). Furthermore, a diversified argument under the name intelligent design challenges the validity of ToE, claiming that specific features of living entities are best interpreted under the prism of intelligent interference rather than unguided natural processes (Ruse, 2007). The chain of reasoning behind this argument is that some characteristics of organisms are too complex to come into being through normal processes and thus demand the interference of a designer who took time to think of them and put them later into place (Forrest & Gross, 2004). An alternative to this is theistic evolution, which advocates that evolutionary processes do, indeed, happen, but they are directed by God’s hand (Ayala, 2007; Pennock, 2003).

Intelligent design and theistic evolution are considered as an attempt from religious environments to reconcile religion and science (Brigandt, 2013). Even though science and religion are two different realms, research has revealed that an approach based on reconciliatory terms in theology and biology courses has led to increased levels of ToE acceptance without a diminishing effect on students’ religiosity (Tolman et al., 2020). Once people understand that religion and science are shaped through different epistemologies and are related to distinct domains, they will then be able to accept ToE without the sense of rejecting their religious beliefs (Sinatra & Nadelson, 2011).

The Greek Orthodox Context

The Greek Orthodox religion is a dominant feature of Greek society, molding individuals’ social identity while shaping their opinions toward historical, political, cultural, societal, scientific, or educational issues (Sakellariou, 2022). Since the birth of the Greek State in 1830, the Orthodox Church declared itself as the “mother of the nation”, becoming the mechanism used by governmental forces to establish and propagate an indispensable national identity in the aftermath of centuries of Ottoman occupation (Beaton, 2021). The inseparable nature of the relationship between nation and religion is reflected in the Greek constitution, where the Eastern Orthodox Church of Christ is acknowledged as the prevailing religion of the country under the section entitled “Relations of church and state” (Hellenic Parliament, 2022). The Orthodox church exerts a strong political influence and, despite recurring attempts to segregate church and state, their institutional relations are kept robust and powerful (Bakas, 2024).

Religion is intertwined with the Greek identity, as 75% of the population shares the belief that being a Christian Orthodox is essential for one’s own Greekness (Pew Research Center, 2018a). Furthermore, 90% of the population identify themselves as Orthodox Christians (Pew Research Center, 2018a), while 53% of Greeks share the notion of a linkage between morality and faith in God (Pew Research Center, 2020). A strong religious affiliation–and the subsequently expressed religiosity–is frequently connected with more conservative opinions toward a range of issues, potentially leading to stronger adherence to traditional attitudes and behaviors, potentially resulting in oppositional stances regarding scientific issues that are perceived to collide with traditional values (Lee, 2022; Sherkat, 2017; Williams et al., 2013), such ToE for interpreting the origin of life (Aini et al., 2024; Barnes et al., 2021; Barone et al., 2014; Gutowski et al., 2023; Hill, 2014; McPhetres & Zuckerman, 2018; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002).

Study Objective and Research Questions

Given the gaps and trends identified in the literature, the objective of this study is to explore the relationship between religiosity and the acceptance of the ToE among Greek primary school teachers (GPST) guided by the following research questions:

-

What is the level of acceptance of ToE among in-service primary school teachers in Greece?

-

What is the religiosity level of in-service primary school teachers in Greece?

-

Is there a statistically significant relation between acceptance of the ToE and religiosity?

-

To what degree does religiosity predict the level of acceptance of ToE?

-

Are there gender-related differences in the acceptance of ToE?

METHODOLOGY

Participants

This study was conducted during the academic year 2022-2023 and enlisted the participation of 282 in-service primary teachers, with a gender distribution of 212 women and 68 men. Employing a convenient sampling method, the sample constituted a diverse representation of teachers from schools within the Regional Unit of Ioannina. Participants were primarily teaching in mainstream general education settings, with no differentiation by school type collected beyond this general classification.

Instrument

All participants completed a three-part questionnaire. The first segment gathered data on demographic characteristics such as gender. The second section employed the measure of acceptance of theory of evolution (MATE), developed by Rutledge and Warden (1999). This scale is designed to assess a participant’s view on the acceptance or rejection of ToE. It comprises 20 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (= 1) to strongly agree (= 5). In the third segment, the centrality of religiosity scale (CRS), developed by Huber and Huber (2012), was employed. Additionally, five more questions proposed by Mantelas and Mavrikaki (2020) were integrated into CRS. These items were selected to enrich the assessment of religious ideology and experience–two CSR dimensions particularly relevant in Orthodox educational settings–by reflecting beliefs about scriptural literalism and early religious socialization. Their inclusion aligns with the CRS’s multidimensional framework (Huber & Huber, 2012). The adapted scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .97), supporting the psychometric robustness of the modified instrument. Both segments have previously undergone rigorous assessment for reliability and validity reasons within the Greek population (Athanasiou & Papadopoulou, 2015; Athanasiou et al., 2012, 2016; Mantelas & Mavrikaki 2020). Table 1 outlines the dimensions of MATE and religiosity scale while Table 2 categorizes participants according to their scores in both scales.

Table 1. Dimensions of MATE and religiosity scales

|

Table 2. Participants’ categorization scores at MATE and religiosity scales

|

The MATE and religiosity scales underwent translation into Greek, followed by a back-translation process to ensure content or conceptual equivalence, in accordance with the international test commission guidelines for test adaptation (Beaton et al., 2000; Hambleton, 2001). Two bilingual speakers translated the items from the English versions into Greek, and another two bilingual speakers performed the back-translation in English. This process revealed minor translation discrepancies, leading to slight adjustments in vocabulary. Furthermore, a panel of researchers and experts familiar with the literature and the research area thoroughly examined each scale item to establish face validity, content validity, and cultural appropriateness. Following this review, minor wording adaptations of certain items were implemented (Stylos et al., 2021).

Pilot Study

A pilot study with 20 teachers from the target population was conducted to assess the translated questionnaire for clarity, linguistic appropriateness, conceptual accuracy, and completion time. Participants required approximately 10-15 minutes to complete it. Minor issues were identified, addressed, and the revised instrument was subsequently administered to the main study sample.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses utilized the IBM SPSS 26.0 statistical package and Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheets. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was employed to validate the goodness of fit of the questionnaire. Initially, all negatively formulated items were re-coded by reversing the scores (1 = 5, 2 = 4, 3 = 3, 4 = 2, 5 = 1). Subsequently, a principal component analysis (PCA) with orthogonal rotation (Varimax rotation) determined correlations between the variables (Field, 2018). Factors displaying structure coefficients of .30 or higher were considered significant and employed for the interpretation process of the factors.

Additionally, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test (> .70) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity confirmed sampling adequacy. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α, and regression analysis was conducted to examine the influence of predictors such as gender and religiosity.

RESULTS

EFA

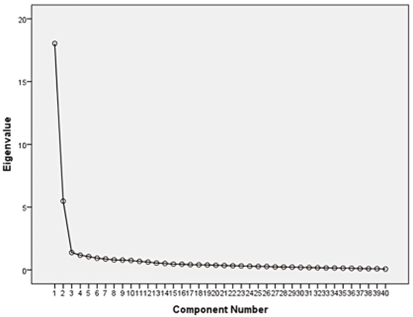

A PCA with orthogonal rotation (Varimax rotation) was conducted on the 40 items comprising the questionnaire. The KMO was .959 and the Barlett’s test of sphericity was found to be statistically significant (χ2 [780] = 9,871.900, p < .001), affirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Although five factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, only two were retained based on the scree plot, which revealed a clear inflection after the second factor, suggesting a two-factor solution (Figure 1).

This decision was also supported by theoretical interpretability and factor loadings, as only two factors aligned meaningfully with the constructs of religiosity and evolution acceptance. These two factors explained 58.79% of the variance.

The items were sequenced according to their factor loading (from highest to lowest) and grouped according to each factor. Table 3 shows the factor loadings after rotation. The items loaded in the first factor (N = 20) represent the Religiosity scale and explained 45.07% of the variance. Items of the second factor (N=20) represent the Acceptance of ToE and explained 13.69% of the variance.

Table 3. Summary of questionnaire items and their factor loadings

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reliability Analysis

The Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient for both factors resulted from EFA was found to be 0.95 and 0.97 for MATE and religiosity scale, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Number of items, a-Cronbach and % of total variance of the questionnaire

|

Acceptance of ToE

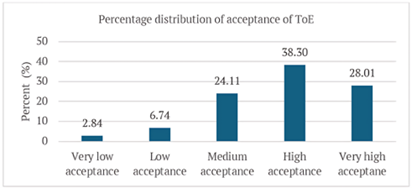

The next phase involved the evaluation of the acceptance of ToE. The participants’ mean score on the MATE scale was 80.25 ± 12.07%. According to the results (Figure 2), 38.30% of the GPST participating in this study exhibited a high acceptance of ToE, while 28.01% demonstrated very high acceptance. In contrast, 33.69% exhibited medium to very low levels of acceptance toward this theory.

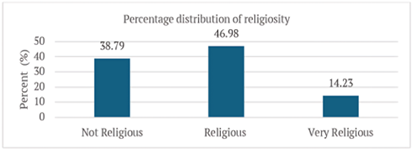

Religiosity

On the religiosity scale, the mean score participants obtained was 51.23 ± 21.59%. According to the results (Figure 3), 61.21% of the GPST participating in the study were identified as religious, while 38.79% were categorized as non-religious.

Regression Analysis

The correlation between religiosity and acceptance of ToE was negative and statistically significant (r = -0.541, p < .001), indicating that higher religiosity is associated with lower acceptance of ToE. To further explore this relationship, a multiple linear regression was performed with gender and religiosity as predictors and MATE scores as the dependent variable.

The analysis revealed a multiple correlation of R = .544, suggesting a moderate overall relationship between the predictors and evolution acceptance. The model explained 29.6% of the variance in MATE scores (R² = .296). Religiosity was a statistically significant negative predictor (b = -0.298, t = -10.593, p < .001), reinforcing the inverse relationship between religious commitment and evolution acceptance.

The regression coefficient for gender (B = 2.219) indicated a slight positive association with MATE scores, but this effect was not statistically significant (t = 1.568, p = .118). Therefore, gender was not a meaningful predictor in this model (Table 5).

Table 5. Regression analysis with MATE as the dependent variable and gender and religiosity as independent variables

|

DISCUSSION

The present study delves into the intricate relationship between the acceptance of ToE and religiosity among teachers in Greek primary schools, revealing that while a majority of GPSTs (66.31%) highly or very highly accept ToE (research question 1, RQ1), a substantial minority (33.69%) report moderate to very low acceptance, suggesting persistent ideological and pedagogical tensions within science education–a pattern also observed in international contexts (Ferguson et al., 2024; Glaze et al., 2015; Newall & Reiss, 2023; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002; Short & Hawley, 2015; Tolman et al., 2021).

Additionally, religiosity ranges from medium to high levels among in-service GPST (RQ2). Moreover, 61.21% of the participants identified themselves as “religious”. This aligns with broader findings that strong religious identity is often associated with hesitancy toward evolution (Baker, 2013; Barone et al., 2014; Colburn & Henriques, 2006; Hill, 2014; Manwaring et al., 2018). The rest (38.79%) identified as non-religious, meaning that either they do not have a religious affiliation, or they adhere to religious practices at lower levels compared to the majority’s tendencies. This distribution reflects the strong presence of religion among GPST, pointing to emerging challenges about personal belief conflicts when teaching scientific concepts, such as ToE (Kaloi et al., 2022).

The findings signify the negatively correlated relationship between the acceptance of ToE and religiosity within Orthodox Christianity (RQ3). These results echo earlier findings in other contexts, where a lower level of acceptance is often predicted by strong religious convictions and the subsequent expressed religiosity (Aini et al., 2024; Baker, 2013; Barone et al., 2014; Colburn & Henriques, 2006; Gutowski et al., 2023; Hill, 2014; Manwaring et al., 2018; McPhetres & Zuckerman, 2018; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002), specifically in cultures where religion is an integral part of the society, as the case in Greece (European Commission, 2005; Pew Research Center, 2020). However, this research underlines the diversified reality of the Greek Orthodox Church as its doctrine slightly differentiates from other Christian denominations, offering a more flexible route of allegoric interpretation of the book of Genesis (Gregersen, 2013; Palantza, 2014; Pentiuc, 2014). Scholars such as Origen and Basil the Great have been cited to support this hermeneutic approach (Palantza, 2014; Pentiuc, 2014). This view may hold the key to understanding the reason behind the moderate acceptance of ToE observed among GPST, as they strive to balance deeply rooted religious beliefs with scientific concepts. In fact, regarding the statement whether ‘Historical’, factual elements of the Old Testament (mostly chronologies, the way that earth, plants, animals, humans were created, cataclysm, etc.) are mostly realistic and not symbolic, the majority’s response (67.37%) reflects the preferred symbolical interpretation of the Bible endorsed by the Greek Orthodox Church.

Furthermore, the framework of non-overlapping magisteria proposed by Gould (2002) may offer a useful conceptual lens to interpret the observed variation in the acceptance of ToE. According to this model, science and religion occupy distinct domains of inquiry: science addresses empirical facts, while religion is concerned with moral and existential values. When individuals recognize that these two realms rely on different epistemologies, they may become more receptive to scientific explanations–such as ToE–without perceiving a threat to their religious beliefs (Sinatra & Nadelson, 2011). This perspective may help explain why a considerable portion of GPST demonstrate moderate to high levels of ToE acceptance, even in the context of strong religious and cultural traditions.

Moreover, religiosity emerged as a moderate yet meaningful negative predictor of the acceptance of ToE, acknowledging the inversive character that defines the relationship of these two variables (RQ4). When an increased level of religiosity is present, a decrease in ToE acceptance follows, a finding that aligns with past reports revealed that religiosity may forge cultural or cognitive barriers in accepting ToE (Barnes et al., 2020, 2021). The nature of this relationship suggests the need to imply culturally competent approaches capable of building bridges between religious and scientific perspectives. Educators may cultivate teaching environments that acknowledge and respect religious diversity while providing the necessary framework for scientific understanding by confronting perceived conflicts through targeted educational material. Importantly, the regression model yielded an R² value of 0.296, indicating that religiosity and the selected demographic variables explain approximately 29.6% of the variance in ToE acceptance. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, this represents a moderate effect size, underscoring that while religiosity plays a meaningful role, other unmeasured factors–such as epistemic cognition, evolution knowledge, and pedagogical experience–also contribute to shaping attitudes toward evolution (Aini et al., 2024; Baker, 2013; Barone et al., 2014; Colburn & Henriques, 2006; Gutowski et al., 2023; Hill, 2014; Manwaring et al., 2018; McPhetres & Zuckerman, 2018; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002; Weisberg et al., 2018).

Finally, and in contrast to prior studies (Großschedl et al., 2014; Kim & Nehm, 2010; Peker et al., 2010), gender did not emerge as a significant predictor of ToE acceptance in the present study. This finding suggests that religiosity may exert a stronger influence than gender on shaping attitudes toward evolution among GPST (RQ5). Notably, this result aligns with broader international trends showing a diminishing gender gap in attitudes toward scientific concepts over the past three decades (Miller et al., 2021). It is therefore plausible that sociocultural factors or individual belief systems now play a more prominent role than gender alone in influencing perspectives on evolution.

CONCLUSION

The present study’s findings reflect global patterns of ToE observed in relevant settings. Interestingly, the religious tradition of Greek Orthodox Christianity, with its diverse interpretation of Holy Scripture, appears to fabric a unique background where a considerable portion of primary school teachers exhibit a moderate to high level of ToE acceptance, underlying an inclination to acknowledge and respect religious convictions without diminishing scientific accuracy in the process. Exploring primary school teachers’ attitudes toward ToE underlines the need to introduce the teaching of this theory as early as possible while promoting the development of courses and resources for teacher education programs that thoroughly address the ToE but also give tailored guidelines regarding the implementation of effective teaching methods, especially in environments where scientific theories may oppose personal or religious convictions.

The Greek Orthodox Church often interferes in educational contexts and strongly promotes its opinions, as is reflected in an appeal by Church Officials in 2016 to the State Council regarding their opposition to the introduction of revised school textbooks for the curriculum subject “Religious Education”. The appeal was vindicated by the State Council and the decision by the Ministry of Education regarding the introduction of the said textbooks was negated by the Supreme Administrative Court of Greece (Sakellariou, 2022). This firm religious presence in matters of the state creates a social and educational reality where educators are challenged to balance between religious and cultural values and scientific knowledge, ensuring that everyone’s concerns are being addressed without inflicting damage on the delivery of scientific accuracy. Hence, this study aims to address an incessant gap in understanding how in-service primary school teachers perceive and deliver ToE, specifically in backgrounds where religious/cultural beliefs may be opposed to scientific knowledge, as teachers can largely influence their students’ understanding and acceptance of scientific issues (Brickhouse, 1990).

Views and attitudes of in-service primary school teachers toward ToE in relation to religiosity put forward a broad range of standpoints that do not smoothly align with a framework of cooperation or conflict. This reflects the wider historical discourse between religion and science, where, as Livingstone (2003) argues, diminishing this relationship to a narrative of heroes against villains turns a blind eye to cultural and rhetorical subtle differences. Future education strategies should consider the diverse possible routes in which scientific understanding can exist alongside religious beliefs, specifically in teaching endeavors related to ToE, by showing the distinctive nature of religion and science as two different realms shaped by different epistemologies.

Limitations & Future Direction

A core limitation of the present study concerns the sampling strategy. The participants were recruited through convenience sampling from a specific region of Greece, which may constrain the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. As such, the results may not fully capture the diversity of views held by primary school teachers across the entire country. Future research should aim to include a more geographically and demographically diverse sample, ideally using randomized sampling methods, to enable more comprehensive and generalizable conclusions about Greek teachers’ attitudes toward the ToE. Additionally, the study did not collect data on participants’ years of teaching experience, which may limit interpretations regarding how professional seniority relates to attitudes toward the ToE.

Another limitation is that data were collected only through quantitative methods. The absence of qualitative methods can negatively impact the findings, as this approach can enhance the understanding of deeper personal and cultural reasons behind one’s perceptions (Zohrabi, 2013). Additionally, as the study relied on self-report questionnaires, there is a possibility of social desirability bias influencing responses, particularly given the sensitive nature of religiosity and evolution-related beliefs. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences and limits the ability to assess changes over time. Thus, future researchers may find it beneficial to incorporate such approaches when collecting relevant data.

While the present study focused on religiosity and gender as predictors of evolution acceptance, it is important to acknowledge additional variables that have consistently shown strong explanatory power in international literature. Factors such as evolution knowledge, understanding of the nature of science, epistemic cognition, and prior exposure to formal evolution instruction have been found to significantly influence evolution acceptance and may attenuate the effects of religiosity (Aini et al., 2024; Baker, 2013; Barone et al., 2014; Colburn & Henriques, 2006; Gutowski et al., 2023; Hill, 2014; Manwaring et al., 2018; McPhetres & Zuckerman, 2018; Rutledge & Mitchell, 2002; Weisberg et al., 2018). Although these were beyond the scope of the current research design, future studies incorporating these dimensions could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms shaping evolution-related attitudes in the Greek orthodox landscape.

Lastly, this study did not examine other influential factors beyond religiosity and gender, such as scientific knowledge, understanding of evolution or the nature of science, additional demographics, or emotional and social dimensions (Wiles & Alters, 2011). Nevertheless, the findings can inform policy updates and enhancements to primary education programs that support early conceptual development and prevent the entrenchment of misconceptions (Camilli et al., 2010; Klahr et al., 2011; Leuchter et al., 2014; Novak, 2005). They also offer valuable input for designing teacher education resources that address ToE content and pedagogy, especially in belief-challenging contexts. More broadly, the results provide a foundation for policymakers to develop improved curricula and targeted professional development promoting early evolution instruction. Finally, the authors suggest future research involves a professional development intervention for primary teachers focused on ToE content and pedagogy, to assess shifts in teacher attitudes and instructional effectiveness.

Author contributions: GS, EG, TC, AK, & KK: contributed equally to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, resources, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. All authors agreed with the results and conclusions.

Funding: No funding source is reported for this study.

Ethical statement: The authors stated that ethical approval was not required for this study according to national and institutional regulations, as the research involved non-invasive educational procedures and the anonymous collection of data from adult participants. No sensitive or personally identifiable information was collected. Participation in the study was voluntary. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research, the procedures involved, and their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The authors further stated that, to ensure confidentiality, no names, identification numbers, or other personal identifiers were collected. All data were stored securely and used exclusively for research purposes.

AI statement: The authors stated that the manuscript made use of AI-based tools (ChatGPT and Grammarly) to assist in enhancing grammar, fluency, and clarity during writing. All content, interpretations, and conclusions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Data sharing statement: Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Adler, I. K., Fiedler, D., & Harms, U. (2024). About birds and bees, snails and trees: Children’s ideas on animal and plant evolution. Science Education, 188(5), 1356-1391. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21873

- Aini, R. Q., Stewart, M., Brownell, S. E., & Barnes, M. E. (2024). Exploring patterns of evolution acceptance, evolution understanding, and religiosity among college biology students in the United States. Evolution Education and Outreach, 17, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-024-00207-y

- Akyol, G., Tekkaya, C., & Sungur, S. (2010). The contribution of understandings of evolutionary theory and nature of science to pre-service science teachers’ acceptance of evolutionary theory. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1889-1893. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2010.12.419

- Akyol, G., Tekkaya, C., Sungur, S., & Traynor, A. (2012). Modeling the interrelationships among pre-service science teachers’ understanding and acceptance of evolution, their views on nature of science and self-efficacy beliefs regarding teaching evolution. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 23(8), 937-957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-012-9296-x

- Arold, B. W. (2024). Evolution vs. creationism in the classroom: The lasting effects of science education. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 139(4), 2331-2375. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae019

- Athanasiou, K., & Papadopoulou, P. (2015). Evolution theory teaching and learning: What conclusions can we get from comparisons of teachers’ and students’ conceptual ecologies in Greece and Turkey? Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 11(4), 841-853. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2015.1443a

- Athanasiou, K., & Stasinakis, P. K. (2016). Investigating Greek biology teachers’ attitudes towards evolution teaching with respect to their pedagogical content knowledge: Suggestions for their professional development. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 12(6), 1605-1617. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2016.1249a

- Athanasiou, K., Katakos, E., & Papadopoulou, P. (2012). Conceptual ecology of evolution acceptance among Greek education students: The contribution of knowledge increase. Journal of Biological Education, 46(4), 234-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2012.716780

- Athanasiou, K., Katakos, E., & Papadopoulou, P. (2016). Acceptance of evolution as one of the factors structuring the conceptual ecology of the evolution theory of Greek secondary school teachers. Evolution, 9, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-016-0058-7

- Ayala, F. J. (2007). Darwin’s gift to science and religion. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11732

- Bakas, I. T. (2024). The Greek Orthodox Church: A unique cultural and social environment. In R. Darques, G. Sidiropoulos, & K. Kalabokidis (Eds.), The geography of Greece. World regional geography book series (pp. 67-77). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29819-6_5

- Baker, J. O. (2013). Acceptance of evolution and support for teaching creationism in public schools: The conditional impact of educational attainment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52(1), 216-228. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12007

- Barnes, M. E., Dunlop, H. M., Sinatra, G. M., Hendrix, T. M., Zheng, Y., & Brownell, S. E. (2020). “Accepting evolution means you can’t believe in God”: Atheistic perceptions of evolution among college biology students. CBE–Life Sciences Education, 19(2), Article ar21. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-05-0106

- Barnes, M. E., Elser, J., & Brownell, S. E. (2017). Impact of a short evolution module on students’ perceived conflict between religion and evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 79(2), 104-111. https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2017.79.2.104

- Barnes, M. E., Riley, R., Bowen, C., Cala, J., & Brownell, S. E. (2022). Community college student understanding and perceptions of evolution. CBE–Life Sciences Education, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-09-0229

- Barnes, M. E., Supriya, K., Zheng, Y., Roberts, J. A., & Brownell, S. E. (2021). A new measure of students’ perceived conflict between evolution and religion (PCoRE) is a stronger predictor of evolution acceptance than understanding or religiosity. CBE–Life Sciences Education, 20(3), Article ar42. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-02-0024

- Barone, L. M., Petto, A. J., & Campbell, B. C. (2014). Predictors of evolution acceptance in a museum population. Evolution Education and Outreach, 7, Article 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-014-0023-2

- Beaton, R. (2021). Greece: Biography of a modern nation. University of Chicago Press.

- Berkman, M. B., Pacheco, J. S., & Plutzer, E. (2008). Evolution and creationism in America’s classrooms: A national portrait. PLoS Biology, 6(5), Article e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060124

- Berkman, M., & Plutzer, E. (2010). The battle for America’s classrooms. In M. Berkman, & E. Plutzer (Eds.), Evolution creationism and the battle to control America’s classroom (pp. 215-228). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511760914.010

- Berti, A. E., Barbetta, V., & Toneatti, L. (2015). Third-graders’ conceptions about the origin of species before and after instruction: An exploratory study. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(2), 215-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9679-5

- Bertka, C. M., Pobiner, B., Beardsley, P., & Watson, W. A. (2019). Acknowledging students’ concerns about evolution: A proactive teaching strategy. Evolution Education and Outreach, 12, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-019-0095-0

- Borgerding, L. A., & Dagistan, M. (2018). Preservice science teachers’ concerns and approaches for teaching socioscientific and controversial issues. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 29(4), 283-306. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2018.1440860

- Brickhouse, N. W. (1990). Teachers’ beliefs about the nature of science and their relationship to classroom practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248719004100307

- Brigandt, I. (2013). Intelligent design and the nature of science: Philosophical and pedagogical points. In K. Kampourakis (Ed.), The philosophy of biology. History, philosophy and theory of the life sciences, vol 1 (pp. 205-238). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6537-5_11

- Brownell, S. E., Price, J. V., & Steinman, L. (2013). Science communication to the general public: Why we need to teach undergraduate and graduate students this skill as part of their formal scientific training. The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 12(1), E6-E10.

- Cabej, N. R. (2011). Epigenetic principles of evolution. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-415831-3.00003-3

- Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S., & Barnett, W. S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teachers College Record the Voice of Scholarship in Education, 112(3), 579-620. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811011200303

- Campbell, D. E. (2005). Religious affiliation and commitment, measurement of. In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social measurement (pp. 367-375). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-12-369398-5/00485-0

- Carey, S. (1985). Conceptual change in childhood. MIT Press.

- Casey, P. J. (2021). Religion, definition of. In The encyclopedia of philosophy of religion (pp. 1-7). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119009924.eopr0330

- Chanet, B., & Lusignan, F. (2008). Teaching evolution in primary schools: An example in French classrooms. Evolution Education and Outreach, 2(1), 136-140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0095-y

- Charles, F., & Clement, P. (2018). Russian teacher’s conceptions of evolution. International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 5(4), 377-384.

- Christonasis, A., Stylos, G., Chatzimitakos, T., Kasouni, A., & Kotsis, K. T. (2023). Religiosity and teachers’ acceptance of the Big Bang Theory. Eurasian Journal of Science and Environmental Education, 3(1), 25-32. https://doi.org/10.30935/ejsee/13043

- Cofré, H., Cuevas, E., & Becerra, B. (2017). The relationship between biology teachers’ understanding of the nature of science and the understanding and acceptance of the theory of evolution. International Journal of Science Education, 39(16), 2243-2260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2017.1373410

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Colburn, A., & Henriques, L. (2006). Clergy views on evolution, creationism, science, and religion. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 43(4), 419-442. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20109

- Coley, J. D., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Common origins of diverse misconceptions: Cognitive principles and the development of biology thinking. CBE–Life Sciences Education, 11(3), 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-06-0074

- Costa, A., Loureiro, M., & Ferreira, M. E. (2021). Scientific literacy: The conceptual framework prevailing over the first decade of the twenty-first century. Revista Colombiana De Educación, (81), 195-228. https://doi.org/10.17227/rce.num81-10293

- Dagher, Z., & Boujaoude, S. (1997). Scientific views and religious beliefs of college students: The case of biological evolution. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34, 429-445. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199705)34:5<429::AID-TEA2>3.0.CO;2-S

- Deniz, H., Donnelly, L. A., & Yilmaz, I. (2007). Exploring the factors related to acceptance of evolutionary theory among Turkish preservice biology teachers: Toward a more informative conceptual ecology for biological evolution. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(4), 420-443. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20223

- Dobzhansky, D. (1973). Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 35(3), 125-129. https://doi.org/10.2307/4444260

- Ellis, L., Farrington, D. P., & Hoskin, A. W. (2019). Institutional factors. In L. Ellis, D. P. Farrington, & A. W. Hoskin (Eds.), Handbook of crime correlates (pp. 105-162). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804417-9.00003-X

- Engstrom, H. R., & Laurin, K. (2020). Existential uncertainty and religion. In K. A. Vail, & C. Routledge (Eds.), The science of religion, spirituality, and existentialism (pp. 243-259). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-817204-9.00018-4

- European Commission. (2005). Special eurobarometer 225/wave 63.1: Social values, science & technology. European Commission. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/448

- Ferguson, D. G., Larsen, R. A., Bailey, E. G., & Jensen, J. L. (2024). Predicting evolution acceptance among religious students using the predictive factors of evolution acceptance and reconciliation (pFEAR) instrument. Evolution Education and Outreach, 17, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-024-00201-4

- Fleagle, J. G. (2013). Adaptation, evolution, and systematics. In J. G. Fleagle (Ed.), Primate adaptation and evolution (pp. 1-7). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-378632-6.00001-x

- Forrest, B., & Gross, P. R. (2004). Creationism’s trojan horse: The wedge of intelligent design. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195157420.001.0001

- Foster, C. (2012). Creationism as a misconception: Socio-cognitive conflict in the teaching of evolution. International Journal of Science Education, 34, 2171-2180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2012.692102

- Glaze, A. L., Goldston, M. J., & Dantzler, J. (2014). Evolution in the southeastern USA: Factors influencing acceptance and rejection in pre-service science teachers. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 13(6), 1189-1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-014-9541-1

- Gould, S. J. (2002). Rocks of ages: Science and religion in the fullness of life. National Geographic Books.

- Govender, N. (2017). Physical sciences preservice teachers’ religious and scientific views regarding the origin of the universe and life. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(2), 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9695-5

- Greenwood, R. (2013). Subject-based and cross-curricular approaches within the revised primary curriculum in Northern Ireland: Teachers’ concerns and preferred approaches. Education 3-13, 41(4), 443-458. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.819618

- Gregersen, N. H. (2013). Evolutionary theology. In A. L. C. Runehov, & L. Oviedo (Eds.), Encyclopedia of sciences and religions (pp. 809-817). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_406

- Gregory, T. R. (2009). Understanding natural selection: Essential concepts and common misconceptions. Evolution Education and Outreach, 2(2), 156-175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-009-0128-1

- Griffith, J. A., & Brem, S. K. (2004). Teaching evolutionary biology: Pressures, stress, and coping. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(8), 791-809. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20027

- Großschedl, J., Konnemann, C., & Basel, N. (2014). Pre-service biology teachers’ acceptance of evolution: The influence of the educational background, knowledge, and beliefs. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 7, Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-014-0018-z

- Gutowski, R., Aptyka, H., & Großschedl, J. (2023). An exploratory study on students’ denominations, personal religious faith, knowledge about, and acceptance of evolution. Evolution Education and Outreach, 16, Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-023-00187-5

- Hanisch, S., & EIrdosh, D. (2020). Conceptual clarification of evolution as an interdisciplinary science. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/vr4t5

- Hanisch, S., & Eirdosh, D. (2023). Developing teacher competencies for teaching evolution across the primary school curriculum: A design study of a pre-service teacher education module. Education Sciences, 13(8), Article 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080797

- Hellenic Parliament. (2022). The constitution of Greece. Hellenic Parliament. https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/UserFiles/f3c70a23-7696-49db-9148-f24dce6a27c8/THE%20CONSTITUTION%20OF%20GREECE.pdf

- Hill, J. P. (2014). Rejecting evolution: The role of religion, education, and social networks. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(3), 575-594. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12127

- Huber, S., & Huber, O. W. (2012). The centrality of religiosity scale (CRS). Religions, 3(3), 710-724. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3030710

- Jensen, J. L., Manwaring, K. F., Gill, R. A., Sudweeks, R. S., Davies, R. S., Olsen, J. A., Phillips, A. J., & Bybee, S. M. (2019). Religious affiliation and religiosity and their impact on scientific beliefs in the United States. BioScience, 69(4), 292-304. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz014

- Kaloi, M., Hopper, J. D., Hubble, G., Niu, M. E., Shumway, S. G., Tolman, E. R., & Jensen, J. L. (2022). Exploring the relationship between science, religion & attitudes toward evolution education. The American Biology Teacher, 84(2), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2022.84.2.75

- Karataş, A. (2019). Opinions of pre-service teachers about evolution. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 7(8). https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v7i8.4284

- Kelemen, D. (2019). The magic of mechanism: Explanation-based instruction on counterintuitive concepts in early childhood. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14, 510-522. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619827011

- Kenyon, L. O., Walter, E. M., & Romine, W. L. (2019). Transforming a college biology course to engage students: Exploring shifts in evolution knowledge and mechanistic reasoning. In U. Harms, & M. Reiss (Eds.), Evolution education re-considered (pp. 249-269). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14698-6_14

- Kim, S. Y., & Nehm, R. H. (2010). A cross-cultural comparison of Korean and American science teachers’ views of evolution and the nature of science. International Journal of Science Education, 33(2), 197-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690903563819

- Klahr, D., Zimmerman, C., & Jirout, J. (2011). Educational interventions to advance children’s scientific thinking. Science, 333(6045), 971-975. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204528

- Konnemann, C., Höger, C., Asshoff, R., Hammann, M., & Rieß, W. (2018). A role for epistemic insight in attitude and belief change? Lessons from a cross-curricular course on evolution and creation. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1187-1204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9783-y

- Kreher, S. A., & McManus, E. (2023). An interdisciplinary course on evolution and sustainability increases acceptance of evolutionary theory and increases understanding of interdisciplinary application of evolutionary theory. Evolution, 16, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-023-00188-4

- Kuschmierz, P., Meneganzin, A., Pinxten, R., Pievani, T., Cvetković, D., Mavrikaki, E., Graf, D., & Beniermann, A. (2020). Towards common ground in measuring acceptance of evolution and knowledge about evolution across Europe: A systematic review of the state of research. Evolution Education and Outreach, 13, Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-020-00132-w

- Lee, J. J. (2022). Religious exclusivism and mass beliefs about the religion v. science debate: A cross-national study. International Journal of Sociology, 52(3), 229-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2022.2055288

- Leuchter, M., Saalbach, H., & Hardy, I. (2014). Designing science learning in the first years of schooling. An intervention study with sequenced learning material on the topic of ‘floating and sinking’. International Journal of Science Education, 36(10), 1751-1771. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2013.878482

- Livingstone, D. N. (2003). Re-placing Darwinism and Christianity. In D. C. Lindberg, & R. L. Numbers (Eds.), When science and Christianity meet (pp. 183-202). University of Chicago Press.

- Lombrozo, T., Thanukos, A., & Weisberg, M. (2008). The importance of understanding the nature of science for accepting evolution. Evolution Education and Outreach, 1(3), 290-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0061-8

- Lucero, M. M., Delgado, C., & Green, K. (2019). Elucidating high school biology teachers’ knowledge of students’ conceptions regarding natural selection. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(6), 1041-1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-019-10008-1

- Mahr, J. B., & Csibra, G. (2021). A short history of theories of intuitive theories. In J. Gervain, G. Csibra, & K. Kovács (Eds.), A life in cognition: Studies in cognitive science in honor of Csaba Pléh (pp. 219-232). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66175-5_16

- Mantelas, N., & Mavrikaki, E. (2020). Religiosity and students’ acceptance of evolution. International Journal of Science Education, 42(18), 3071-3092. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1851066

- Manwaring, K. F., Jensen, J. L., Gill, R. A., Sudweeks, R. R., Davies, R. S., & Bybee, S. M. (2018). Scientific reasoning ability does not predict scientific views on evolution among religious individuals. Evolution Education and Outreach, 11, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-018-0076-8

- Mård, N., & Klausen, S. H. (2023). Speaking and thinking about crosscurricular teaching. In S. H. Klausen, & N. Mård (Eds.), Developing a didactic framework across and beyond school subjects (pp. 7-18). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003367260-3

- Martínez-Agüero, M., & Hernández, C. (2023). The evolution of teaching evolution. Education and New Developments, 2, 102-106. https://doi.org/10.36315/2023v2end021

- McPhetres, J., & Zuckerman, M. (2018). Religiosity predicts negative attitudes towards science and lower levels of science literacy. PLoS ONE, 13(11), Article e0207125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207125

- Miller, J. D., Scott, E. C., Ackerman, M. S., Laspra, B., Branch, G., Polino, C., & Huffaker, J. S. (2021). Public acceptance of evolution in the United States, 1985-2020. Public Understanding of Science, 31(2), 223-238. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625211035919

- Moore, R. (2000). The revival of creationism in the United States. Journal of Biological Education, 35(1), 17-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2000.9655730

- Nadelson, L. S., & Nadelson, S. (2009). K-8 educators perceptions and preparedness for teaching evolution topics. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21(7), 843-858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-009-9171-6

- Nadelson, L. S., & Sinatra, G. M. (2009). Educational professionals’ knowledge and acceptance of evolution. Evolutionary Psychology, 7(4), 490-516. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470490900700401

- Nadelson, L., Culp, R., Bunn, S., Burkhart, R., Shetlar, R., Nixon, K., & Waldron, J. (2009). Teaching evolution concepts to early elementary school students. Evolution Education and Outreach, 2(3), 458-473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-009-0148-x

- Nehm, R. H., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2007). Does increasing biology teacher knowledge of evolution and the nature of science lead to greater preference for the teaching of evolution in schools? Journal of Science Teacher Education, 18, 699-723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-007-9062-7

- Newall, E., & Reiss, M. J. (2023). Evolution hesitancy: Challenges and a way forward for teachers and teacher educators. Evolution Education and Outreach, 16, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-023-00183-9

- Novak, J. D. (2005). Results and implications of a 12-year longitudinal study of science concept learning. Research in Science Education, 35(1), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-004-3431-4

- Palantza, A. (2014). The creation narratives in the Western and Greek-Orthodox theology of the 20th century. Review of Ecumenical Studies Sibiu, 6(3), 460-472. https://doi.org/10.2478/ress-2014-0134

- Peker, D., Comert, G. G., & Kence, A. (2010). Three decades of anti-evolution campaign and its results: Turkish undergraduates’ acceptance and understanding of the biological evolution theory. Science & Education, 19, 739-755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-009-9199-1

- Pentiuc, E. J. (2014). The Old Testament in Eastern Orthodox tradition. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195331226.001.0001

- Pew Research Center. (2018a). Eastern and Western Europeans differ on importance of religion, views of minorities, and key social issues. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/

- Pew Research Center. (2018b). Religious belief and national belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/05/CEUP-FULL-REPORT.pdf

- Pew Research Center. (2020). The global God divide. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2020/07/20/the-global-god-divide/

- Plutzer, E., Branch, G., & Reid, A. (2020). Teaching evolution in U.S. public schools: A continuing challenge. Evolution Education and Outreach, 13, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-020-00126-8

- Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211-227. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730660207

- Potvin, P., & Cyr, G. (2017). Toward a durable prevalence of scientific conceptions: Tracking the effects of two interfering misconceptions about buoyancy from preschoolers to science teachers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 54(9), 1121-1142. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21396

- Prinou, L., Halkia, L., & Skordoulis, C. (2011). The inability of primary school to introduce children to the theory of biological evolution. Evolution Education and Outreach, 4(2), 275-285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-011-0323-8

- Reiss, M. J. (2019). Evolution education: Treating evolution as a sensitive rather than a controversial issue. Ethics and Education, 14(3), 351-366. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2019.1617391

- Rosengren, K. S., Brem, S. K., Evans, E. M., & Sinatra, G. M. (2012). Evolution challenges. Itegrating research and practice in teaching and learning about evolution. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199730421.001.0001

- Ruse, M. (2007). Dossier évolution et créationnisme [The evolution and creationism file]. Intelligent design theory. Natures Sciences Sociétés, 15(3), 285-286. https://doi.org/10.1051/nss:2007063

- Ruse, M., & Travis, J. (2009). Evolution: The first four billion years. Harvard University Press.

- Rutledge, M. L., & Mitchell, M. A. (2002). High school biology teachers’ knowledge structure, acceptance & teaching of evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 64(1), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.2307/4451231

- Rutledge, M. L., & Warden, M. A. (1999). The development and validation of the measure of acceptance of the theory of evolution instrument. School Science and Mathematics, 99(1), 13-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.1999.tb17441.x

- Sakellariou, A. (2022). Greek society in transition: Trajectories from Orthodox Christianity to Atheism. In Boundaries of religious freedom: Regulating religion in diverse societies (pp. 129-150). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92395-2_8

- Sherkat, D. E. (2017). Religion, politics, and Americans’ confidence in science. Politics and Religion, 10(1), 137-160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048316000535

- Short, S. D., & Hawley, P. H. (2015). The effects of evolution education: Examining attitudes toward and knowledge of evolution in college courses. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1), 67-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491501300105

- Siani, M., & Yarden, A. (2021). “I think that teachers do not teach evolution because it is complicated”: Difficulties in teaching and learning evolution in Israel. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 20(3), 481-501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-021-10179-w

- Sinatra, G. M., & Nadelson, L. (2011). Science and religion: Ontologically different epistemologies? In R. S. Taylor, & M. Ferrari (Eds.), Epistemology and science education: Understanding the evolution vs. intelligent design controversy (pp. 173-193). Routledge.

- Sloane, J. D., Wheeler, L. B., & Manson, J. S. (2023). Teaching nature of science in introductory biology: Impacts on students’ acceptance of biological evolution. PLoS ONE, 18(8), Article e0289680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289680

- Smelser, N. J., & Baltes, P. B. (2001). International encyclopedia of social & behavioral sciences. Pergamon.

- Smolleck, L., & Hershberger, V. (2011). Playing with science: An investigation of young children’s science conceptions and misconceptions. Current Issues in Education, 14(1).